Samsung has filed its motion [PDF] asking for judgment as a matter of law, a new trial and remittitur pursuant to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 50 and 59. An entire section is blacked out, but there is plenty left, showing in detail how no reasonable jury could find what this jury did. It ends by asking for a new trial in the interests of justice, saying that there was not an even playing field in this trial, with Apple getting lots of breaks that Samsung did not:IX. A NEW TRIAL SHOULD BE GRANTED IN THE INTERESTS OF JUSTICE

Rule 59 permits the Court to grant a new trial to prevent manifest unfairness. Here, the Court's restraints on trial time, witnesses and exhibits (Dkt. 1297, 1329) were unprecedented for a patent case of this complexity and magnitude, and prevented Samsung from presenting a full and fair case in response to Apple's many claims. Denial of Samsung's "empty chair" motion (Dkt. 1692, 1721) compounded the problem, enabling Apple to exploit Samsung's absent witnesses to repeated advantage at trial. RT 3348:14-17; 4080:3-6; 4090:2-4; 4095:7-14; 4232:15-22.

Samsung was also treated unequally: Apple's lay and expert witnesses were allowed to testify "we were ripped off" and "Samsung copied" (RT 509:11-510:22; 659:2-664:19; 1957:15-21; 1960:15-1963:1), while Samsung's witnesses were barred from explaining how Samsung's products differ from Apple's (RT 850-12-851:20; 2511:9-2515:5), or even how one Samsung product differs from another (RT 948:14-950:17). Samsung was required to lay foundation for any Apple document (RT 524:15-525:19; 527:3-12), while Apple was not (RT 1525:12-1526:7; 1406:11-1410:8; 1844:16-1845:8; 987:21-988:20; 2832:6-12). Apple was permitted to play advertisements (RT 641:6-642:16; 645:14-646:7), but Samsung was not (Dkt 1511). And Apple had free rein to cross-examine Samsung's experts based on their depositions, but Samsung did not. RT 1085:6-11; 1188:9-15; 1213:17-1220:5. In the interests of justice, Samsung therefore respectfully requests that the Court grant a new trial enabling adequate time and evenhanded treatment of the parties. There are a lot of other filings, including Apple's equivalent motion [PDF], which asks for the usual sun, moon and stars, plus all the supporting declarations and exhibits, and we are working on getting those for you. Swing back by.

Meanwhile, if anyone can do this Samsung motion as text, I'd appreciate it a lot. It's a tiff.

Yes, Samsung points out that the jury made manifest errors, some of them truly obvious. For just one example, on page 25 of the PDF, Samsung says a new trial is necessary "due to inconsistencies in the jury's verdict on the '915 patent", in that the jury found that the Ace, Intercept and Replenich devices don't infringed the '915 patent but all the other accused devices do. Here's why Samsung says that is a problem:

These verdicts are irreconcilably inconsistent, for the Ace, Intercept and Replenish exhibit the same behavior as devices found to infringe, including the Droid Charge, Indulge, Epic 4G, Infuse 4G, Transform and Prevail. THe same Android version found in the non-infringing Ace (Android 2.2.1) and the Intercept and Replenish (Android 2.2.2) are found in these other devices which the jury found to be infringing. A new trial is therefore warranted under Fed. R. Civ. P. 49. Los Angeles Nut House v. Holiday Hardware Corp., 825 F2d 1351, 1356 (9th Cir. 1987).

I believe the redacted first section may be about jury misconduct, based on the cases cited for pages 2 and 3 (13 and 14 of the PDF). For example, here's United States v. Colombo, where a juror was accused of failing to mention something she should have in voir dire. Here's United States v. Gonzalez, about the right to a trial with unbiased jurors. Here's United States v. Perkins, a case where a media account about jury deliberations resulted in the court holding an evidentiary hearing, in which the jurors were questioned under oath by the judge about the reported irregularities. You can find the L.A. Nut House case

here, a case where the jury was inconsistent in its decisions. And a case cited on page 13 is L & W, Inc. v. Shertech, Inc., which you can find

here, and it too is about a jury coming in with an inconsistent verdict. 'Nuff said about that.

There are many other examples of what Samsung feels are jury mistakes.

The worst example is in the area of damages, where the figures simply make no sense at all. Samsung actually phrases it more tactfully, saying that "the basis for the jury's award is unclear." I'll say. That section begins on page 28 of the PDF.

But it wasn't just the jury that goofed, Samsung says. It was also the court, in that the jury instructions did not properly explain aspects of the law of trade dress, for example, or what is required to establish willfulness (see footnotes 8, 10 and 11).

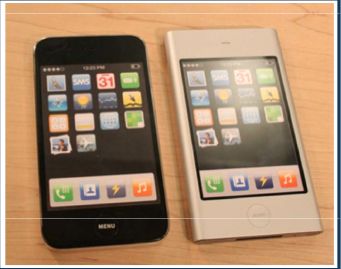

Samsung also says that no rational jury could find Apple's design patents valid. First, they are all functional, Samsung argues, and hence not protectable, there's at least one issue of double patenting, and there is prior art. Ditto with the trade dress claims. If you are wondering what's functional about rounded corners, I would direct you to an exhibit, Exhibit 42 [PDF] to Docket # 1991, an internal Apple email from Richard Howarth to Jonny Ive, dated March 8, 2006. You see two phones, one an iPhone and one "what shin's doing with the sony-style chappy" where Shin was able to "achieve a much smaller-looking product with a much nicer shape to have next to your ear and in your pocket" with "the size and shape/comfort benefits" that were "hard to ignore with a product we have to carry and use all day, every day", compared to the "extrudo shape" Apple was then planning to use. Here's the graphic:

Imagine holding the one on the right up to your ear and missing and jabbing yourself with the pointed corner. Please don't say it couldn't happen. I'm quite capable myself of doing something just that goofy and awkward. P.S. Did Apple invent rounded corners?

Samsung addresses the new trend of seeking patent-like protection from trademarks, and that raises constitutional concerns, in that trademarks are not time-limited like patents:

"The traditional interest in trademark protection is stretched very thin in dilution cases where confusion is absent," as here, and unlike patent protection, which is time-limited, trade dress law poses special dangers if used to give "permanent protection" to "the design of an article of manufacture." I.P. Lund Trading ApS v. Kohler Co., 163 F.3d 27, 53 (1st Cir. 1998) (Boudin, J., concurring).6 These concerns have constitutional dimension.7

__________

6 See Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 U.S. 205, 213 (2000) ("Consumers should not be deprived of the benefits of competition with regard to the utilitarian and aesthetic purposes that product design ordinarily serves."); Anti-Monopoly, Inc. v. Gen. Mills Fun Group, 611 F.2d 296, 301 (9th Cri. 1979) ("trademark is misuses if it serves to limit competition"); Avery Dennison Corp. v. Sumpton, 189 F.3d 868, 875 (9th Cir. 1999) (recognizing breadth of dilution claims). Even in the infringement context, courts reject claims based on alleged post-sale confusion as to product configuration trade dress. Gibson Guitar Corp. v. Paul Reed Guitars, LP, 423 F.3d 539 (6th Cir. 2005).

7 See Bonito Boats, Inc. v. Thunder Craft Boats, Inc., 489 U.S. 141,, 146 (1989) ("Congress may not create patent monopolies of unlimited duration"); Sears v. Stiffel, 376 U.S. 225, 232-33 (1964); Comptco Corp. v. Day-Brite Lighting, Inc., 376 U.S. 234, 237 (1964); I.P. Lund Trading, 163 F.3d at 50 (recognizing constitutional concerns when "attempting to apply the dilution analysis to the design itself of the competing product involved"); Merch. & Evans, Inc. v. Roosevelt Bldg. Products Co., Inc., 963 F.2d 628, 633 (3d Cir. 1992) ("indefinite trademark protection of product innovations would frustrate the purpose of the limited duration of patents"). If this goes to the US Supreme Court, I'll be glad, in that it will be an opportunity for the court to directly address the issue of the spreading of trademark protection into a kind of eternal patent-like level of monopoly.

Here it is as text, minus the headers and table of contents, and cases, which I'll add later, and I'll post pages as they are finished, rather than waiting until it's all done, so you can get started [update: all done]:

***********************

QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP

Charles K. Verhoeven (Cal. Bar No. 170151)

[email]

[address, phone, fax]

Kathleen M. Sullivan (Cal. Bar No. 242261)

[email]

Kevin P.B. Johnson (Cal. Bar No. 177129)

[email]

Victoria F. Maroulis (Cal. Bar No. 202603)

[email]

[address, phone, fax]

Susan R. Estrich (Cal. Bar No. 124009)

[email]

Michael T. Zeller (Cal. Bar No. 196417)

[email]

[address, phone, fax]

Attorneys for SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS

CO., LTD., SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS

AMERICA, INC. and SAMSUNG

TELECOMMUNICATIONS AMERICA, LLC

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA, SAN JOSE DIVISION

APPLE INC., a California corporation,

Plaintiff,

vs.

SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO., LTD., a

Korean business entity; SAMSUNG

ELECTRONICS AMERICA, INC., a New

York corporation; SAMSUNG

TELECOMMUNICATIONS AMERICA,

LLC, a Delaware limited liability company,

Defendants.

____________

CASE NO. 11-cv-01846-LHK

SAMSUNG NOTICE OF MOTION AND

MOTION FOR JUDGMENT AS A

MATTER OF LAW, NEW TRIAL

AND/OR REMITTITUR

PURSUANT TO

FEDERAL RULES OF CIVIL

PROCEDURE 50 AND 59

Date: December 6, 2012

Time: 1:30 p.m.

