| Trying Out Google's New Patent Search Tool: The Prior Art Finder ~pj Updated |

|

|

Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 09:01 AM EDT

|

Let's try out the new Google Patent Prior Art Finder that was just announced.

I suggest that we try the new tool out looking for prior art on the four Lodsys patents they are terrorizing the world with. Are you with me?

The four Lodsys patents are 5,999,908, 7,133,834, 7,222,078, and 7,620,565. Oracle already found a

lot of prior art, and it filed the long list with the court. But let's see if they missed anything that the new Google Prior Art Finder can locate. That would make it very useful indeed.

In order to help out, we need to try to grasp some relevant details about how patent law works. Obviously, if your work requires you to avoid patents, don't read the rest of this article.

Jump To Comments

We've done a lot of prior art searching on Groklaw, and you have proven effective time and time again, because you understand the technology. You know what the USPTO does not -- where to find prior art that isn't in the USPTO's database of patents that issued, particularly Free and Open Source prior art, because you've lived and worked in the field.

But the more you know about the law too, the more effective you will be. And finding prior art isn't the only way to knock a patent out. Let's look at all the ways, and then after that we'll try out the new prior art tool.

Here are the five requirements for patentability, from Cornell University Law School Legal Information Institute:

Requirements for Patentability

The five primary requirements for patentability are: (1) patentable subject matter, (2) utility, (3) novelty, (4) nonobviousness, and (5) enablement.

Patentable Subject Matter

The patentable subject matter requirement addresses the issue of which types of inventions will be considered for patent protection. Under 35 U.S.C. § 101, the categories for patentable subject matter are broadly defined as any process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or improvement thereof. In Diamond v. Chakrabarty, the Supreme Court found that Congress intended patentable subject matter to "include anything under the sun that is made by man." See Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980). However, the Court also stated that this broad definition has limits and does not embrace every discovery. According to the Court, the laws of nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable. The relevant distinction between patentable and unpatentable subject matter is between products of nature, living or not, and human-made inventions....

Utility

The second requirement for patentability is that the invention be useful. See 35 U.S.C. § 101. The PTO has developed guidelines for determining compliance with the utility requirement. The guidelines require that the utility asserted in the application be credible, specific, and substantial. These terms are defined in the Utility Guidelines Training Materials. Credible utility requires that logic and facts support the assertion of utility, or that a person of ordinary skill in the art would accept that the disclosed invention is currently capable of the claimed use. The utility must be specific to the subject matter claimed; not a general utility that could apply to a broad class of inventions. Substantial utility requires that the invention have a defined real world use; a claimed utility that requires or constitutes carrying out further research to identify or confirm a use in the context of the real world is not sufficient.

Novelty

The novelty requirement described under 35 U.S.C. § 102 consists of of two disctinct requirements; novelty and statutory bars to patentability. Novelty requires that the invention was not known or used by others in this country, or patented or described in a printed publication in this or another country, prior to invention by the patent applicant. See 35 U.S.C. § 102(a). To meet the novelty requirement, the invention must be new compared to the prior art. The statutory bar applies where the invention was in public use or on sale in this country, or patented or described in a printed publication in this or another country more than one year prior to the date of the application for a U.S. patent. See 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). In other words, the right to patent is lost if the inventor delays too long before seeking patent protection. An essential difference between the novelty requirement and statutory bars is that an inventor's own actions cannot destroy the novelty of his or her own invention, but can create a stutory bar to patentability.

Nonobviousness

Congress added the nonobviousness requirement to the test for patentability with the enactment of the Patent Act of 1952. The test for nonobviousness is whether the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the art at the time the invention was made. See 35 U.S.C. § 103.

The Supreme Court first applied the nonobviousness requirement in Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1 (1966). The Court held that nonobviousness could be determined through basic factual inquiries into the scope and content of the prior art, the differences between the prior art and the claims at issue, and the level of skill possessed by a practioner of the relevant art.

In 2007, the Supreme Court again addressed the test for nonobviousness. See KSR International Co. v. Teleflex, Inc. (04-1350). In KSR, the Court rejected the test for nonobviousness employed by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit as being too rigid. Under the "teaching, suggestion, or motivation test" applied by the Federal Circuit, a patent claim was only deemed obvious if "some motivation or suggestion to combine the prior art teachings can be found in the prior art, the nature of the problem, or the knowledge of person having ordinary skill in the art." The Court endorsed a more expansive and flexible approach under which "a court must ask whether the improvement is more than the predictable use of prior art elements according to their established functions."

Enablement

The enablement requirement is directly related to the specification, or disclosure, which must be included as part of every patent application. "The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains...to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor of carrying out his invention." See 35 U.S.C. § 112. At the end of the specification, the applicant lists "one or more claims particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter which the applicant regards as his invention." See 35 U.S.C. § 112. Enablement is understood as encompassing three distinct requirements: the enablement requirement, the written description requirement, and the best mode requirement.

