|

|

| Oracle v. Google - Trial On; Most of Cockburn Third Report Stricken |

|

|

Tuesday, March 13 2012 @ 11:35 PM EDT

|

Judge Alsup is ready to get on with it, and to that end he has set this case for trial beginning April 16, 2012. (786 [PDF; Text]) He is anticipating an eight week trial, which will be brutal on the jurors. To that end the potential jurors will be pre-cleared to assure their availability. The judge has also asked Google to withdraw those invalidity arguments it has asserted in reexamination that have not been adopted by the USPTO. Clearly, he does not want to hear them.

What set the stage for the trial to move forward was the Court's decision on Dr. Cockburn's third attempt at a damages report. (785 [PDF; Text]) And like they say in baseball, "Strike three!" Actually, the Court did not reject all of the third attempt, simply most of it and certainly all of the parts of it that most troubled Google.

Stricken are:

- the independent-significance approach to valuation;

- the econometric analysis;

- the conjoint analysis as used to determine market share; and

- the "upper bound" calculation in the group-and-value approach.

What remains? Dr. Cockburn will be able to refer to the conjoint analysis for determination of the relative importance between application startup time and availability of applications. He will also be able to rely on the "lower bound" calculation in the group-and value approach, although the court has directed that this "lower bound" be reduced by $37 million for the unasserted copyrights. That leaves a total value of all copyrights in suit and all 569 patents in Sun's Java mobile patent portfolio at $561 million, which amount is to be split equally between the copyrights and patents. In other words, the total damages for past infringement cannot exceed that number absent a finding of wilfullness. It remains to be determined what portion the patent half will be allocated to each of the asserted patents.

In an important step back from his prior position, Judge Alsup has concluded that Oracle does not need to allocate the patent damages on a claim by claim basis, only on a patent by patent basis. That is the bad news for Google. The good news is that Google may now be able to knock out all damages from each of the patents on the marking issue.

One of the funnier lines in the order is the judge's reaction to an equation contained in the Cockburn report. The judge had this to say:

The reader may well reel in disbelief at this equation and wonder how the judge could let

it be presented to the jury. While it is sui generis [unique] and will not be found in the textbooks, the equation is merely an arithmetical statement of the components previously allowed, such as the

assumption that the 2006 value of the copyrights in suit would have been half the 2006 value of

the six patents in suit. The jury may well raise a skeptical brow over the seemingly convoluted

testimony but that is not the test for Daubert.

There are issues yet to be resolved. One of the important issues is whether the hypothetical 2006 license between Sun and Google was a perpetual license or a three-year license. Amazingly, neither of the parties seemed to be certain on this point at the March 7 hearing. They had better be prepared to address it at trial.

Another is the fact that, despite all of these efforts by Dr. Cockburn, no value has been assigned to the '520 patent. That remains to be figured out, and the judge has asked the parties to have their recommendations on that point to him by March 19.

Let the games begin!

**************

Docket

03/13/2012 - 785 - ORDER

GRANTING IN PART AND DENYING IN PART GOOGLE'S DAUBERT MOTION TO EXCLUDE

DR. COCKBURN'S THIRD REPORT by Hon. William Alsup granting in part and

denying in part 718 Motion to Strike.(whalc1, COURT STAFF) (Filed on

3/13/2012) (Entered: 03/13/2012)

03/13/2012 - 786 - ORDER

SETTING TRIAL DATE OF APRIL 16, 2012 re 675 Order. Signed by Judge Alsup

on March 13, 2012. (whalc1, COURT STAFF) (Filed on 3/13/2012) (Entered:

03/13/2012)

03/13/2012 - 787 - REQUEST

AND NOTICE RE DR. JAMES KEARL re 413 Order. Signed by Judge Alsup on

March 13, 2012. (whalc1, COURT STAFF) (Filed on 3/13/2012) (Entered:

03/13/2012)

03/13/2012 - 788 - NOTICE RE

TRIAL MATERIALS. Signed by Judge Alsup on March 13, 2012. (whalc1, COURT

STAFF) (Filed on 3/13/2012) (Entered: 03/13/2012)

**************

Documents

785

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.,

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.,

Defendant.