Place: Courtroom 8, 4th floor

Judge: Hon. Lucy H. Koh

[PUBLIC REDACTED VERSION]

Table of Contents

Page

NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION ........................... 1

MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES ...... ......... 1

I. [REDACTED]............................ ......... 2

II. SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW OR A

NEW TRIAL ON APPLE'S DESIGN PATENT INFRINGEMENT CLAIMS .................. 4

A. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Infringement of Apple's Design Patents ....... 4

B. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Apple's Design Patents Valid .............. 7

III. SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW OR A

NEW TRIAL ON APPLE'S TRADE DRESS CLAIMS .......................... 8

A. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Apple's Trade Dress Protectable ......... 8

B. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Actionable and Willful Dilution ............ 10

IV. SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW OR A

NEW TRIAL ON APPLE'S UTILITY PATENT INFRINGEMENT CLAIMS ............... 12

A. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Apple's Utility Patents Valid .................. 12

B. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Infringement Of Apple's Utility Patents ............. 13

V. THE RECORD LACKS CLEAR AND CONVINCING EVIDENCE OF WILLFUL

INFRINGEMENT .................................................. 15

VI. THE RECORD LACKS SUFFICIENT EVIDENCE OF DIRECT

INFRINGEMENT OR ACTIVELY INDUCED INFRINGEMENT BY SEC ........ ....... 16

VII. SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT, NEW TRIAL AND/OR

REMITTITUR ON DAMAGES ........................ 17

A. The Record Lacks Sufficient Evidence To Support The Damages Verdict ............18

l. The Award Of $948,278,061 For Samsung's Profits .................18

2. The Award of $91,132,279 For Apple's Lost Profits .............. 20

3. The Award Of $9,180,124 In Royalties .................. 22

B. The Damages Rest Upon An Incorrect Notice Date ........................ 23

C. At A Minimum, The Jury's Damages Award Should Be Remitted .......... 24

1. Reduction Of $70,034,295 In Lost Profits.............24

i

2. Reductions of $253,328,000 And $220,952,000 To Reflect Correct

Notice Dates ................................. 25

3. Reductions Of $329,204,825 And $86,162,404 Based On The

Portion Of Samsung's Profits Attributable To Infringement or

Dilution ...................... ....... 25

4. Reduction of $57,867,383 On The Prevail ...................... 26

VII.

SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW ON ITS

OFFENSIVE CASE........................................ 26

A. Judgment of Infringement Should be Entered for the '516 and '941 Patents ......... 26

B. Standards Patents Exhaustion ............................... 28

C. Judgment Should Be Entered For Samsung On The '460, '893, & '711

Patents......................................... 29

IX.

A NEW TRIAL SHOULD BE GRANTED IN THE INTERESTS OF JUSTICE ............. 30

ii

Table of Authorities

Page

Cases

adidas Am., Inc. v. Payless Shoesource, Inc.,

2008 WL 4279812 (D. Or., Sept. 12, 2008) ......... 21, 27

Advanced Display Sys., Inc. v. Kent State Univ.,

212 F.3d 1272 (Fed. Cir. 2000) ........................1

Amsted Indus. Inc. v. Buckeye Steel Castings Co.,

24 F.3d 178 (Fed. Cir. 1994) ...........................24

Anti-Monopoly, Inc. v. Gen. Mills Fun Group,

611 F.2d 296 (9th Cir. 1979) .........................8

Apple Computer, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp.,

35 F.3d 1435 (9th Cir. 1994) ......................6

Aro Mfg. Co. v. Convertible Top Replac. Co.,

377 U.S. 476 (1964) ................................27

Au-Tomotive Gold Inc. v. Volkswagen of Am., Inc.,

457 F.3d 1062 (9th Cir. 2006) ........................8, 9

Avery Dennison Corp. v. Sumpton,

189 F.3d 868 (9th Cir. 1999) .......................8, 10

BIC Leisure Prods., Inc. v. Windsurfing Int'l, Inc.,

1 F.3d 1214 (Fed. Cir. 1993) .............................21

SEB S.A. v. Montgomery Ward & Co.,

594 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2010) ..............29

Bandag, Inc. v. Al Bolser's Tire Stores, Inc.,

750 F.2d 903 (Fed. Cir. 1984) ..........................12

Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc. v. Gore & Assoc., Inc.,

682 F.3d 1003 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ........................15

Bell Commc'ns Res., Inc. v. Vitalink Commc'ns Corp.,

55 F.3d 615 (Fed. Cir. 1995) ............................30

Black & Decker, Inc. v. Robert Bosch Tool Corp.,

260 F. App'x 284 (Fed. Cir. 2008) .......................15

Bonito Boats, Inc. v. Thunder Craft Boats, Inc.,

489 U.S. 141 (1989) ......................................8, 16

Brands Corp. v. Fred Meyer, Inc.,

809 F.2d 1378 (9th Cir. 1987) .............10

iii

Brocklesby v. United States,

767 F.2d 1288 (9th Cir. 1985) ..............25

Bush & Lane Piano Co. v. Becker Bros.,

222 F. 902 (2d Cir. 1915) ..................... 19

Bush & Lane Piano Co. v. Becker Bros.,

234 F. 79 (2d C1r. 1916) .......................... 19

Carbice Corp. of Am. v. Am. Patents Dev. Corp.,

283 U.S. 27 (1931) ............................. 19

Casanas v. Yates,

2010 WL 3987333 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 12, 2010) .................3

Coach Inc. v. Asia Pac. Trading Co.,

676 F. Supp. 2d 914 (C.D. Cal. 2009) ........ ........ 26

CollegeNET, Inc. v. XAP Corp.,

483 F. Supp. 2d 1058 (D. Oregon 2007) ....... ........ 12

Compco Corp. v. Day-Brite Lighting, Inc.,

376 U.S. 234 (1964) ............................. 8

Contessa Food Prods., Inc. v. Conagra, Inc.,

282 F.3d 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2002) ......................... 6

Cornell Univ. v. Hewlett-Packard Co.,,

609 F. Supp. 2d 279 (N.D.N.Y. 2009) ..................... 19, 25

Crystal Semiconductor Corp. v. Tritech Microelecs. Int'l, Inc.,

246 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2001) ....................... ........ 21

DSU Med Corp. v. JMS Co.,

471 F.3d 1293 (Fed. Cir. 2006) ............................ ........ 17

DePuy Spine, Inc. v. Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Inc.,

567 F.3d 1314 (Fed. Cir. 2009) .............................. 16

Disc Golf Ass'n, Inc. v. Champion Discs, Inc.,

158 F.3d 1002 (9th Cir. 1998) ............................... 9

Duraco Prod., Inc. v. Joy Plastic Enter., Ltd.,

40 F.3d 1431 (3d Cir. 1994) .................................. 10

Dyer v. Calderon,

151 F.3d 970 (9th Cir. 1998) ........ .......... 2

Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc.,

543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008) .............. 4, 16

Elmer v. ICC Fab., Inc.,

67 F.3d 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1995) ......................9

iv

Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., Ltd.,

234 F.3d 558 (Fed. Cir. 2000) .............................. 25

In re First Alliance Mortg. Co.,

471 F.3d 977 (9th C1r. 2006) ..................... ........ 17, 25

Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd. v. Jazz Photo Corp.,

394 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2005) ............................ 29

Funai Elec. Co., Ltd. v. Daewoo Elecs. Corp.,

616 F.3d 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2010) ........................... 24

Gibson v. Clanon,

633 F.2d 851 (9th Cir. 1981) ................ 3

Go Med Indus., Ltd. v. Inmed Corp.,

471 F.3d 1264 (Fed. Cir. 2006) .............. 23

Goodyear Tire v. Hercules Tire,

162 F.3d 1113 (Fed. Cir. 1998) ................. 16

Hard v. Burlington N.R.R.,

812 F.2d 482 (9th C1r. 1987) ............................... 2, 3

Highmark, Inc. v. Allcare Health Mgmnt. Sys., Inc.,

687 F.3d 1300 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ............................... 15

Hupp v. Siroflex of Am.,

122 F.3d 1456 (Fed. Cir. 1997) ....... ....... 16

i4i Ltd. P'ship v. Microsoft Corp.,

598 F.3d 831 (Fed. Cir. 2010) ......... ....... 15

I.P. Lund Trading ApS v. Kohler Co.,

163 F.3d 27 (lst C1r. 1998) ................... .......... 8, 10

Informatica Corp. v. Business Objects Data Integration, Inc.,

2007 WL 2344962 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 16, 2007) ....................... 25

Int'l Seaway Corp. v. Walgreens Corp.,

589 F.3d 1233 (Fed. Cir. 2009) .......... ......... 6

Intel Corp. v. Broadcom Corp.,

173 F. Supp. 2d 201 (D. Del. 2001) ................. 29

Interactive Gift Exp., Inc. v. Compuserve Inc.,

256 F.3d 1323 (Fed. C1r. 2001) ..................... ....... 30

Invitrogen Corp. v. Biocrest Mfg., L.P.,

327 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2003) .......... ....... 28

Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc.,

456 U.S. 844 (1982) ....................... .......... 9, 10

v

IpVenture, Inc. v. Cellco P'ship,

2011 WL 207978 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 21, 2011) ................. 15

Jazz Photo Corp. v. US.,

439 F.3d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2006) ...................... 29

Jessen Elec. & Serv. Co. v. Gen. Tel. Co.,

106 F.3d 407 (9th Cir. 1997) ......................... 1

Junker v. HDC Corp.,

2008 WL 3385819 (N.D. Cal. July 28, 2008) ......... ........ 19

Kellogg Co. v. Nat'l Biscuit Co.,

305 U.S. 111 (1938) ............................... ........ 10

LML Holdings, Inc. v. Pac. Coast Dist., Inc.,

2012 WL 1965878 (N.D. Cal. May 30, 2012) ......... ........ 15

L&W, Inc. v. Shertech, Inc.,

471 F.3d 1311 (Fed. Cir. 2006) ....... ........ 13

Lakeside-Scott v. Multnomah Cty.,

556 F.3d 797 (9th Cir. 2009) ............... ....... 1

Laserdynamics v. Quanta Computer, Inc.,

_ F.3d __, 2012 WL 3758093 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 30, 2012) ......... ........ 10

Lee v. Dayton-Hudson,

838 F.2d 1186 (Fed. Cir. 1988) ....... ....... 4

Lindy Pen Co. v. Bic Pen Corp.,

982 F.2d 1400 (9th Cir. 1993) ............. ........ 20

Litecubes, LLC v. N. Light Products, Inc.,

523 F.3d 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2008) ..............29

Litton Sys., Inc. v. Honeywell, Inc.,

140 F.3d 1449 (Fed. Cir. 1998) ............................ ........ 24

Los Angeles Nut House v. Holiday Hardware Corp.,

825 F.2d 1351 (9th Cir. 1987) ........................,........ ........ 14

Lotus Dev. v. Borland Int'l,

49 F.3d 807 (1st Cir. 1995) ....... ....... 6

Lucent Techs., Inc. v. Gateway, Inc.,

580 F.3d 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2009) ..................... ........ 17

MEMC Elec. Materials, Inc. v. Mitsubishi Materials Silicon,

420 F.3d 1369 (Fed. Cir. 2005) ....................... ........ 16

McKeon Prods., Inc. v. Flent Prods. Co.,

2002 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27123 (E.D. Mich. Nov. 19, 2002) ........ ........ 11

vi

Merch. & Evans, Inc. v. Roosevelt Bldg. Products Co., Inc.,

963 F.2d 628 (3d Cir. 1992) ...................... ....... 8

Mgmt. Sys. Assocs., Inc. v. McDonnell Douglas Corp.,

762 F.2d 1161 (4th Cir. 1985) .......................... 29

Miller v. Eagle Mfg. Co.,

151 U.S. 186 (1894) .............. ....... 7

Mirror Worlds, LLC v. Apple Inc.,

2011 WL 6939526 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 10, 2011) ...... ........ 17

Molski v. M.J. Cable, Inc.,

481 F.3d 724 (9th Cir. 2007) .................................... 1

Monolithic Power Sys., Inc. v. 02 Micro Int'l Ltd.,

476 F. Supp. 2d 1143 (N.D. Cal. 2007) ............... ..,..... 21

MyMail, Ltd. v. Am. Online, Inc.,

476 F.3d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2007) ...................., ........ 27

N Am. Philips Corp. v. Am. Vending Sales, Inc.,

35 F.3d 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1994) ....................... ........ 29

Nissan Motor Co. v. Nissan Comp. Corp.,

378 F.3d 1002 (9th Cir. 2004) ................. ......... 10, 11

OddzOn Prods., Inc. v. Just Toys, Inc.,

122 F.3d 1396 (Fed. Cir. 1997) ........ .......... 4

PHG Techs., LLC v. St. John Cos.,

469 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2006) ........... ....... 7

Pennwalt Corp. v. Durand-Wayland Inc.,

833 F.2d 931 (Fed. Cir. 1987) ........................... ........ 13

Princeton Biochemicals, Inc. v. Beckman Ins., Inc.,

180 F.R.D. 254 (D.N.J. 1997) ........................... 16

Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Elec., Inc.,

553 U.S. 617 (2008) .............,.............. ........ 29

Read Corp. v. Portec, Inc.,

970 F.2d 816 (Fed. Cir. 1992) ................. 5

ResQNet.com, Inc. v. Lansa, Inc.,

594 F.3d 860 (Fed. Cir. 2010) ..........

......19, 23,24

Richardson v. Stanley Works, Inc.,

597 F.3d 1288 (Fed. Cir. 2010) ............4

Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., Inc.,

56 F.3d 1538 (Fed. Cir. 1995) .................. 21

vii

Rotec Indus., Inc. v. Mitsubishi Corp.,

215 F.3d 1246 (Fed. Cir. 2000) ................... 16

SRI Int'l, Inc. v. Advanced Tech. Lab., Inc.,

127 F.3d 1462 (Fed. Cir. 1997) ............................. 24

Sea Hawk Seafoods, Inc. v. Alyeska Pipeline Serv. Co.,

206 F.3d 900 (9th Cir. 2000) .................................... 3

Seagate Tech., Inc. v. Hogan,

Case No. MS-93-0919 (Santa Cruz Mun. Ct. June 30, 1993) ................ 2

In re Seagate Techs., Inc. v. Gateway, Inc.,

497 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2007) ...................... 15

Sealant Sys. Int.‚ Inc. v. TEK Global,

2012 WL 13662 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 4, 2012) ................ 15

Sears v. Stiffel,

376 U.S. 225 (1964) .............. 8

Solannex, Inc. v. Miasole,

2011 WL 4021558 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2011) ................. 15

Spine Solutions, Inc. v. Medtronic Sofamor Danek USA, Inc.,

620 F.3d 1305 (Fed. Cir. 2010) .................. ........ 15

Sunbeam Prod., Inc. v. Wing Shing Prod (BVI) Ltd.,

311 B.R. 378 (S.D.N.Y. 2004) ............................. 21

Talking Rain Bev. Co., Inc. v. South Beach Bev. Co.,

349 F.3d 601 (9th C1r. 2003) ............................. 9

Tegal Corp. v. Tokyo Elec. Co.,

248 F.3d 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2001) ............... 17

Telcordia Techs., Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc.,

612 F.3d 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2010) ................... 17

Textron,

753 F.2d at 1025 .................... ........ 11

Tie Tech, Inc. v. Kinedyne Corp.,

296 F.3d 778 (9th Cir. 2002) .................. ....... 8

Titan Tire Corp. v. Case New Holland Inc.,

566 F.3d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2009) .......,....................... 7

TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc.,

532 U.S. 23 (2001) ......................... ...... 8, 9, 16

Transocean Offshore Deepwater Drilling, Inc. v. Maersk Contractors USA, Inc.,

617 F.3d 1296 (Fed. Cir. 2010) .................. 29

viii

U.S. v. 4.0 Acres of Land,

175 F.3d 1133 (9th C1r. 1999) ................................ 1

Uniloc USA, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp.,

632 F.3d 1292 (Fed. Cir. 2011), reh'g denied (Mar. 22, 2011) ......... 15

United States. v. Colombo,

869 F.2d 149 (2d Cir. 1989) ................. 2

United States v. Gonzalez,

214 F.3d 1109 (9th Cir. 2000) ................. 2

United States v. Perkins,

748 F.2d 1519 (11th Cir. 1984) ...................... 3

In re Velvin R. Hogan and Carol K. Hogan,

Case No. 93-58291-MM (Bankr.N.D. Cal. Dec. 27, 1993) ................. 2

Verizon Servs. Corp. v. Vonage Holdings Corp.,

503 F.3d 1295 (Fed. Cir. 2007) ............................ 19, 28

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc.,

529 U.S. 205 (2000) ....................................... 8

WhitServe, LLC v. Computer Pack., Inc.,

_ F.3d _, 2012 WL 3573845 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 7, 2012) ........... 23

Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co. v. Cadbury Adams USA LLC,

683 F.3d 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2012) .................... 16

Statutes

15 U.S.C. § 1111 ....................... 24, 26

15 U.S.C. § 1114 ............. 26

15 U.S.C. § 1117(a) ................ 27

15 U.S.C. § 1125(a) ................ 26

15 U.S.C. § 1125(c) ................... 1

15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(2)(B) .............. 11

35 U.S.C. § 1125(c) ................. 11

35 U.S.C. § 171 ................. 4

35 U.S.C. § 271 ................. 1

35 U.S.C. § 271(a) ............... 16

35 U.S.C. § 271(b) ......................... 17

ix

35 U.S.C. § 284 ..................27

35 U.S.C. § 287(a) ............... 24

35 U.S.C. § 289 ....... ......... 19, 21

Fed. R. Civ. P. 49 .............. 1, 14

Fed. R. Civ. P. 50(a) .............. 1

Fed. R. Civ. P. 50(b) ........................ 1

Fed. R. Civ. P. 59 ................... 1, 25, 31

Fed. R. Evid. 606(b)(1) ...................... 2

x

NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on December 6, 2012, at 1:30 p.m., before the Honorable

Lucy H. Koh, Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Samsung Electronics America, Inc., and Samsung

Telecommunications America, LLC (collectively "Samsung") shall and hereby do move the Court

for judgment as a matter of law pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 50(b), renewing Samsung's prior

request pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 50(a), and alternatively for a new trial or remittitur pursuant to

Fed. R. Civ. P. 59, as to each and every claim and issue on which Apple prevailed before the jury,

including both parties' claims for patent infringement pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 271, Apple's claims

for trade dress dilution pursuant to 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c), and Apple's claims for damages, as more

fully set forth below. Samsung additionally requests new trial or hearing pursuant to Fed. R. Civ.