Every patent application must include a specification describing the workings of the invention, and one or more claims at the end of the specification stating the precise legal definition of the invention. To satisfy the enablement requirement, the specification must describe the invention with sufficient particularity that a person having ordinary skill in the art would be able to make and use the claimed invention without "undue experimentation." See In re Wands, 858 F.2d 731 (Fed Cir. 1988). In In re Wands, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals listed eight factors to be considered in determining whether a disclosure would require undue experimentation. The Patent and Trademark Office has incorporated these factors in the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure. See MPEP 2164.01(a).

The written description requirement compares the description of the invention set out in the specification with the particular attributes of the invention identified for protection in the claims. It is possible for a specification to meet the test for enablement, but fail the written description test. The basic standard for the written description test is that the applicant must show he or she was "in possession" of the invention as later claimed at the time the application was filed. Any claim asserted by the inventor must be supported by the written description contained in the specification. The goal when drafting patent claims is to make them as broad as the PTO will allow. THe writing requirement imposes two important limitations: the applicant may not seek protection for a claim that is broader than the supporting specification; and, if the applicant intends to focus on a particular attribute of the invention in the claims, that attribute must be clearly indicated in the specification.

In addition to disclosing sufficient information to enable others to practice the claimed invention, the patent applicant is required to disclose the best mode of practicing the invention. See 35 U.S.C. § 112. The best mode requirement is violated where the inventor fails to disclose a preferred embodiment, or fails to disclose a preference that materially affects making or using the invention. See Bayer AG v. Schein Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 301 F.3d 1306 (Fed. Cir. 2002). A violation of the best mode requirement involves two essential elements: first, it must be determined whether the inventor actually had a preferred mode of practicing the invention at the time the application was filed; if it is established that the inventor did contemplate a best mode for practicing the invention, the question becomes whether sufficient information was disclosed to enable a person of ordinary skill in the art to practice the best mode of the invention.

Notice that three of the elements mention a person of ordinary skill in the art, or PHOSITA? That could be many of you, depending on the specific patent. The three are nonobviousness, utililty and enablement.

What Qualifies You As a PHOSITA?

Let's focus first on nonobviousness. After that I want to say a brief word about enablement and utility. Then we'll start to try out the prior art tool.

Obviousness is measured in patent law according to what an ordinary person skilled in the art would have known *at the time* the patent is being considered. Lots of things are obvious after the fact, but that doesn't count. There are some fine points, as you can see by this collection of what courts have said about this, found on the USPTO web site:

2141.03 Level of Ordinary Skill in the Art [R-6]

I.

The person of ordinary skill in the art is a hypothetical person who is presumed to have known the relevant art at the time of the invention. Factors that may be considered in determining the level of ordinary skill in the art may include: (A) "type of problems encountered in the art;" (B) "prior art solutions to those problems;" (C) "rapidity with which innovations are made;" (D) "sophistication of the technology; and" (E) "educational level of active workers in the field. In a given case, every factor may not be present, and one or more factors may predominate." In re GPAC, 57 F.3d 1573, 1579, 35 USPQ2d 1116, 1121 (Fed. Cir. 1995); Custom Accessories, Inc. v. Jeffrey-Allan Industries, Inc., 807 F.2d 955, 962, 1 USPQ2d 1196, 1201 (Fed. Cir. 1986 ); Environmental Designs, Ltd. V. Union Oil Co., 713 F.2d 693, 696, 218 USPQ 865, 868 (Fed. Cir. 1983).

"A person of ordinary skill in the art is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton." KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. ___, ___, 82 USPQ2d 1385, 1397 (2007). "[I]n many cases a person of ordinary skill will be able to fit the teachings of multiple patents together like pieces of a puzzle." Id. Office personnel may also take into account "the inferences and creative steps that a person of ordinary skill in the art would employ." Id. at ___, 82 USPQ2d at 1396. Ex parte Hiyamizu, 10 USPQ2d 1393, 1394 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1988) (The Board disagreed with the examiner's definition of one of ordinary skill in the art (a doctorate level engineer or scientist working at least 40 hours per week in semiconductor research or development), finding that the hypothetical person is not definable by way of credentials, and that the evidence in the application did not support the conclusion that such a person would require a doctorate or equivalent knowledge in science or engineering.).

References which do not qualify as prior art because they postdate the claimed invention may be relied upon to show the level of ordinary skill in the art at or around the time the invention was made. Ex parte Erlich, 22 USPQ 1463 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1992). Moreover, documents not available as prior art because the documents were not widely disseminated may be used to demonstrate the level of ordinary skill in the art. For example, the document may be relevant to establishing "a motivation to combine which is implicit in the knowledge of one of ordinary skill in the art." National Steel Car Ltd. v. Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd., 357 F.3d 1319, 1338, 69 USPQ2d 1641, 1656 (Fed. Cir. 2004)(holding that a drawing made by an engineer that was not prior art may nonetheless "be used to demonstrate a motivation to combine implicit in the knowledge of one of ordinary skill in the art").