No. C 10-03561 WHA

ORDER GRANTING IN PART

AND DENYING IN PART

GOOGLE'S DAUBERT

MOTION TO EXCLUDE

DR. COCKBURN'S THIRD

REPORT

INTRODUCTION

In this patent and copyright infringement action involving Java and Android, defendant challenges plaintiff's third damages expert report. For the following reasons, the motion is GRANTED IN PART and DENIED IN PART.

STATEMENT

Two previous damages reports for plaintiff have been stricken. The first order dated July 22, 2011, rejected Dr. Ian Cockburn's damages report for failing to apportion the value of the asserted claims and instead using the total value of Java and Android in calculating damages, among other reasons (Dkt. No. 230). The second order dated January 9, 2012, partially excluded his revised damages report for using a flawed apportionment methodology, among other reasons (Dkt. No. 685). In his latest damages report, Dr. Cockburn advances new apportionment methodologies.

First, Dr. Cockburn starts with Sun's February 2006 demand of $99 million to defendant Google Inc. Second, he upwardly adjusts by $557 million to account for lost convoyed sales Sun projected to make through its licensing partnership with Google. Third, he adds $28 million by removing a revenue-sharing cap, resulting in a subtotal of $684 million. This is the pie he then apportions between the intellectual property in suit and the intellectual property not in suit. Fourth, he allocates part of this number to the patents and copyrights in suit, using two alternative methodologies — the so-called "group and value" and "independent significance" approaches (Rpt ¶¶ 37-68). Based on these alternative apportionment methodologies, reasonable royalties for patents and copyrights in suit, through the end of 2011, are (1) between $70 and $224 million under the group-and-value approach, and (2) at least $171 million under the independent-significance approach. Fifth, he downwardly adjusts for extraterritorial infringement, failure to mark, and non-accused devices. With all the downward adjustments subtracted, Dr. Cockburn calculates patent damages to be between $18 and $57 million, and a copyright lost license fee to be between $35 and $112 million.

Unchanged from his second damages report, Dr. Cockburn calculates copyright lost profits to be $136 million and copyright disgorgement to be $824 million (not accounting for non- infringing apportionment, which step Google has the burden to prove). Thus, without reductions to copyright disgorgement, Dr. Cockburn calculates total damages to be approximately one billion dollars through the end of 2011.

Google moves to strike Dr. Cockburn's latest report under Daubert. This order follows briefing and a hearing.

ANALYSIS

An expert witness may provide opinion testimony "if (1) the testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data, (2) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods, and (3) the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case." FRE 702. District courts thus "are charged with a 'gatekeeping role,' the objective of which is to ensure that expert testimony admitted into evidence is both reliable and relevant." Sundance, Inc. v. DeMonte Fabricating Ltd., 550 F.3d 1356, 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

2

1. GROUP-AND-VALUE APPROACH.

One method advanced by Dr. Cockburn for calculating reasonable royalty for both patents and copyrights is the so-called group-and-value approach. Under this approach, Dr. Cockburn first identifies the components that would have been licensed from Sun to Google in the 2006 bundle. This would have included a license to Sun's Java mobile patents and copyrights, promotion of the Java brand and trademark, and the benefit of Sun's engineering resources in developing Android (Rpt ¶ 338).

Dr. Cockburn first apportions the 2006 licensing fee and lost convoyed sales ($684 million) downward by $86 million to account for projected engineering expenses Sun would have incurred through its licensing partnership with Google, leaving $598 million (Rpt ¶ 48). Then, based on a qualitative patent ranking by Oracle engineers and a published study generally regarding the distribution of patent values, he concludes that the six patents in suit are worth somewhere between 10.2% and 32.7% of the total Java mobile patent portfolio ($70 and $224 million). Based on Dr. Steven Shugan's conjoint analysis, which had suggests that consumers value the availability of applications (enabled by the asserted copyrights) approximately half as much as application speed (enabled by the asserted patents) in smartphones, Dr. Cockburn sets the value of the asserted copyrights at half the value of the asserted patents (Rpt ¶¶ 6, 54). With all the relative values in place, Dr. Cockburn allocates the adjusted starting point of $598 million between the patents in suit, copyrights in suit, and patents not in suit using an algebraic formula with only one variable to solve. These steps are now considered in detail.1