P. 49. This motion is based on the memorandum of points and authorities below, the trial record,

the accompanying declarations of Susan Estrich, John Pierce, and Michael Wagner, all pleadings

and papers on file in this action, such matters as are subject to judicial notice, and all other matters

or arguments that may be presented in connection with this motion.

MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES

Judgment as a matter of law under Fed. R. Civ. P. 50(b) is required where a plaintiff fails

to present a legally sufficient basis for a reasonable jury to rule in its favor. Lakeside-Scott v.

Multnomah Cly., 556 F.3d 797, 802 (9th Cir. 2009). A new trial is appropriate under Fed. R. Civ.

P. 59 where "'the verdict is against the weight of the evidence, [] the damages are excessive, or []

for other reasons, the trial was not fair to the party moving.'" Molski v. MJ Cable, Inc., 481

F.3d 724, 729 (9th Cir. 2007); Rattray v. City of National City, 51 F.3d 793, 800 (9th Cir. 1994)

(same, prevent "miscarriage of justice"); Advanced Display Sys., Inc. v. Kent State Univ., 212 F.3d

1272, 1275 (Fed. Cir. 2000) (same, for "prejudicial legal error" in jury instructions). Remittitur

is appropriate under Rule 59 where the damages awarded by the jury are not supportable, and the

"proper amount of a remittitur is the maximum amount sustainable by the evidence." Jessen

Elec. & Serv. Co. v. Gen. Tel. Co., 106 F.3d 407 (9th Cir. 1997). Samsung is entitled to

judgment as a matter of law, new trial, or remittitur here for the reasons below.

1

[REDACTED]

2

[REDACTED]

3

II. SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW OR A NEW

TRIAL ON APPLE'S DESIGN PATENT INFRINGEMENT CLAIMS

A. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Infringement of Apple's Design Patents

The key to design patent infringement is whether a "hypothetical ordinary observer who is

conversant with the prior art" would in purchasing be deceived by similarities with an accused

product when focusing only on the ornamental features of the claimed designs. Egyptian

Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 678 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Design patent law protects only

designs that are new, original and ornamental, 35 U.S.C. § 171, not "general design concepts,"

OddzOn Prods., Inc. v. Just Toys, Inc., 122 F.3d 1396, 1405 (Fed. Cir. 1997), or a design's

"functional" and "structural" elements or "basic configuration," Lee v. Dayton-Hudson, 838 F.2d

1186, 1188 (Fed. Cir. 1988). Unprotected attributes must be "factored out" when analyzing

infringement, with only the remaining elements compared to the accused designs. Richardson v.

Stanley Works, Inc., 597 F.3d 1288, 1293 (Fed. Cir. 2010); OddzOn Prods, 122 F.3d at 1405.

Even differences between the patented and accused designs that are so minor that they "might not

be noticeable in the abstract can become significant" in light of prior art. Egyptian Goddess, 543

F.3d at 678.

1

The record fails to support the jury's finding of infringement of any of Apple's design

patents under these standards. Apple conceded that some attributes of its designs were functional

or otherwise unprotectable. E.g., RT 1197:13-17; 1199:25-1200:4 (Bressler admitting "a clear

cover over the display element" is "absolutely functional"); 1438213-19; 144027-12; 1474:5-76:7

(Kare admitting Apple's patents do not protect features like use of "the color green for go" on

icon, or images of clock, or square shapes with rounded comers, or "colorful matrix of icons"

arranged in grid). Apple conceded that it did not limit its infringement analysis to new and

ornamental designs. RT 1090:12-22 (Bressler did not factor out functional elements); 1470212-

4

16; 3475:1-24 (Kare did not consider functionality). And Apple failed to show that an ordinary

observer would be deceived by similarities, admitting that, "by the end of the smartphone

purchasing process, the ordinary consumer would have to know which phone they were buying."

RT 1103113-1104:18.2 Judgment as a matter of law for Samsung is therefore required. Read

Corp. v. Portec, Inc., 970 F.2d 816, 825 (Fed. Cir. 1992).

The D'677 and D'087 Patents. The jury should have factored out the non-ornamental

elements of these design patents in assessing infringement, especially since the record showed that

those designs are largely devoid of ornamentation (RT 1145319-23 (designs do not "have much

ornament"); RT 522:8-12 (Apple wanted iPhone to be "as simple as possible")). The record

showed that the non-ornamental elements included designs that are rectangular and have curved

corners; have flat, clear, large screens; are of a size that can be handheld; are black; and have

speakers near the top, opaque borders and a bezel. RT 675:5-12; 678:5-680:15 (larger screens

benefit users, black and opaque borders hide components, speaker near top is required for sound,

and round comers "help you move things in and out of your pocket"); RT 119918-1200:4

(transparent cover). Moreover, as Apple admitted, the prior art discloses numerous elements of

these designs, including at least a "rectangular" display screen that is "balanced vertically and

horizontally within the design," "rounded comers," "narrower lateral borders," "larger borders

above and below the screen," a bezel, and a "lozenge shaped" speaker placed in the top border.

RT 1110:23-1 12114, 117511-4 (referencing DX511, DX727, DX728 and JX1093).

Considering only the ornamental attributes of Apple's designs in light of the prior art, no

reasonable jury could find infringement of the D'677 and D'087 patents by any accused device.

Apple's expert Peter Bressler admitted that "details are important" and "contribute to how an

5

ordinary observer forms an overall impression" and pointed to the "very specific proportion[s]" of

Apple's phone designs and the "very specific impression" those dimensions create. RT 1016:11-20, 101925-8, 1133:9-ll, 115728-12. Apple distinguished its own designs from the prior art

based on "little differences" in details. RT 361326-11; 1154:3-15 (distinction in "lateral

borders"); 117626-21 (distinction that "lozenge shaped speaker opening" is "centered"); 1351217-1352:10, 3597:10-3598:1 (prior art is "not absolutely flat all the way across the front"); 1121:7-10

(absence of bezel in prior art). The types of differences that suffice to separate Apple's designs

from prior art also suffice to prevent a finding of infringement. Int'l Seaway Corp. v. Walgreens

Corp., 589 F.3d 1233, 1240 (Fed. Cir. 2009). Comparison of Samsung's products and Apple's

designs shows such differences and more exist here, as Apple's expert admits. RT 1176213-1178:25 (locations of speaker slots); 1126:10-1127:24, 113117-1132:1, 1138:5-114027 (absence of

bezel, differing shapes or forms of bezels); 1143:2-16 (shapes of corners); 1162:18-23 (additional

keys).

The D'305 Patent. Nor could any rational jury have found infringement of the D'305

when limited to its ornamental visual impression. Apple does not own the concept of colorful

icons arranged in a grid of square icons with rounded corners, nor can Apple claim protection over

the functional aspects of the D'305 design, including the use of pictures and images as "visual

shorthand" to communicate information (RT 1452:1-1455:25), the inclusion of sufficient space

between icons to allow for finger-operation (RT 1467:3-1468:22), and other elements discussed

above.

3 Apple's expert Susan Kare admitted that differences abound between the accused

Samsung products and Apple's designs, including the selection, location and shapes of, and

images on, the icons. RT 142612-1435:24; 144427-23. Apple only attempted to claim 2 of the

20 Samsung icons were substantially similar to Apple's icons. RT 142912-l430:25; 1433:9:-1435:24; 1444:7-23. Apple admitted that the home screen of the accused products "doesn't, in

6

fact, look like the patent" (RT 1397:1-4); the fact that users are required to pass through start-up

screens that say "Samsung" and the names of the products at issue (RT 1422114-142422) shows

there is no risk of deception. Contessa Food Prods., Inc. v. Conagra, Inc., 282 F.3d 1370, 1381

(Fed. Cir. 2002) (ordinary observer test considers "normal use of the product"). The Court

should enter judgment for Samsung of non-infringement on all three of Apple‚'s design patents, or

order a new trial.

B. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Apple's Design Patents Valid

The Court also should enter judgment on Apple's design patents because no rational jury

could find those patents valid. First, Apple's design patents are all invalid as functional in light

of the evidence discussed above. PHG Techs., LLC v. St. John Cos., 469 F.3d 1361, 1366 (Fed.

Cir. 2006) ("If the patented design is primarily functional rather than ornamental, the patent is

invalid.").4 Second, the D'677 and D'087 patents are invalid as obvious based upon the prior art

(including the JP'638, as well as the JP'383, KR'547, and LG Prada) that Apple admitted

displayed design characteristics of the asserted patents (RT 258139-2590:18; 2591:2593:20;

2595:7-22; DX511; DX727; DX728; JX1093). Titan Tire Corp. v. Case New Holland Inc., 566

F.3d 1372, 1380-81 (Fed. Cir. 2009). Third, the D'677 patent is invalid for double-patenting.

Miller v. Eagle Mfg. Co., 151 U.S. 186, 198 (1894) (second patent must be "substantially

different" from first). D'677 and embodiments of D'087 (particularly the sixth embodiment)

depict the same design; the only elements added by the D'677 are the color black and oblique

lines, features that do not make D'677 "a separate invention, distinctly different and independent,"

id at 198, and the D'087 subsumes the D'677 because Apple admits that "the flat front surface [of

D'087] could be any color. It could be transparent. It could be anything." RT 1019212-17.5

7

Fourth, the D'889 patent is also invalid as obvious in light of prior art including the TC1000 and

the 1994 Fidler tablet (JX1074; JX1078; DX 805; RT 2595:23-2601:17 (prior art shares "overall

rectangular shape with evenly rounded corners," "transparent, flat front cover," "very large

display," "flat front surface that goes across the whole front face up to a relatively thin rim,"

"relatively narrow profile," "almost identical to the proportions of the D'889," "flat back")), and

as functional given Apple's admissions that it does not own the "use of a rectangular shape with

rounded comers" or "the use of a large display screen for an electronic device." RT 3609:9-3611:10; DX 810. The Court should enter judgment of invalidity or order a new trial.

III. SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW OR A NEW

TRIAL ON APPLE'S TRADE DRESS CLAIMS

A. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Apple's Trade Dress Protectable

"The traditional interest in trademark protection is stretched very thin in dilution cases

where confusion is absent," as here, and unlike patent protection, which is time-limited, trade

dress law poses special dangers if used to give "permanent protection" to "the design of an article

of manufacture." I.P. Lund Trading ApS v. Kohler Co., 163 F.3d 27, 53 (lst Cir. 1998) (Boudin,

J., concurring).6 These concems have constitutional dimension.7

Accordingly, trade dress is not protected if doing so would impose "significant non-reputation-related disadvantages" on competitors. TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays,

Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 33-35 (2001); Au-Tomotive Gold Inc. v. Volkswagen of Am., Inc., 457 F.3d

1062, 1072 (9th Cir. 2006). Protection is limited to "identification of source," and does not

8

extend to "usefulness," id. at 1073, or "features which constitute the actual benefit that the

consumer wishes to purchase," Tie Tech, Inc. v. Kinedyne Corp., 296 F.3d 778, 785 (9th Cir.

2002).

8 No reasonable jury could fail to find Apple's claimed trade dress functional under

Inwood Labs, Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 US. 844 (1982), for Apple's own evidence confirmed

that its trade dress is "essential to the use or purpose of the article" and "affects [its] cost or

quality." Au-Tomotive Gold, 457 F.3d at 1072 (quoting Inwood).

9 For example, the claimed

trade dress had a clear face covering the front of the iPhone (RT 1199225-12O0:16 ("absolutely

functional")); rounded corners (RT 680:9-15 ("help you move things in and out of your pocket"));

a large display screen (RT 674120-675224 ("a benefit to users")); a black color (RT 679115-20

("hide internal wiring and components"); familiar icon images (RT 2533:25-2534:15); and a

useful size and shape (DX5622.001 ("size and shape/comfort benefits")).

Moreover, Apple's trade dress is unprotectable on account of its aesthetic functionality.

Apple argued that its trade dress was designed to be aesthetically appealing and that aesthetic

beauty is a primary motivator for consumer purchases. RT 484:1-11 (in designing iPhone, Apple

sought a "beautiful object"); 602:8-19 (iPhone is "beautiful and that that alone would be enough to

excite people and make people want to buy it"); 625:4-626:4 ("reasons for the iPhone success" are

"people find the iPhone designs beautiful" and "it's an incredibly easy-to-use device."); 635:23-636:5 ("attractive appearance and design" motivates purchases); 721:3-7 (customers "lust after

[iPhone] because it's so gorgeous"). Apple cannot use design patents to protect these same features and then obtain a perpetual monopoly in allegedly desirable designs under trade dress

9

law. E.g., Elmer V. ICC Fab., Inc., 67 F.3d 1571, 1580 (Fed. Cir. 1995) (trade dress functional

where it "was broadly defined to be essentially coextensive with, and in fact broader than, the

patent claim"); Duraco Prod., Inc. v. Joy Plastic Enter., Ltd., 40 F.3d 1431, 1453 (3d Cir. 1994).

Secondary meaning requirements likewise limit trade dress protectability to cases where

"the primary significance of a product feature or term is to identify the source of the product rather

than the product itself." Inwood, 456 US. at 851 n.11. No rational jury could find secondary

meaning on the record here, for the evidence failed to show that consumers believed the primary

significance of the asserted trade dress was to identify it with Apple. Apple's survey established

only that a majority of respondents shown blurred images of iPhones said they associate the

"overall appearance" of the phone with "Apple" or "iPhone" (RT 1583:10-1584:24), but that is

insufficient because a plaintiff "must show that the primary significance of the term in the minds

of the consuming public is not the product but the producer." Kellogg Co. v. Nat'l Biscuit Co.,

305 U.S. 111, 118-19 (1938). Apple's evidence that it advertised the iPhone as a whole (PX 11-14) is insufficient as well; the differences here between Apple's iPhone product (which includes

the Apple logo, trademark, and home button) and its generic claimed trade dress (which does not)

undermine the claim that advertising the product as a whole created secondary meaning. First

Brands Corp. v. Fred Meyer, Inc., 809 F.2d 1378, 1383 (9th Cir. 1987).

For these reasons, the Court should grant judgment as a matter of law that Apple's trade

dress is not protectable, or order a new trial.

B. No Reasonable Jury Could find Actionable and Willful Dilution

Nor did the evidence establish crucial elements of trade dress dilution and damages.

First, "to meet the 'famousness' element," "a mark [must] be truly prominent and renowned"

among the general public. Avery Dennison, 189 F.3d at 875 (quoting I.P. Lund, 163 F.3d at 46)).

This must have been so prior to the time of Samsung's sales of accused products. Nissan Motor

Co. v. Nissan Comp. Corp., 378 F.3d 1002, 1013 (9th Cir. 2004).10 The record contains no

10

evidence of such fame. Apple offered no survey restricted to the time before Samsung entered

the market, and its June 2011 survey shows recognition by less than 64% of likely cell phone

purchasers (not the general population). RT 1578224-1579:4; l584:17-l585:5; see Nissan, 378

F.3d at 1014 (65% awareness insufficient); Textron, 753 F.2d at 1025; 4 MCCARTHY ON

TRADEMARK at § 24:106, 24-310 (2008 ed.) ("75% of the general consuming public of the United

States" is required). Much of Apple's advertisement and press coverage evidence (PX 12-14)

was dated after Samsung's alleged first use, rendering it irrelevant; it focused on the product as a

whole and its appealing features, not the source-identifying features of the claimed trade dress;

and in any case, the consumer response to this advertising is already reflected in Apple's survey

results, which show insufficient fame.

Second, the record does not support a finding of likely dilution. Apple offered no

evidence that the accused Samsung phones "impair the distinctiveness" of Apple's trade dress. 15

U.S.C. § 1l25(c)(2)(B). See RT 1534214-21 ("no empirical evidence" and "no hard data to show

that Samsung's actions have diluted Apple's brand"). And proof of at least 25 third-party

smartphones bearing similar trade dress to that claimed by Apple (see Ex. 712 (third-party phones

with similar trade dress elements); RT 893216-25; 895:12-20 (market contains many smartphones

that look similar)) undermines any finding of likely dilution. McKeon Prods., Inc. v. Flent

Prods. Co., 2002 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 27123, at *34-35 (E.D. Mich. Nov. 19, 2002) (rejecting

dilution claim where "retailers typically have at least hundreds of products with blue and yellow

and white packaging" so that "[p]laintiff's colored packaging does not stand out in retail stores.").

Third, "willfulness" is a required element for any award of trade dress dilution damages.

35 U.S.C. § ll25(c) (damages available only when a party "willfully intended to trade on the

recognition of the famous mark"). Willfulness requires that a party "willfully calculate[s] to

exploit the advantage in an established mark," and mere copying does not suffice. Bandag, Inc.

v. Al Bolser's Tire Stores, Inc., 750 F.2d 903, 920-21 (Fed. Cir. 1984). Apple failed to introduce

any evidence, let alone clear and convincing proof, that Samsung intended to trade on the source-

11

identifying attributes of Apple's trade dress.11 Apple did not even contend it notified Samsung of

any asserted trade dress, much less establish Samsung knew its conduct was infringing. RT

1968:2-11 (no mention of trade dress in presentations to Samsung); PX 52; DX 800.

For these reasons, the Court should also grant judgment as a matter of law or a new trial on

trade dress dilution liability and damages.

IV. SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW OR A NEW

TRIAL ON APPLE'S UTILITY PATENT INFRINGEMENT CLAIMS

A. No Reasonable Jury Could find Apple's Utility Patents Valid

No reasonable jury, applying correct standards, could find Apple's utility patents valid.

Samsung's expert testified that Fractal Zoom and Nomura, which both scroll or zoom by

distinguishing between one or two or more input points, anticipate or render obvious every

limitation of claim 8 of the '915 patent. RT 2897:12-2902:5, 2908:1-7, 2903:15-2907:25 (Gray

invalidity testimony). The record contains no evidence to support any contrary finding. There

is also no dispute that Fractal Zoom and Nomura are l02(a) and (b) prior art to the '915 patent.

RT 228514-2290:20; 2275224-2290220, 2350:15-2357:l8, 236218-2366119; 290226-24; DX 550

(Bogue, Forlines and Gray testimony establishing prior art dates).

Samsung's expert also testified that TableCloth and LaunchTile, which both have the

claimed snap-back behavior, anticipate or render obvious every limitation of claim 19 of the '381

patent. RT 2854:18-2858:22; 2860:3-2864:11; 2864:24-2870:22; 2872:17-2873:9 (van Dam

invalidity testimony). The record contains no evidence to support any contrary finding, and it is

undisputed that TableCloth and LaunchTile are 102(a) and (b) prior art to the '381 patent. RT

2293:9-23; 2363:7-13; 2275:24-2282:4; 2290:21-2299:16; 2350:15-2351:8; 2357:19-2364:5;

2247:22-2248:13; 2229:14-2253:16 (Bogue, Forlines, Bederson and van Dam testimony

establishing prior art dates).