II. SPECIFYING A PARTICULAR LEVEL OF SKILL IS NOT NECESSARY WHERE THE PRIOR ART ITSELF REFLECTS AN APPROPRIATE LEVEL

If the only facts of record pertaining to the level of skill in the art are found within the prior art of record, the court has held that an invention may be held to have been obvious without a specific finding of a particular level of skill where the prior art itself reflects an appropriate level. Chore-Time Equipment, Inc. v. Cumberland Corp., 713 F.2d 774, 218 USPQ 673 (Fed. Cir. 1983). See also Okajima v. Bourdeau, 261 F.3d 1350, 1355, 59 USPQ2d 1795, 1797 (Fed. Cir. 2001).

III. ASCERTAINING LEVEL OF ORDINARY SKILL IS NECESSARY TO MAINTAIN OBJECTIVITY

"The importance of resolving the level of ordinary skill in the art lies in the necessity of maintaining objectivity in the obviousness inquiry." Ryko Mfg. Co. v. Nu-Star, Inc., 950 F.2d 714, 718, 21 USPQ2d 1053, 1057 (Fed. Cir. 1991). The examiner must ascertain what would have been obvious to one of ordinary skill in the art at the time the invention was made, and not to the inventor, a judge, a layman, those skilled in remote arts, or to geniuses in the art at hand. Environmental Designs, Ltd. v. Union Oil Co., 713 F.2d 693, 218 USPQ 865 (Fed. Cir. 1983), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 1043 (1984).

Here is what I get from that list, the factors to keep in mind, and I know some of you are lawyers, so if you think I've missed something, sing out:

1. Were you working in the field at the time of the invention and was your educational level what is normally found?

2. If you were not working in the field at the time, can you discern from prior art found what the ordinary person skilled in the art at the time clearly did know?

3. Unlike finding prior art, with obviousness, you can use bits and pieces from various sources and show how a person of ordinary skill could pull them all together into the patent you are trying to show is obvious. So if you have four claims in a patent, you can find one claim from four different previously issued patents, and it counts. You don't have to find all four in just one previously issued patent.

4. Ordinary means exactly that. If something is obvious to you, but only because you are a genius, your opinion isn't of use, unless everyone in your field has to be a genius to be working in the field.

5. It doesn't help to just say some patent is obvious. You have to supply the reason *why* you believe it is, and how you qualify as an ordinary person skilled in the art. That such and such a person or a company was doing it already, or many such, speaks to prior art. But it also can speak to obviousness, although it is a little more amorphous. Is the problem solved by the patent so simple as to be ridiculously easy to solve? Also, is the prior art you've found such that the next step is made obvious?

6. If you find patents or papers that are around the general time period as the patent but are not technically prior art, due to the dates, can still matter when proving what a person having ordinary skill in the art would know.

7. The examiner at the USPTO has to try to figure out what an ordinary person skilled in the art would know, and then a court figures out if he got it right or not, and as we've observed from the results, they are not consistently good at this. So why not help them? Education is never a waste.

Obviousness is exactly what lawyers and USPTO examiners do not know from personal knowledge. They have to rely on someone or something external to themselves to figure out whether something is or is not obvious, or more exactly whether it would have been to someone with ordinary skill in the art at the time. Maybe if we are careful to explain the why of it, it can at least prompt lawyers defending someone accused of infringement to realize that he may have an obviousness defense he hadn't thought of, if we point it out effectively, with specificity, keeping the above factors in mind.

What Is Required to Prove a Patent is Obvious?

What's the difference between knocking out a patent by finding prior art and doing so by showing it is obvious? We need to know so we know when we find results that will work. I had no clear idea so I asked a couple of attorneys who understand patent law. Mark Webbink, who does Groklaw with me, has experience running the Peer to Patent Project, so he explained the difference like this: The claim will only be found invalid under Section 102 (novelty)

if a single item of prior art contains all of the elements of the claim

in question (it can, of course, contain more elements than the claim in

question, but it must contain at least all of the elements of the claim

in question.

Similarly, the claim will only be found invalid under Section 103

(obviousness) if some combination of items of prior art, when combined,

contain all of the elements of the claim in question and it would have

been obvious to a PHOSITA, at the time of claimed invention, to create

such a combination.