A. Ranking of Patents.

To rank the six patents in suit with all other patents in the 2006 licensing bundle, a team of Oracle engineers recently evaluated the Sun patents that would have been included in the 2006 bundle and ranked those patents based on expected technical contribution to a smartphone platform (Rpt ¶¶ 391—97). The Oracle engineers began by identifying 22 Java technology groups, such as *boot, *jit, and *interpreter, that would have been relevant to a smartphone platform in

3

2006, the time of the hypothetical negotiation (Reinhold Decl. ¶ 10). They then ranked those 22 groups by considering their importance to startup time, speed, memory and security for a smartphone platform (id. ¶ 19). So, this step identified 22 technology groups.

Separately, the engineers created a list of over 1300 patents issued to Sun prior to June 30, 2006 by filtering for patents that include the terms "Java" or "bytecode" or listed James Gosling or Nedim Fresko as an inventor. By reviewing the titles, abstracts, inventors, application dates, and where necessary, the specifications and claims, the engineers were able to evaluate which patents would have been included in the parties' 2006 smartphone platform negotiations (see, e.g., Reinhold Decl. ¶ 17; Kessler Decl. ¶ 9). This process left 569 relevant patents that would have been included in the 2006 bundle. The engineers then categorized those 569 patents into the 22 technology groups.

Next, the engineers rated the importance of each of the 569 patents on a three-point scale ("1" being most valuable), within each technology group, based on the patented functionality's expected contribution to a smartphone platform's startup, speed, or footprint (Reinhold Decl. ¶ 21). Then, Oracle engineers counted the number of patents that were in the purportedly top three technology groups (out of the aforementioned 22 non-overlapping technology groups) and had a "1" rating. This count resulted in 22 patents (to avoid confusion, the reader must appreciate that the number 22 here has no correlation with the 22 for the number of technology groups), which included three of the patents in suit. Dr. Cockburn then decided that these 22 patents were the most valuable of Sun's Java mobile patent portfolio in 2006.

In its briefs, Google argued that the Oracle engineers were biased in their ranking of the patents in the 2006 bundle. At the March 7 hearing, however, Google conceded that the issue of bias was a point for cross-examination at trial and no longer a basis for its Daubert motion.

A different concern, however, arises in Dr. Cockburn's methodology for determining the "upper bound" of the ranking, and therefore the reasonable royalty analysis. Not satisfied that three of the patents in suit were among the top 22 patents selected by Oracle engineers, Dr. Cockburn further opines that those three patents in suit — the '720, '205, and '104 patents — are the most valuable of the top 22 patents, thus propelling the three to ever higher damage

4

calculations (from $59 million to $191 million). This further "top three" ranking lacks a reliable basis and must be stricken.

Dr. Cockburn concedes that the Oracle engineers themselves were not able to differentiate (i.e., further rank) the top 22 patents in terms of value to the project (Rpt ¶ 409). Dr. Cockburn, however, opines that because Google decided to infringe those three asserted patents (for damage purposes we must presume the jury will find infringement), then those three patents must have been the most valuable in 2006. This logic is too thin to support the huge weight piled thereon. There is nothing in Dr. Cockburn's report to show that Google planned in 2006 to incorporate those particular functionalities covered by the three patents into Android. Moreover, as Dr. Cockburn himself writes elsewhere in his report, patents in a single portfolio derive value from complementing each other to prevent design around, meaning that unasserted patents are valuable because they prevent design around asserted patents (Rpt ¶ 335). In addition, Dr. Cockburn's reasoning is internally inconsistent because three other asserted patents — the '702, '520, and '476 patents — do not even rank in his top 22 patents in terms of value.

Thus, the "upper bound" of the patent ranking and the reasonable royalty calculation derived from it are STRICKEN. Specifically, Dr. Cockburn can only opine on his "lower bound" calculation, in which each patent in his top 22 has equal value to each other. The calculation of dollar values will be spelled out in the next step of the analysis.