Samsung's expert testified that LaunchTile, Agnetta, and Robbins, which all exhibit the

12

claimed enlarging and centering behavior, anticipate or render obvious every limitation of claim

50 of the '163 patent. RT 2913:2-2917:2; 2917:3-2919:16; 2919:17-2922:6 (Gray invalidity

testimony). The record contains no evidence to support any contrary finding, and there is no

dispute that these references are 102(a) and (b) prior art. RT 2247:22-2248:13; 2229:14-2253:16; 2919:17-2920:14; JX 1081; 2917:3-22; DX 561; JX 1046 (Bederson and Gray testimony

establishing prior art dates). The Court should enter judgment of invalidity or order a new trial.12

B. No Reasonable Jury Could Find Infringement Of Apple's Utility Patents

The Court should also enter judgment of non-infringement as to each accused product.

To establish infringement, Apple must show the presence of every limitation in the accused

product. Pennwalt Corp. v. Durand-Wayland, Inc., 833 F.2d 931, 935 (Fed. Cir. 1987) (en

banc>), overruled in part on other grounds, Cardinal Chem. Co. v. Morton Int'1, 508 U.S. 83

(1993). When multiple products are accused, this showing must be made as to each product; a

patentee "cannot simply 'assume' that all of the [accused] products are like the one [patentee's

expert] tested and thereby shift to [the defendant] the burden to show that is not the case." L&W,

Inc. v. Shertech, Inc., 471 F.3d 1311, 1318 (Fed. Cir, 2006). For the '915 and '163 patents,

Apple's expert performed a limitation-by-limitation analysis of only one product, the Samsung

Galaxy S II (T-Mobile) (RT 1819:18-1831:7, 1833:21-1840:22), and then introduced videos of the

other 23 accused devices with no infringement analysis (RT 1829:12-1830:13; 1840:23-1842:6).

For the '381 patent, Apple's infringement analysis for the Gallery application was also limited to a

single product, the Samsung Galaxy S II (AT&T) (RT 1741:15-1747:23; 1751:19-1753:12); and

for the Contacts application the record contains no source code evidence or even demonstrative

videos for six accused products (the Continuum, Epic 4G, Galaxy S (i9000), Galaxy S II (i9l00),

Indulge, and Mesmerize) (RT 1753:13-1755:2l). This fails to meet Apple's burden of proof.

Separately, the record does not support any infringement of the '915 patent because the

event object does not cause a scroll or gesture operation as required by claim 8. Dkt. 1158 at 20;

13

RT 2910:18-22; 2911:6-2912:1. Apple identified the MotionEvent object in Samsung's devices

as the claimed event object (RT 1821:25-1822:17), but it is the WebView object, not the

MotionEvent object, that causes the scroll or gesture operation; the MotionEvent object causes

nothing. RT 2911:6-2912:1 (Gray non-infringement testimony). Apple admits that the "all-important test" for infringement of the '915 patent is found in the limitation "distinguishing

between a single input point...that is interpreted as the scroll operation and two or more input

points...that are interpreted as the gesture operation." RT 1826:12-15; 1857:2-24 (Singh

testimony). But that limitation is not satisfied: because a device that scrolls with two fingers

does not meet this test (RT 2896:5-12, 2912:2-19; 1860:15-1862:10), some Samsung products

allow for such scrolling (RT 1862:22-1865:9; 2912:2-19), and the record contains no evidence of

any that do not, the jury could not find infringement of the '915 patent.

A new trial is also necessary due to inconsistencies in the jury's verdict on the '915

patent. The jury found that the Ace, Intercept, and Replenish devices do not infringe the '915

patent but the remainder of the accused devices do. These verdicts are irreconcilably inconsistent,

for the Ace, Intercept and Replenish exhibit the same behavior as devices found to infringe,

including the Droid Charge, Indulge, Epic 4G, Infuse 4G, Transform and Prevail. The same

Android version found in the non-infringing Ace (Android 2.2.1) and the Intercept and Replenish

(Android 2.22) are found in these other devices which the jury found to be infringing. A new

trial is therefore warranted under Fed. R. Civ. P. 49. Los Angeles Nut House v. Holiday

Hardware Corp., 825 F.2d 1351, 1356 (9th Cir. 1987).

No reasonable jury could have found infringement of the '381 patent either. The Court

previously found the claims of this patent to require the electronic document to always snap back.

Dkt. 452 at 58-60. Samsung's products do not do so, using instead a "hold still" feature which

Apple's expert admitted does not infringe. RT 1792:16-1793:7; 1796:22-1797:7 (Balakrishnan

non-infringement testimony). This feature does not translate the electronic document into a

second direction, as required by the last limitation of Claim 19. RT 1791:14-1799:4.

Samsung's products also exhibit a "hard stop" behavior, wherein they do not display an area

beyond the edge of the electronic document at all. Apple admits this "hard stop" behavior does

14

not infringe the '381 patent. RT 1785:19-1787:3 (Balakrishnan non-infringement

testimony). Accordingly, judgment of non-infringement should enter.

V. THE RECORD LACKS CLEAR AND CONVINCING EVIDENCE OF WILLFUL

INFRINGEMENT

Willfulness requires clear and convincing proof (1) to the jury that Samsung subjectively

knew or recklessly disregarded that particular patents were valid and infringed, and (2) to the

Court of an objectively high likelihood of such infringement. Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc. v.

Gore & Assoc. Inc., 682 F.3d 1003, 1007 (Fed. Cir. 2012); In re Seagate Techs., Inc. v. Gateway,

Inc., 497 F.3d 1360, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (en banc). Willfulness is assessed "on a claim by

claim basis." Highmark, Inc. v. Allcare Health Mgmnt. Sys., Inc., 687 F.3d 1300, 1311 (Fed. Cir.

2012). Knowledge of the asserted patents is mandatory but insufficient. i4i Ltd. P'ship v.

Microsoft Corp., 598 F.3d 831, 860 (Fed. Cir. 2010).13 In "ordinary circumstances" the inquiry

focuses on the defendant's pre-suit knowledge because patentees "should not be allowed to accrue

enhanced damages based solely on the infringer's post-filing conduct"; the usual remedy for

alleged post-filing willful infringement is a preliminary injunction. Seagate, 497 F.3d at 1374.14

Here, proof of willfulness, objective as well as subjective, is deficient. The record

contains no evidence that Samsung knew of any Apple patent in issue other than the '381 patent;

the '915 and '163 patents, in particular, did not issue until November 30, 2010 and January 4,

2011, mere months before this litigation commenced. JX 1044, 1046. As to the '381, the record

shows only that it was listed amidst 75 other patents in Apple's 23-page August 2010 presentation,

without proof that it was ever discussed, belying any inference that Samsung was on notice of

those particular claims. PX 52 at 12-16; see RT 1958:17-1959:13 (Teksler unable to testify to

discussions). Even if Samsung's defenses as to validity and infringement do not prevail, they are

at least reasonable, which also forecloses a finding of willfulness. See Spine Solutions, Inc. v.

15

Medtronic Sofamor Danek USA, Inc., 620 F.3d 1305, 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2010); Uniloc USA, Inc. v.

Microsoft Corp, 632 F.3d 1292, 1310 (Fed. Cir. 2011), reh'g denied (Mar. 22, 2011); Black &

Decker, Inc. v. Robert Bosch Tool Corp., 260 F. App'x 284, 291 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

Nor is Apple's evidence of alleged "copying" sufficient, as -- far from showing willful

infringement -- copying is "of no import on the question of whether the claims of an issued patent

are infringed." DePuy Spine. Inc. v. Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Inc., 567 F.3d 1314, 1336 (Fed.

Cir. 2009); Goodyear Tire v. Hercules Tire, 162 F.3d 1113, 1121 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (no

infringement despite intent "to appropriate the general appearance of the Goodyear tire"),

abrogated on other grounds by Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 678; Hupp v. Siroflex of Am., 122

F.3d 1456, 1464-65 (Fed. Cir. 1997). Copying publicly-known information not protected by a

valid patent is fair competition, see TrafFix, 532 U.S. at 29; Bonito Boats, 489 U.S. at 159-60, and

it "is erroneous" to suppose "that copying is synonymous with willful infringement." Princeton

Biochemicals, Inc. v. Beckman Ins., Inc., 180 F.R.D. 254, 258 n.3 (D.N.J. 1997). Moreover, with

few exceptions these documents did not even address the patents or rights at issue here. There

can be no equation between copying and willful infringement of established patent rights. Wm.

Wrigley Jr. Co. v. Cadbury Adams USA LLC, 683 F.3d 1356, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

Accordingly, the Court should grant judgment to Samsung on willfulness, or a new trial.

VI. THE RECORD LACKS SUFFICIENT EVIDENCE OF DIRECT INFRINGEMENT

OR ACTIVELY INDUCED INFRINGEMENT BY SEC

Patent infringement "cannot be predicated on acts wholly done in a foreign country."

Rotec Indus., Inc. v. Mitsubishi Corp., 215 F.3d 1246, 1251 (Fed. Cir. 2000); see MEMC Elec.