Michael Risch explained another detail in finding prior art:To answer your question, to anticipate under 102, you must have prior art with every element of the claim. You don't invalidate a patent -- you only invalidate a claim. So some claims might be invalid, while other, narrower claims are valid. But you have to have the elements of whatever claim you want to invalidate all in one document to be bulletproof (there is some leeway if you incorporate by reference, for example). You can use two different references to invalidate two different claims. So if there are two claims to a patent, the ideal is to find prior art with all the elements of the claims, but you can use one prior art reference that covers all the elements of claim one to knock out that claim, and then look for another reference that anticipated all the elements of claim two to knock out the other. But perfection is to find all the elements of all the claims in one prior art reference. This is law, so I'm guessing that, as usual, there are plenty of footnotes that could be added, but that is the overview. It's enough to know how to evaluate what you may find when using the new tool. You can find more resources on Groklaw's Patents page, including links to the law itself, if you want to dig a bit more and review what the various sections of patent law, like Section 102 and 103, say. Also, law doesn't stand still in the US system, which is case-law based. And for sure there's always plenty of patent infringement lawsuits to add to the database. In addition, patent law was recently revised. But we do have all we need to try out the new tool.

A Brief Word About Utility and Enablement

The thing about software patents is that they are written carefully to be as broad as possible, meaning sometimes without really revealing much specificity, in my experience. Filers don't even have to offer the source code, which would really help someone else to reproduce the invention. If you read a patent and have no idea what it is saying to do, then as a person with ordinary skill in the art, you can say so. It matters too. I think it would matter more if more people told the lawyers and the USPTO that you can't use the invention without a lot of experimentation to try to figure out what it is saying. I suspect more software patents could be revealed as invalid, if there was more education on this topic. So do look for that, and tell when you qualify as a PHOSITA in the field the patent is supposedly useful for that it isn't useful or can't be used, because it lacks the specifics that would make it possible to use it.

[ Update: I thought you'd find it interesting to see the jury instructions [PDF] on these topics from the Apple v. Samsung trial:

FINAL JURY INSTRUCTION NO. 30

UTILITY PATENTS—WRITTEN DESCRIPTION REQUIREMENT

A utility patent claim is invalid if the patent does not contain an adequate written description of the claimed invention. The purpose of this written description requirement is to demonstrate that the inventor was in possession of the invention at the time the application for the patent was filed, even though the claims may have been changed or new claims added since that time. The written description requirement is satisfied if a person of ordinary skill in the field reading the original patent application at the time it was filed would have recognized that the patent application described the invention as claimed, even though the description may not use the exact words found in the claim. A requirement in a claim need not be specifically disclosed in the patent application as originally filed if a person of ordinary skill would understand that the missing requirement is necessarily implied in the patent application as originally filed.

FINAL JURY INSTRUCTION NO. 31

UTILITY PATENTS—ANTICIPATION

A utility patent claim is invalid if the claimed invention is not new. For the claim to be invalid because it is not new, all of its requirements must have existed in a single device or method that predates the claimed invention, or must have been described in a single previous publication or patent that predates the claimed invention. In patent law, these previous devices, methods, publications or patents are called “prior art references.” If a patent claim is not new we say it is “anticipated” by a prior art reference.

The description in the written reference does not have to be in the same words as the claim, but all of the requirements of the claim must be there, either stated or necessarily implied, so that someone of ordinary skill in the field looking at that one reference would be able to make and use the claimed invention.

Here is a list of the ways that either party can show that a patent claim was not new:

– If the claimed invention was already publicly known or publicly used by others in the United States before the date of conception of the claimed invention;

– If the claimed invention was already patented or described in a printed publication anywhere in the world before the date of conception of the claimed invention. A reference is a “printed publication” if it is accessible to those interested in the field, even if it is difficult to find;

– If the claimed invention was already made by someone else in the United States before the date of conception of the claimed invention, if that other person had not abandoned the invention or kept it secret;

If the patent holder and the alleged infringer dispute who is a first inventor, the person who first conceived of the claimed invention and first reduced it to practice is the first inventor. If one person conceived of the claimed invention first, but reduced to practice second, that person is the first inventor only if that person (a) began to reduce the claimed invention to practice before the other party conceived of it, and (b) continued to work diligently to reduce it to practice. A claimed invention is “reduced to practice” when it has been tested sufficiently to show that it will work for its intended purpose or when it is fully described in a patent application filed with the PTO.

– If the claimed invention was already described in another issued U.S. patent or published U.S. patent application that was based on a patent application filed before the patent holder’s application filing date or the date of conception of the claimed invention.

Since certain of them are in dispute, you must determine dates of conception for the claimed inventions and prior inventions. Conception is the mental part of an inventive act and is proven when the invention is shown in its complete form by drawings, disclosure to another, or other forms of evidence presented at trial....

FINAL JURY INSTRUCTION NO. 33

UTILITY PATENTS—OBVIOUSNESS

Not all innovations are patentable. A utility patent claim is invalid if the claimed invention would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the field at the time of invention. This means that even if all of the requirements of the claim cannot be found in a single prior art reference that would anticipate the claim or constitute a statutory bar to that claim, a person of ordinary skill in the field who knew about all this prior art would have come up with the claimed invention.