B. Patent-Value Studies.

Building on the ranking by Oracle engineers, Dr. Cockburn performs additional steps to calculate the dollar value of the now-ranked patents. He begins by relying on three patent-value studies to estimate the relative value distribution of the now-ranked patents in the 2006 bundle. A. GAMBARDELLA, P. GIURI, AND M. MARIANI, "THE VALUE OF EUROPEAN PATENTS — EVIDENCE FROM A SURVEY OF EUROPEAN INVENTORS," FINAL REPORT OF THE PATVAL EU PROJECT, January 2005; D. HARHOFF, F. SCHERER, K. VOPEL, "CITATIONS, FAMILY SIZE, OPPOSITION AND THE VALUE OF PATENT RIGHTS," RESEARCH POLICY 32, October, 2002; J. BARNEY, "A STUDY OF PATENT MORTALITY RATES: USING STATISTICAL SURVIVAL ANALYSIS TO RATE AND VALUE PATENT ASSETS," AIPLA QUARTERLY JOURNAL, VOL. 30, NO. 3, Summer

5

2002. For his specific numerical calculation, however, Dr. Cockburn only uses numbers from the so-called PatVal study. Each of the cited studies concludes that the distribution of value among patents in the portfolios studied is highly skewed, i.e., that a handful of patents accounted for a large percentage of the value of all patents in a sample set. Based on the results of these studies, Dr. Cockburn concludes that the top 22 patents in Sun's Java mobile patent portfolio, which consisted of 569 patents in total, were worth 77.1% of the 2006 patent portfolio's overall value, and the combined value of the six patents in suit were worth between 10.2% and 32.7% (Rpt ¶¶ 408, 412, Exh. 36).

In his report, Dr. Cockburn opines that based on his experience dealing with technology licensing and his academic work, the observed value-distribution curves from the cited studies are applicable to the expected value distribution of Sun's Java mobile patent portfolio (Rpt ¶ 404, 412 fn 420). The PatVal study calculated a value-distribution curve for European patents based on approximately 10,000 survey responses from inventors covering nearly 10,000 patents across countries and technology areas. The Harhoff study was based on 394 survey responses covering 772 German patents across technology areas. And the Barney study extrapolated a lognormal distribution curve based on maintenance rates for 70,000 U.S. patents across technology areas.

Google argues that the cited studies are inapplicable to patent portfolios of a single technology company based in the United States, such as Sun in 2006. In his declaration herein, Dr. Cockburn further explains the studies' applicability to the facts of this action. Dr. Cockburn explains that the value-distribution curve of a single company's distribution would be similar to that of a broader sampling of industries and countries because the same distribution curve is seen time and time again in a variety of contexts (Cockburn Decl. ¶¶ 4—12). As support, he appends a study where the value-distribution curve of patents owned by Harvard is similar to broader country-wide sample sets of U.S. patents and German patents (Cockburn Decl. Exh. A). He also cites other studies that have also reported similar value distributions for patents limited to specific product areas (Cockburn Decl. ¶ 8). He also describes his own personal experience evaluating patent values in single portfolios where the value distribution was similar to the three studies

6

(Cockburn Decl. ¶ 9—12). Google has not submitted opposing studies to suggest otherwise. Dr. Cockburn's explanations are sufficient, for the purposes of Daubert, to rebut Google's objections.

At the hearing and in its briefs, Google objected to the fact only 569 patents were selected from many thousands then-owned by Sun as the sample set for plotting a distribution curve. Google argues that Dr. Cockburn should have applied the studies' distribution curves on all of Sun's patents, which was a much larger group. This argument will perhaps persuade the jury and it may persuade others trained in such matters but it is not enough to exclude the analysis from trial. As Dr. Cockburn and the Oracle engineers explain, the 569 patents were chosen based on an allegedly objective criteria of whether they would have been included in the 2006 bundle. Since the apportionment analysis attempts to apportion the value of the 2006 bundle, it is methodologically permissible to apply a value-distribution curve only to patents that would have been included in the 2006 bundle. Google has not shown a systemic bias in the selection of the 569 that would render the studies' distribution curves inapplicable. The selection criterion was merely relevance to smartphones, a criterion that has not been shown to misalign with the value-distribution curves.