Materials, Inc. v. Mitsubishi Materials Silicon, 420 F.3d 1369, 1375, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2005)

("Mere knowledge that a product sold overseas will ultimately be imported into the United States

is insufficient to establish liability under section 271(a)."). The record lacks sufficient evidence

that SEC engaged in any negotiations, signed any contracts, or offered for sale or sold any

products in the U.S.. The record also lacks sufficient evidence that SEC actively induced any

direct infringement in the U.S. under 35 U.S.C. § 27l(b). "To establish liability under section 271(b), a patent holder must prove that once the defendant knew of the patent, they actively and

16

knowingly aided and abetted another's direct infringement." DSU Med. Corp. v. JMS Co., 471

F.3d 1293, 1305 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (en banc). "[M]ere knowledge of possible infringement by

others does not amount to inducement; specific intent and action to induce infringement must be

proven." DSU, 471 F.3d at 1305; Tegal Corp. v. Tokyo Elec. Co., 248 F.3d 1376, 1379 (Fed. Cir.

2001) ("a failure to stop infringement" is insufficient).15 Apple offered no evidence of

inducement; the evidence establishes the opposite. RT 948:11-13; 900:12-24 (STA, SBA and

SEC have distinct management and employees; STA makes its own business decisions). The

Court should grant judgment of non-infringement by SEC, or order a new trial. In any event, a

new trial on damages is necessary because, as Apple's expert admits, the vast majority of Apple's

claimed damages are based on profits made by SEC. RT 2071:1-2072:1; 2072:2l -24; DX180.

VII. SAMSUNG IS ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT, NEW TRIAL AND/OR REMITTITUR

ON DAMAGES

Over Samsung's objection (RT 3853:5-3856:10), the Coun used a verdict form providing

for a single damages amount for each product without specifying the amounts attributable to

particular patents or trade dress or whether the award was derived from Samsung's profits,

Apple's lost profits, and/or a reasonable royalty. Dkt. 1931, at 15-16.16 Where, as here, the

basis for the jury's award is unclear, the Court may "work[] the math backwards" to determine the

basis for the award. Lucent Techs., Inc. v, Gateway, Inc., 580 F.3d 1301, 1336-37 (Fed. Cir.

2009); Telcordia Techs., Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 612 F.3d 1365, 1378 (Fed. Cir. 2010); In re First

Alliance Mortg. Co., 471 F.3d 977, 1002-03 (9th Cir. 2006). Comparison of the verdicts with the

amounts presented by Apple's expert Terry Musika in PX25A1 reveals the following:

- For each of the 11 Samsung phones (Captivate, Continuum, Droid Charge, Epic

4G, Galaxy S II 2 (AT&T), Galaxy S II (T-Mobile), Galaxy S II (Epic 4G Touch), Galaxy S II

(Skyrocket), Gem, Indulge, and Infuse 4G) for which the jury found infringement of one or more

17

design patents but no trade dress dilution, the jury awarded exactly 40% of Apple's claimed figure

for Sarnsung's profits. Wagner Decl. at ¶12.

- For each of the five Samsung phones (Fascinate, Galaxy S 4G, Galaxy S Showcase

(i500), Mesmerize, and Vibrant) for which the jury found infringement of one or more design

patents and trade dress dilution, the jury awarded exactly the amount of lost profits claimed by

Apple plus 40% of Apple's claimed figure for Samsung's profits. Id. at ¶ 13.

- For five of the seven Samsung products that were found to infringe only utility

patents (Exhibit 4G, Galaxy Tab, Nexus S 4G ('381 & '9l5), Replenish ('162 and '38l), and

Transform ('915)), the jury awarded exactly half of Apple's claimed royalties figure. Id. at ¶ l4.

- For the remaining two Samsung products found to infringe only utility patents, the

jury awarded exactly 40% of what Apple claimed as Samsung's profits on the Galaxy Prevail, and

$833,076 for the Galaxy Tab 10.1 (WiFi). Id. at ¶¶ 15-16.

- Accordingly, $948,278,061 of the verdict represents Samsung's profits:

($599,859,395 for 11 phones the jury found infringed design patents, $290,551,383 for five

phones the jury found infringed design patents and diluted trade dress, and the remaining

$57,867,383 for one phone found to infringe only utility patents); $91,132,279 of the verdict

represents Apple's lost profits for five Samsung phones found to infringe design patents and dilute

trade dress; $9,180,124 of the verdict represents Apple's royalties for five Samsung devices found

to infringe only utility patents; and $833,076 of the verdict represents an amount awarded for one

device found to infringe utility patents. Id. at ¶¶ 17-20.

A. The Record Lacks Sufficient Evidence To Support The Damages Verdict

1. The Award Of $948,278,061 For Samsung's Profits

Design Patent Infringement. Apple did not limit its calculations of Samsung's profits to

those attributable to use of the patented designs. While 35 U.S.C. § 289 allows an award for

patent infringement of an "article of manufacture" up "to the extent of [the infringer's] total

profit," it does not eliminate the requirement inherent in all patent infringement litigation that

causation must be shown. Carbice Corp. of Am. v. Am. Patents Dev. Corp, 283 U.S. 27, 33 (1931) (patent infringement is "essentially a tort"); see ResQNet.com, Inc. v. Lansa, Inc., 594 F.3d

18

860, 869 (Fed. Cir. 2010) ("At all times, the damages inquiry must concentrate on compensation

for the economic harm caused by infringement of the claimed invention."). Unless limited to the

portion of profits attributable to infringement of the patented design rather than other,

noninfringing features of accused devices, infringer's profits violate the causation requirement and

impose excessive damages far beyond any compensation or deterrence rationale. Cf

Laserdynamics v. Quanta Computer, Inc., _ F.3d. _, 2012 WL 3758093, at *l2 (Fed. Cir. Aug.

30, 2012) (limiting damages "in any case involving multi-component products" to "the smallest

salable patent-practicing unit" unless "demand for the entire product is attributable to the patented

features"); Junker v. HDC Corp., 2008 WL 3385819, at *5 (N.D. Cal. July 28, 2008) (applying

same rule to infringer's profits under section 289); Bush & Lane Piano Co. v. Becker Bros., 222 F.

902, 905 (2d Cir. 1915) and Bush & Lane Piano Co. v. Becker Bros., 234 F. 79, 81-82 (2d Cir.

1916) (applying same rule to predecessor statute to §289 and limiting infringer's profits to those

attributable to design of piano case rather than whole piano); see also Cornell Univ. v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 609 F. Supp. 2d 279, 286-87 (N.D.N.Y. 2009) (Rader, J.).

The record contains no evidence that the entire sales value of Samsung's products was

attributable to their outer casings or GUI, as opposed to the numerous noninfringing technological

components that enable the devices to function and drive consumer choice. Apple's own study

showed that only 1% of iPhone users said that design and color is the reason they chose a phone

(DX592.023), and just 5% of respondents to a J.D. Power study identified visual appeal as why

they purchased a phone. PX69.43 (all aspects of physical design comprised only up to 23% of

the reasons for consumer selections, and visual appeal amounted to only 22% of that 23%, or just

5% of the total). There was thus no evidence that infringement of the design of the outer casings

or GUI caused Samsung to receive $600 million in profits.

Trade Dress Dilution. "Trademark remedies are guided by tort law principles," and a

plaintiff may recover "profits only on sales that are attributable to the infringing conduct." Lindy

Pen Co. v. Bic Pen Corp., 982 F.2d 1400, 1407-08 (9th Cir. 1993). The record contains no

evidence that Samsung profited in an amount over $290 million on sales of five phones from

lessening the capacity of Apple's trade dress to identify and distinguish its goods or services. To

19

the contrary, Apple's expert, Professor Winer, admitted he had no empirical evidence to show

Samsung's actions have diluted Apple's brand, and he never quantified the amount of any alleged

harm from dilution or loss of any kind to Apple as a result of Samsung's actions. RT 1534:14-17; 1534:22-1535:11. Nor did Apple's damages expert Mr. Musika. In addition, as explained

above, supra, the evidence showed that design of a smartphone accounts for at most between 1%

and 5% of the reason consumers purchase a particular phone. See DX592.023; PX69.43.

Failure To Deduct Samsung's Operating Expenses. Mr. Musika calculated Samsung's

profits as gross revenue minus cost of goods sold. RT 2054:11-2055:2; PX34B.17-18. He did

not deduct any of Samsung's other operating expenses, even though he admitted Samsung

incurred those expenses. RT 2061:1-11. Using his method, "the overall gross profit percentage

on just the accused products was approximately 35.5 percent." RT 2060219-21. By contrast,

Samsung's expert Mr. Wagner testified to the operating expenses that Samsung incurred in

making the accused sales, which resulted in an average profit margin of 12%. RT 3022:7-3025:8, 3028:7-303l:23, 3074:23-3075:5. He also noted that the audited figures for Samsung's

Telecommunications segment showed its profit margin to be 15%, and the entire company's

profitability to be 10%. RT 3073:5-3074:22. There was no basis for Mr. Musika's failure to

deduct Samsung's operating expenses in arriving at his figures for Samsung's profits. See

Sunbeam Prod, Inc. v. Wing Shing Prod. (BVI) Ltd., 311 BR. 378, 401 (S.D.N.Y. 2004)

(appropriate to deduct fixed costs in determining infringer's profits under Section 289); adidas

Am., Inc. v. Payless Shoesource, Inc., 2008 WL 4279812, at *13 (D. Or. Sept. 12, 2008) (same for

operating costs in trademark case).

2. The Award of $91,132,279 For Apple's Lost Profits

A plaintiff in a patent infringement action must establish both but-for and proximate

causation between infringement and lost profits, Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., 56 F.3d 1538,

1545-46 (Fed. Cir. 1995), showing "likely outcomes with infringement factored out of the

economic picture." Crystal Semiconductor Corp. v. Tritech Microelecs. Int'l, Inc., 246 F.3d

1336, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (citation omitted). The record fails to support the award of $91 million in lost profits for five phones for several independent reasons.