The ultimate conclusion of whether a claim is obvious should be based upon your determination of several factual decisions.

First, you must decide the level of ordinary skill in the field that someone would have had at the time the claimed invention was made. In deciding the level of ordinary skill, you should consider all the evidence introduced at trial, including:

(1)

the levels of education and experience of persons working in the field;

(2) the types of problems encountered in the field; and

(3) the sophistication of the technology.

Second, you must decide the scope and content of the prior art. The parties disagree as to whether certain prior art references should be included in the prior art you use to decide the validity of claims at issue. In order to be considered as prior art to a particular patent at issue here, these references must be reasonably related to the claimed invention of that patent. A reference is reasonably related if it is in the same field as the claimed invention or is from another field to which a person of ordinary skill in the field would look to solve a known problem.

Third, you must decide what differences, if any, existed between the claimed invention and the prior art.

Finally, you should consider any of the following factors that you find have been shown by the evidence:

(1) commercial success of a product due to the merits of the claimed invention;

(2) a long felt need for the solution provided by the claimed invention;

(3) unsuccessful attempts by others to find the solution provided by the claimed invention;

(4) copying of the claimed invention by others;

(5) unexpected and superior results from the claimed invention;

(6) acceptance by others of the claimed invention as shown by praise from others in the field or from the licensing of the claimed invention; and

(7) independent invention of the claimed invention by others before or at about the same time as the named inventor thought of it.

The presence of any of factors 1-6 may be considered by you as an indication that the claimed invention would not have been obvious at the time the claimed invention was made, and the presence of factor 7 may be considered by you as an indication that the claimed invention would have been obvious at such time. Although you should consider any evidence of these factors, the relevance and importance of any of them to your decision on whether the claimed invention would have been obvious is up to you.

A patent claim composed of several elements is not proved obvious merely by demonstrating that each of its elements was independently known in the prior art. In evaluating whether such a claim would have been obvious, you may consider whether the alleged infringer has identified a reason that would have prompted a person of ordinary skill in the field to combine the elements or concepts from the prior art in the same way as in the claimed invention. There is no single way to define the line between true inventiveness on the one hand (which is patentable) and the application of common sense and ordinary skill to solve a problem on the other hand (which is not patentable). For example, market forces or other design incentives may be what produced a change, rather than true inventiveness. You may consider whether the change was merely the predictable result of using prior art elements according to their known functions, or whether it was the result of true inventiveness. You may also consider whether there is some teaching or suggestion in the prior art to make the modification or combination of elements claimed in the patent. Also, you may consider whether the innovation applies a known technique that had been used to improve a similar device or method in a similar way. You may also consider whether the claimed invention would have been obvious to try, meaning that the claimed innovation was one of a relatively small number of possible approaches to the problem with a reasonable expectation of success by those skilled in the art. However, you must be careful not to determine obviousness using the benefit of hindsight; many true inventions might seem obvious after the fact. You should put yourself in the position of a person of ordinary skill in the field at the time the claimed invention was made and you should not consider what is known today or what is learned from the teaching of the patent.

- End Update.]

Using the New Tool to Search for Prior Art

Let's now give the new Google Prior Art Finder a whirl, and I'll show you where you come in. Only you can do all the steps, in that after you find the results with the tool, you need to analyze them, but I'll get you started by explaining how the tool itself works. We'll now be looking at the novelty element, and that means searching for prior art.

Here's what I did. I put the full number of the Lodsys '908 patent into plain Google Patent Search, 5,999,908 (the other Lodsys patents are 7,133,834, 7,222,078, and 7,620,565). I chose the top result, the '908 patent itself. When you get to that page, look for a blue box at the top that says "Find prior art". That's the Prior Art Finder tool. Click it. You'll see this at the top of the page:

As you can see, the results include papers and other prior art, not just patents filed previously. The default results are Top Ten. But you can find more results if you go to Google Scholar for papers and books or to just Patents, if you want to search that way, and note that there are more results in Patents than just in the Top 10. Many more. That's why you need to narrow it down by your search terms.

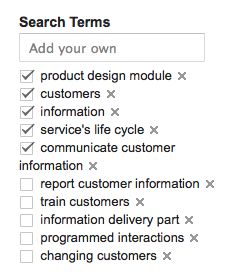

You can also play with search terms, and this is where your skill comes into play:

You can see the search terms Google used to come up with the results you see, but you can try to narrow it down and fine tune it. Patents are not found invalid by prior art. Claims are, one by one, as Michael explained. So you look to see what the claims are. What is necessary in the patent claims? If you look in the specification when the applicant discusses

how this invention differs from prior inventions, i.e., the improvement

it provides, you can usually narrow the claims down to what the inventor thinks is importantly different from prior art. The discussion will tend to indicate what elements

previously existed and how this claim differs from those previously

existing elements. So make a list. If there are four of these necessary elements, those would be your ideal search terms. The idea is to try to narrow things down to just what you are looking for, so you get fine-tuned results.