Therefore, Dr. Cockburn can opine that the 569 patents that would have been included in the 2006 license bundle had a value-distribution curve similar to that observed in the three cited studies. Dr. Cockburn can also opine that three of the patents in suit, the '720, '205, and '104 patents, were among the 22 most valuable patents in the bundle (top four percent, calculated from 22 divided by 569) but cannot opine that those three patents were the most valuable of the 569 patents (top 0.5%, calculated from three divided by 569).

With the relative values of the 569 patents and the dollar amount of the adjusted start point, Dr. Cockburn uses an algebraic formula to calculate the dollar value of the patents. Under his "lower bound" calculation — in which, as discussed earlier, each patent in his top 22 has equal value to each other — each of the 22 top patents has a reasonable royalty of approximately $20 million (calculated by averaging or spreading evenly the total value, approximately $440 million, across the top 22 patents), before discounting for downward adjustments due to marking, non-accused devices, and extraterritorial infringement. As discussed in the previous section, Dr.

7>/p>

Cockburn can only opine on this "lower bound" calculation ($20 million per patent before offsets), and not the "upper bound" calculation.

Requiring Dr. Cockburn to use the average value of the top four percent of the patent portfolio (from the "lower bound" calculation), instead of using the extrapolated value of the top 0.5% (from the "upper bound" calculation), will largely obviate concerns of confidence interval and sample size addressed next.

C. The Court's Own Concerns Regarding the

Value-Distribution Curves from the Cited Studies.

The Court itself has raised a criticism that will now be stated if only for the record. This criticism was not joined in by Google and therefore it will not be a ground for excluding the report. Nonetheless, the reader will appreciate that this aspect of Dr. Cockburn's approach is a concern, at least to this district judge.

No one should doubt that the distribution of value in any patent portfolio will be skewed. A few patents will typically represent a disproportionate share of the overall portfolio value. This accords with the familiar 80/20 "rule of thumb" in life that twenty percent of any group accounts for eighty percent of the results. In this case, however, the issue is the extent to which the skewness is even more lop-sided than 80/20 such that a tiny part of any randomly selected portfolio represents a very high percentage of the overall value of that portfolio.

Here, Dr. Cockburn selected three portfolios studied in the literature and examined the far right "tail" of each of the three distribution curves. For the top twenty percent, the results varied only slightly, showing 94.4 percent, 90.8 percent and 98.4 percent of the overall value was in the twenty-percent segment (see Rpt Exh. 34). This is higher than the 80/20 rule of thumb but the three results were fairly close and averaged around 94 percent, so this is not the concern. By contrast, for the top one percent, the three sample portfolios varied widely: 52.6 percent, 42.1 percent, and 78.4 percent of the overall value of the three samples. When only three samples are taken and the results vary widely, our level of confidence in their predictive power is not very high. That is, we now have only three sample portfolios; what are the chances that a fourth portfolio randomly chosen will conform to the three? While it seems likely that the overall general shape of all the curves will be similar, it is only the tip of the right-hand tail that matters

8

for present purposes. For the tip of the tail — the far right one percent — the shapes vary widely among the three and there is little assurance that a fourth sample will even fall within the range of the one-percent data points associated with the three samples.

The reason that the one-percent results vary more widely seems clear — the one-percent segment deals with very few data points within each sample portfolio, so few data points in fact, that one must ask if the extreme right of the distribution curves should be disregarded as "outliers." But even if all the data points are fully credited (meaning that the outlier problem is ignored), the fact remains that they produce widely varying results as among only three sampled portfolios, a circumstance that counsels in favor of analyzing more portfolios until enough of a pattern emerges as to the one-percent segment that would allow reasonably firm conclusions to be drawn as to that tip-of-the-tail segment. Again, for the twenty-percent case, with so many more data points factored in, the results are sufficiently close that we can have confidence in the more compact range, even with only a sample of three. The opposite applies, however, to the one-percent case with correspondingly fewer data points and far more volatility in the results. This may be important in determining reliability when such large extrapolations are predicated, as here, on such a small sample size.