20

First, Apple's damages expert failed to take price elasticity of demand into consideration,

even though it was undisputed that consumers would have had to pay $67 more for an iPhone than

a Samsung smartphone, and $240 more for an iPad than a Galaxy Tab." See id. at 1355-56

(requiring consideration of consumer reaction to products' "different prices"); Monolithic Power

Sys., Inc. v. 02 Micro Int'l Ltd., 476 F.Supp. 2d 1143, 1155-56 (N.D. Cal. 2007); cf. BIC Leisure

Prods., Inc. v. Windsurfing Int'l, Inc., 1 F.3d 1214, 1218-19 (Fed. Cir. 1993).

Second, Apple failed to show that consumer purchases were driven by the desire for

Apple's designs and inventions, as opposed to the functionality of Samsung's phones. Mr.

Musika referred to two Samsung documents, PX34 and PX194 (RT 2078:4-2083:3), but neither

discusses any of the Apple patented features or trade dress. With respect to utility patents, Mr.

Musika testified that he relied on Dr. Hauser's survey. RT 2077:1-8. But Dr. Hauser testified

for less than two minutes on direct (RT 1913:23 (Time: 3:28) to RT l9l6:16-17 (Time: 3:30)),

failed to offer any meaningful explanation, and admitted that his survey bears no relationship to

the real world. See RT 1935:16-1936:9.

Third, the evidence failed to show that, absent Samsung's infringement, Samsung

customers would have bought iPhones rather than a non-accused Android device from Samsung or

another manufacturer. As Apple's own research showed, just 25% of Android purchasers even

considered an iPhone. PX572.82; RT 2129:4-2132:6.

Fourth, neither Mr. Musika nor any other Apple witness offered any basis to conclude

Apple had "either or both" the "manufacturing and marketing capacity" to sell the "2 million

incremental units over the two year time period" on which he based his lost profits figures. RT

21

2085:10-20862:3.18 He also admitted that Apple had no capacity to manufacture additional

iPhone 4s for five months during the damages period. RT 2141:13-2142:13.

Fifth, Mr. Musika presented the jury with only one lost profits number per accused product

(PX25A1.4), assuming that each and every Samsung product infringed all of Apple's patents and

diluted all its trade dresses. RT 2114:15-2118:24; 2122:3-2123:6. Because the jury failed to

find infringement and dilution for all Apple's asserted rights, and lacked any basis in evidence to

adjust Mr. Musika's number on a per-product basis, the record fails to support any causation

between the liability findings and lost profits.19 Moreover, Mr. Musika's lost profits calculations

were based on the length of the design around periods for the intellectual property found to be

infringed. RT 20841:2-19. Yet, with the exception of a one-month design around period for the

'38l patent (RT 2123:12-24), Mr. Musika provided the jury with no basis to determine the length

of the design around period for any particular item of intellectual property (let alone the

reasonableness of that period), when the periods started or ended, or how changes in his notice

date assumptions impacted these variables, including whether the design around period had

already ended before the notice period even began. Wechsler v. Macke Int'l Trade, Inc., 486

F.3d 1286, 1294 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

3. The Award 0f $9,180,124 In Royalties

There was no evidence to support Mr. Musika's "ultimate conclusion" that a reasonable

per-unit royalty for each of the utility patents would be $3.10, $2.02, $2.02 (RT 2090:20-2091:2),

or that the combined royalty for all design patents and trade dress would be $24 per unit

(PX25A1.16; RT 2l64:23-25). Although Mr. Musika stated that he performed a Georgia-Pacific

analysis and used three valuation methods (RT 2088:20-21, 208922-17), he identified no specific evidence supporting his royalty rates. Such unsupported testimony is insufficient to support a

22

reasonable royalty award. WhitServe, LLC v. Computer Pack., Inc., _ F.3d _, 2012 WL

3573845, at *15 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 7, 2012) (reasonable royalty award unsupported by expert

testimony that was "conclusory, speculative and, frankly, out of line with economic reality"); see

also ResQNet.com, 594 F.3d at 869-872 (similar); Go Med. Indus., Ltd. v. Inmed Corp., 471 F.3d

1264, 1274 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (affirming JMOL rejecting unsupported trademark royalty).

Moreover, while Mr. Musika's royalty analysis assumes each Samsung product infringes

all Apple's claimed utility patents (RT 21141:15-2118:24; 2l22:16-2l23:6), the Nexus S 4G was

held not to infringe the '163 patent; the Replenish not to infringe the '915 patent; and the

Transform not to infringe the '38I or the '163 patent. Dkt. 1931. By using one-half of Mr.

Musika's calculated royalty, the jury improperly applied the same royalty rate to all five products,

despite the fact that the jury reached different conclusions about infringement.

B. The Damages Rest Upon An Incorrect Notice Date

Apple's patent infringement damages are limited to the time period after it gave Samsung

actual written notice of the allegedly infringed patents and the specifically accused products. See

35 U.S.C. § 287(a); Funai Elec. Co., Ltd. v. Daewoo Elecs. Corp., 616 F.3d 1357, 1373 (Fed. Cir.

2010); SRI Int'l, Inc. v. Advanced Tech. Lab., Inc., 127 F.3d 1462, 1470 (Fed. Cir. 1997); Amsted

Indus. Inc. v. Buckeye Steel Castings Co., 24 F.3d 178, 187 (Fed. Cir. 1994). Actual notice is

similarly a prerequisite for recovery of damages or profits for registered trade dress infringement

because Apple does not display the trade dress with the required statutory language identifying its

registration. See 15 U.S.C. § 1111; RT 2007:21-2008:l.

Mr. Musika based all of his damage estimates for patent infringement and registered trade

dress dilution on a notice date of August 4, 2010, the date of a meeting between SEC and Apple

representatives. PX25Al.2; RT 2095:6-21; 2l68:l8-2169:l0. But only the '38l patent was

mentioned in the associated presentation. PX52.l2-16; RT l965:22-1968:11. The earliest

notice Samsung received of the '915 and D'677 patents and App1e's registered trade dress was

Apple's filing of the April 15, 2011 complaint. RT 1968:20-1970:2. The earliest notice

Samsung received of the '163, D'305, D'889, and D'087 patents was Apple's filing of the June

16, 2011 amended complaint. Dkt. 1903 (final Instruction Nos. 42 & 57). Mr. Musika's

23

reliance on an erroneous notice date inflated the revenue he used to calculate Samsung's profits

and Apple's damages by more than $3.3 billion. See JX15OO; Wagner Decl. at 25, Because the

jury calculated Samsung's profits and Apple's damages based on Mr. Musika's use of an incorrect

notice date, the Court should vacate the award and grant a new trial on damages. See Litton Sys.,

Inc. v. Honeywell, Inc., 140 F.3d 1449, 1465 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (new trial required "if a jury may

have relied on an impermissible basis in reaching its verdict"); see also In re first Alliance, 471

F.3d 977, 1001-03 (9th Cir. 2006) (remanding for new trial and consideration of remittitur where

"one of the figures used" by jury to determine damages award was improper); Brocklesby v.

United States, 767 F.2d 1288, 1294 (9th Cir. 1985) (holding that "judgment must be reversed if

any of the three theories [underlying it] is legally defective").20

C. At A Minimum, The Jury's Damages Award Should Be Remitted

"[T]he proper amount of a remittitur is the maximum amount sustainable by the evidence."

Informatica Corp. v. Business Objects Data Integration, Inc., 2007 WL 2344962, at *4 (N .D. Cal.

Aug. 16, 2007). Remittitur is appropriate under Rule 59 "(l) where the court can identify an

error that caused the jury to include in the verdict a quantifiable amount that should be stricken . . .

and (2) more generally, where the award is 'intrinsically excessive' in the sense of being greater

than the amount a reasonable jury could have awarded, although the surplus cannot be ascribed to

a particular, quantifiable error." Cornell Univ., 609 F. Supp. 2d at 292 (citations omitted). Here

the Court has available numerous easily quantifiable bases to reduce the award:

1. Reduction Of $ 0,034,295 In Lost Profits

Because the lost profits portion of the jury's award on five phones (Fascinate, Galaxy S

4G, Galaxy S Showcase, Mesmerize and Vibrant) found to infringe design patents and dilute trade

dress rested on insufficient evidence, see supra, the Court should reduce the award on these phones by the amount of $70,034,295, leaving the amount awarded on those phones at most at

24

$311,649,267, which represents 40% of Mr. Musika's number for Samsung's profits on those

phones (PX25A1.5). Wagner Decl., ¶ 26.

2. Reductions of $253,328,000 And $220,952,000 To Reflect Correct Notice

Dates

Because Mr. Musika's profit calculations incorrectly assume an August 4, 2010 notice date

for each design patent at issue, see supra, the Court should reduce the jury's award of

$599,859,395 in Samsung's profits on the 11 phones found to infringe one or more design patents

but not to dilute trade dress by $253,328,000 to $346,531,495, which represents 40% of Mr.

Musika's calculation of Samsung's profits on these phones after adjustment for the correct notice

dates based on the filing of the complaint (for D '677) and the amended complaint (for D'087 and

D'305). Wagner Decl., ¶ 27. For the same reason, the Court should reduce the jury's award on

the five phones found to infringe design patents and dilute registered trade dress to correct for the

wrong August 4, 2010 notice date. Assuming the jury's lost profit award is already eliminated,

see supra, this adjustment yields an additional reduction in the amount of $220,952,000 to

$90,697,267 or 40% of Mr. Musika's calculation of Samsung's profits on these phones adjusted