You can also change the dates. It's set already for the end date, that being the priority date of the patent you are researching, and you can narrow how far back you want to go, I suppose, but why would you? The lawyer who does the website Gametime IP immediately saw the Google Prior Art tool as a handy way to craft more ways to tighten the noose with patents. He suggests using it, by changing the date, to find infringement after the patent issued, but I suspect that won't work well, in that presumably the USPTO already did that searching before issuing other patents. Then again, maybe not so well. His graphics are good on using the tool, even if his bias against Google is offensive and his purpose not ours. He compares Google's blogpost last year on the coordinated attacks on Android with patents, many of which should not have issued, to "disdain for intellectual property owners," which reflects on his bias, not to mention his logic skills. Patents are not supposed to be used anticompetitively, just as a reminder. They are supposed to encourage innovation, not stifle it. And pointing out that patent law could be improved isn't showing disdain for IP owners; if it were then the recent changes in patent law would also have been showing similar disdain.

Using the Prior Art Tool to Compare the Lodsys Patents with Oracle's Prior Art Lists

Here's the list of prior art that Oracle found and told the court about already for the '908 patent, so then you can just eyeball that list and see if the tool has already found something that Oracle doesn't already have listed:

U.S. Patent No. 4,245,245 (“Matsumoto”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,546,382 (“McKenna”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,345,315 (“Cadotte”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,567,359 (“Lockwood”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,689,619 (“O’Brien, Jr.”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,740,890 (“William”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,816,904 (“McKenna”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,829,558 (“Welsh”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,862,268 (“Campbell”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,893,248 (“Pitts”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,973,952 (“Malec”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,912,552 (“Allison, III”),

U.S. Patent No. 4,992,940 (“Dworkin”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,001,554 (“Johnson”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,003,384 (“Durden”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,029,099 (“Goodman”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,036,479 (“Prednis”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,056,019 (“Schultz”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,065,338 (“Phillips”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,077,582 (“Kravette”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,083,271 (“Thacher”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,117,354 (“Long”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,138,377 (“Smith”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,207,784 (“Schwartzendruber”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,237,157 (“Kaplan”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,282,127 (“Mii”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,283,734 (“Von Kohorn”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,291,416 (“Hutchins”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,335,048 (“Takano”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,347,449 (“Meyer”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,347,632 (“Filepp”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,477,262 (“Banker”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,496,175 (“Oyama”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,740,035 (“Cohen”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,956,505 (“Manduley”)

JP H2-65556 (“Kita”)

JP-03-064286-A (“Garza”)

JP H3-80662 (“Ukegawa”)

JP S60-200366 (“Tanaka”)

and JP S62-280771 (“Furukawa”)

As you can see, if you looked in the Patents tab on the '908 patent page, there are results that do not appear on the Oracle list. But you have to check something. The first one in the results, for example, is patent number 5442759, an IBM patent, applied for in 1992 and issued in 1995, and that's not on Oracle's list. But be careful. If you check the Citations listed for this patent, there you find Lodsys's '908 patent listed. So this one is no good. It is prior art, but the inventor listed it as such, but his invention, it was believed, is distinguishable from it. As you see, just like Google Search, you still have to do your part of the work. But it surely found the right stuff to begin your work. It might be useful to go down that entire list of citations, actually, and use the Prior Art Finder on them too, if you were seriously looking for prior art. And my point in explaining all of it, not just the prior art part, is so you don't discard something useful otherwise. Just because something isn't prior art, it doesn't mean it can't be used for obviousness, in other words, or in some other way on the list of requirements.

Of course, as is obvious by now, you'd have to have someone, lawyers and folks like you, read the Lodsys patent and the ones on the list of newly found possible prior art, to see if they match perfectly, claim by claim, but there is no doubt that there are new entries on the list on the Google Prior Art Finder. Shout out to Oracle! Take a look.

They probably already are.

Wouldn't you be?

And in case you want to play too, and I hope you do, here's the rest of the prior art that Oracle found on the other three patents so you can compare them with what the Google Prior Art Finder finds.