This problem was raised sua sponte by the Court and addressed at the March 7 hearing. Counsel for Google, however, conceded that the far right of the curve would be as suggested by Dr. Cockburn and did not adopt this criticism. The Court, therefore, will merely note the criticism for the record, lest it be said later, that this district judge approved this use of patent- value distribution curves over this reservation.

D. Patent-by-Patent Instead of Claim-by-Claim.

Dr. Cockburn's report does not break out the value of the unasserted claims of the patents in suit versus the asserted claims (Cockburn Dep. at 90). Nevertheless, this order finds that a claim-by-claim apportionment is not required under current patent law. Admittedly, this conclusion retreats from prior suggestions by the Court that apportionment should be on a claim-by-claim basis.

9

The reasonable royalty statute requires that the patentee is awarded "a reasonable royalty for the use made of the invention by the infringer." 35 U.S.C. 284 (emphasis added). Under current USPTO guidelines, there is a presumption that each issued patent contains only one independent and distinct invention. MPEP 802; see 35 U.S.C. 121, 37 C.F.R. 1.141. If each patent covers only one invention, then each claim represents merely different shades of the same invention and it is reasonable to require — in the hypothetical negotiation — that the infringer license the entire patent. Thus, Dr. Cockburn is not required to apportion damages on a claim-by-claim basis.

E. Apportionment of Unasserted Copyrights.

Google argues that Dr. Cockburn fails to adequately discount the value of unasserted copyrights. Admittedly, Dr. Cockburn does not separately evaluate unasserted copyrights, such as source code implementing the virtual machine and all class libraries not in dispute (Cockburn Dep. at 151—52). Instead, Dr. Cockburn opines that the value of all copyrighted materials other than the APIs at issue, i.e., source code, is subsumed into the $86 million reduction for Sun's projected engineering expenses because Sun engineers would have written all the necessary code for Google (Rpt ¶¶ 362—86). Put another way, Dr. Cockburn opines that Google, in 2006, would not have placed any value on Sun's source code in addition to the value of work Sun engineers would do under the 2006 licensing agreement to implement Java on Android.

Dr. Cockburn is wrong on this one. If, during a hypothetical negotiation in 2006, Sun had taken its engineering know-how off the negotiation table, then Google would have subtracted $86 million from its adjusted starting-point offer, per Dr. Cockburn's calculation. There would, however, have still been value associated with the source code and other copyrighted items that Google would have received the option to use even through Google wound up electing not to do so in the actual event.

The value of the unasserted copyrights should not be subsumed into the reduction for engineering costs. Dr. Cockburn shall adjust his group-and-value calculation by deducting $37 million, his calculated value of the unasserted copyrights, from the adjusted starting point of $598

10

million. Accordingly, $561 million shall be the total value of the copyrights in suit and 569 patents in Sun's Java mobile patent portfolio.

2. INDEPENDENT-SIGNIFICANCE APPROACH.

Dr. Cockburn advances an alternative method for calculating reasonable royalty. Under the so-called independent-significance approach, Dr. Cockburn opines that at least 25% of the 2006 licensing bundle would have been attributable to the patent claims in suit. This opinion is based on "his expertise" and (1) documents in 2006 on the importance of characteristics such as processing speed, memory, and number of applications to Android, (2) documents in 2006 on the availability of non-infringing alternatives to a Java license, (3) opinions of Oracle's technical expert on the importance of the patent claims to Android, and (4) benchmarking studies conducted in 2011 to determine the performance benefits of the patent claims on Android's performance (Rpt ¶¶ 5, 60—68; Cockburn Dep. at 135—37). The independent-significance approach does not consider the econometric study, conjoint analyses, or a breakdown of value for each component of 2006 licensing bundle (e.g., value of Oracle engineers, value of the copyrights not in suit, and value of the non-asserted patents that would have been in the 2006 license bundle) (Rpt ¶¶ 67, 325).

In rejecting Dr. Cockburn's prior attempt at apportionment, the January 9 order held, "[i]f the $100 million offer in 2006 is used as the starting point ... then a fair apportionment of the $100 million as between the technology in suit and the remainder of the technology then offered must be made." In Dr. Cockburn's latest report, the independent-significance approach makes no attempt to do so.