For the '834 patent, Oracle found this prior art:

U.S. Patent No. 4,245,245 (“Matsumoto”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,546,382 (“McKenna”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,345,315 (“Cadotte”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,567,359 (“Lockwood”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,689,619 (“O’Brien, Jr.”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,740,890

(“William”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,816,904 (“McKenna”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,829,558 (“Welsh”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,862,268 (“Campbell”), U.S. Patent No. 4,893,248 (“Pitts”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,973,952 (“Malec”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,912,552 (“Allison, III”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,992,940 (“Dworkin”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,001,554 (“Johnson”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,003,384 (“Durden”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,029,099 (“Goodman”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,036,479 (“Prednis”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,056,019 (“Schultz”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,065,338 (“Phillips”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,077,582 (“Kravette”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,083,271 (“Thacher”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,117,354 (“Long”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,138,377 (“Smith”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,207,784 (“Schwartzendruber”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,237,157 (“Kaplan”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,282,127 (“Mii”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,283,734 (“Von Kohorn”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,291,416 (“Hutchins”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,335,048 (“Takano”), U.S. Patent No. 5,347,449 (“Meyer”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,347,632 (“Filepp”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,477,262 (“Banker”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,496,175 (“Oyama”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,740,035 (“Cohen”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,956,505 (“Manduley”)

JP H2-65556 (“Kita”)

JP-03-064286-A (“Garza”), JP H3-80662 (“Ukegawa”)

JP S60-200366 (“Tanaka”)

JP S62-280771 (“Furukawa”)

And here's Oracle's findings for Lodsys patent number '708:

U.S. Patent No. 4,245,245 (“Matsumoto”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,546,382 (“McKenna”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,345,315 (“Cadotte”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,567,359 (“Lockwood”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,689,619 (“O’Brien, Jr.”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,740,890 (“William”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,816,904 (“McKenna”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,829,558 (“Welsh”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,862,268 (“Campbell”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,893,248 (“Pitts”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,973,952 (“Malec”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,912,552 (“Allison, III”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,992,940 (“Dworkin”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,001,554 (“Johnson”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,003,384 (“Durden”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,029,099 (“Goodman”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,036,479 (“Prednis”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,056,019 (“Schultz”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,065,338 (“Phillips”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,077,582 (“Kravette”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,083,271 (“Thacher”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,117,354 (“Long”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,138,377 (“Smith”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,207,784 (“Schwartzendruber”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,237,157 (“Kaplan”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,282,127 (“Mii”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,283,734 (“Von Kohorn”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,291,416 (“Hutchins”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,335,048 (“Takano”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,347,449 (“Meyer”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,347,632 (“Filepp”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,477,262 (“Banker”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,496,175 (“Oyama”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,740,035 (“Cohen”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,956,505 (“Manduley”)

JP H2-65556 (“Kita”)

JP-03-064286-A

(“Garza”)

JP H3-80662 (“Ukegawa”)

JP S60-200366 (“Tanaka”)

JP S62-280771 (“Furukawa”)

And finally, here's what Oracle found for Lodsys patent number '565:

U.S. Patent No. 4,245,245 (“Matsumoto”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,546,382 (“McKenna”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,345,315 (“Cadotte”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,567,359 (“Lockwood”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,689,619 (“O’Brien, Jr.”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,740,890 (“William”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,816,904 (“McKenna”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,829,558 (“Welsh”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,862,268 (“Campbell”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,893,248 (“Pitts”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,973,952 (“Malec”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,912,552 (“Allison, III”)

U.S. Patent No. 4,992,940 (“Dworkin”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,001,554 (“Johnson”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,003,384 (“Durden”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,029,099 (“Goodman”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,036,479 (“Prednis”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,056,019 (“Schultz”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,065,338 (“Phillips”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,077,582 (“Kravette”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,083,271 (“Thacher”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,117,354 (“Long”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,138,377 (“Smith”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,207,784 (“Schwartzendruber”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,237,157 (“Kaplan”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,282,127 (“Mii”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,283,734 (“Von Kohorn”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,291,416 (“Hutchins”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,335,048 (“Takano”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,347,449 (“Meyer”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,347,632 (“Filepp”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,477,262 (“Banker”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,496,175 (“Oyama”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,740,035 (“Cohen”)

U.S. Patent No. 5,956,505 (“Manduley”)

JP H2-65556 (“Kita”)

JP-03-064286-A (“Garza”)

JP H3-80662 (“Ukegawa”)

JP S60-200366 (“Tanaka”)

JP S62-280771 (“Furukawa”).

That's as far as I can take you. The rest is up to you.

If you find anything that looks really on point, do sing out. And if any Googlers out there know of more ways to make the tool useful, please say so in a comment. We want to get this right. The Lodsys patents are quite old, and that makes them particularly hard to find prior art for. Let's see what the tool can do.

Google says that it will be refining the tool, and I already have a suggestion: would it be possible to set it up so the claims in the various patents are available as plain text? It would greatly help to be able to copy and paste them, so as to have them more easily available when searching for prior art. If you have other suggestions, do say so.

|

|

|

|

| Authored by: Anonymous on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 09:13 AM EDT |

| This is very very useful. I am already busy with it so watch this space.

Question is:

Would any of the patents Apple is wielding against

Android survive? [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: nsomos on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 09:31 AM EDT |

Please post corrections in this thread.

Summaries in the title may be helpful.

Thanks[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: bugstomper on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 09:35 AM EDT |

Please type the title of the News Picks article in the Title box of your

comment, and include the link to the article in HTML Formatted mode for the

convenience of the readers after the article has scrolled off the News Picks

sidebar.

Hint: Avoid a Geeklog bug that posts some links broken by putting a space on

either side of the text of the link, as in

<a href="http://example.com/foo"> See the spaces? </a>

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: bugstomper on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 09:41 AM EDT |

Please stay off topic in these threads. Use HTML Formatted mode to make your

links nice and clickable.

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: bugstomper on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 10:34 AM EDT |

| Please post your transcriptions of Comes exhibits here with full HTML markup but

posted in Plain Old Text mode so PJ can copy and paste it

See the Comes

Tracking Page to find and claim PDF files that still need to be

transcribed.

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: bugstomper on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 10:53 AM EDT |

PJ said, "would it be possible to set it up so the claims in the various

patents are available as plain text? It would greatly help to be able to copy

and paste them"

When I look at patents in Google Patents, the claims are in text and I can copy

and paste them. This is in both Firefox and Chrome without any special

extensions. For example, when I go to this link for US Patent 5,999,908 which I

go to by searching for 5,999,908 in the Google Patent search:

http://www.google.com/patents?id=uNsYAAAAEBAJ

Do you see the claims as an image or as text there?

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 12:29 PM EDT |

Interesting, but it needs some fine tuning. I found that it sometimes

includes in the results patents that were cited in the application, and so have

already been considered and found by the examiner not to be invalidating prior

art. [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 01:34 PM EDT |

"Lots of things are obvious after the fact, but that doesn't count."

Ya. Round corners are only obvious after the fact.

This "lots of things are obvious after the fact" is a get out of jail

free card for companies that want to patent obvious stuff. The corrupt

officials at the patent office and the corrupt judges on the CAFC can use this

to dismiss any claim of obviousness, no matter how silly.

The whole business of patents is corrupt and evil.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Tufty on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 02:12 PM EDT |

If Oracle are using Google's search tool.

As for obviousness, most patents we seem to be covering here fall flat on their

faces on this one.

---

Linux powered squirrel.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 02:21 PM EDT |

"According to the Court, the laws of nature, physical

phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable. The

relevant distinction between patentable and unpatentable

subject matter is between products of nature, living or not,

and human-made."

So, patents on human genes should be all disallowed, right?

After all, they are products of nature... Now that we can

construct our own genes, I'd grant that is another thing

entirely, maybe.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 02:28 PM EDT |

"A person of ordinary skill in the art is also a person of

ordinary creativity, not an automaton."

What about a person of extra-ordinary skill in the art? What

if the "invention" is obvious to them? How do you define

"ordinary skill in the art" anyway?

I am considered by my peers as a person of more than

ordinary skill in the art of computer software engineering -

I even have a patent to prove it, and after using the Google

patent search tool to verify it, no one else has come close

to what I got the patent for, at least before I got the

patent. Unfortunately, I am only the (sole) inventor, not

the owner, of the patent, and the owner hasn't seen fit to

sue others for violating their patent rights (Microsoft and

Oracle primarily). So, what is obvious to me, may not be

obvious to most software developers / engineers.

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 04:05 PM EDT |

> You have to supply the reason *why* you believe it is, and how you qualify

as an ordinary person skilled in the art.

So who's gonna stand up and say, hey, I'm an ordinary person, nothing genius

about me? Especially in a high interest public case :)[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: IMANAL_TOO on Sunday, August 19 2012 @ 11:52 PM EDT |

Rounded corners are not only obvious, but trivial. They have been implemented as

a standard feature in major vector drawing programs for many years. Here some

examples:

Inkscape (02-01-2007)

http://web.archive.org/web/20070102234025/http://tavmjong.free.fr/INKSCAPE/MANUA

L/html/Shapes-Rectangles.html

Adobe Illustrator (06-06-2003)

http://board.flashkit.com/board/showthread.php?t=460192

AutoCAD (17-06-2006)

http://www.cadtutor.net/forum/showthread.php?8574-Rounding-edges

Who could say anything but that it is blatantly trivial using one of the most

obvious function in a graphics package if you design something...

The functions did not arrive because they got inspired by that telephone of

Apple, the functions were there long before... The mentally retarded aren't born

that way because their parents saw a telephone designed by Apple; there are

other causes than Apple in the world.

---

______

IMANAL

.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: pem on Monday, August 20 2012 @ 10:39 AM EDT |

CREDIT CARDS are rounded rectangles.

It would be absolutely GREAT, during closing arguments, for a Samsung attorney

to whip out his wallet and explain how difficult life would be if you had to

line up your credit card really carefully every time you put it back in the

wallet, and if it kept pricking your fingers every time you pulled it out.

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

|

|

|