Instead, the independent-significance approach relies on evidence that the patents in suit would have been important to Google in 2006 to derive an apportionment of the 2006 licensing bundle, without any analysis of the remainder of technology offered in the bundle. Under this approach, Dr. Cockburn attributes at least 37.5% of the value of the 2006 offer to the patent claims and copyrights in suit, leaving no more than 62.5% percent to be spread over the many thousands of other know-how items included in the 2006 offer.

11

Just like the rejected apportionment methodology in the prior report, the fatal flaw in the independent-significance approach is that the universe of know-how included in Android during 2008—2011 was different from the universe of know-how included in the 2006 offer. The January 9 order has already explained this apples-and-oranges problem (Dkt. No. 685 at 8):

Android today undoubtedly represents some Java know-how, some technology owned by strangers to this litigation (presumably licensed), and a fair dose of Google's own engineering. The 2006 offer, in contrast, represented thousands of Java-related features, many of which never made it into Android but nonetheless would have had value. Dr. Cockburn failed to account for this disconnect.

While the evidence considered by the independent-significance approach arguably shows that the patents in suit would eventually contribute to the success of Android, the fact remains that the rest of the 2006 bundle does not bear any relationship to the rest of the Android. Reasonable parties in 2006 might well have viewed the rest of the 2006 bundle as worth far more than the patents and copyrights asserted in this action.

Oracle argues that the independent significant approach is similar to the damages methodology approved by the court of appeals in Finjan, Inc. v. Secure Computing Corp., 626 F. 3d 1197 (Fed. Cir. 2010). In that decision, the jury had found that defendant infringed three software patents related to proactive scanning (techniques for defending against computer viruses) and awarded reasonable royalty damages based on the testimony of patentee's expert. At trial, the patentee's expert had invoked the entire market value rule and opined that after (1) eliminating expenses not related to the patented functionality, such as research and development expenses for the accused product and litigation costs, and (2) relying on evidence that the patented technology was fundamentally important to the infringing product, among other factors, the proper royalty rate was between 8%—18% of infringer's actual revenue. The court of appeals upheld the damages award. Id. at 1207—12.

Finjan is inapposite to the situation here. The expert in that action derived an apportionment percentage of the infringing product's revenue after discounting non-patented value in that product, such as R&D expenses. Here, the independent-significance approach attempts to derive an apportionment percentage of the 2006 licensing bundle without discounting

12

the value of non-asserted intellectual property in that bundle. This apportionment methodology is flawed and shall be STRICKEN.

3. CONJOINT ANALYSIS.

Throughout his reasonable royalty analysis for each patent and copyright, Dr. Cockburn cites Dr. Steven Shugan's conjoint analysis for an estimate of Android's increase in market share due to infringement (see Rpt Exhs. 6—11). Moreover, in the group-and-value approach, Dr. Cockburn expressly relies on the conjoint analysis for his assumption that the copyrights in suit are worth half the value of the patents in suit. This ratio of one to two is critical to his deriving an algebraic equation to do the apportionment (as explained below).

For the conjoint analysis, Dr. Shugan used a web-based survey to measure the relative importance to consumers of seven smartphone features: application multitasking, application startup time, availability of third-party applications, mobile operating system brand, price, screen size, and voice command capabilities (Shugan Rpt at 10). The survey asked respondents to choose between side-by-side comparisons of different smartphone "profiles." Each profile was a written list of varied levels of functionality in each of the seven features — for example, one phone might be described as (1) an Android phone with (2) a 4.5-inch screen that (3) can run five apps at once (4) with a startup time of 2 seconds, (5) 300,000 available apps, and (6) voice dialing and texting (7) available for a sale price of $200. Respondents were instructed to assume that every feature other than the seven listed features remained constant (Shugan Rpt App. E at E12—E20). After collecting the respondents' selections, Dr. Shugan ran a regression analysis to determine the relative importance of each feature to overall consumer product preference. This estimate was then used by Dr. Cockburn in the group-and-value approach to allocate the value of the 2006 bundle between the patents in suit and copyrights in suit. Dr. Shugan also calculated changes in Android market share if the patented functionalities were removed. This estimate was used by Dr. Cockburn in his reasonable royalty calculations for each patent and copyright in suit.

A. Conjoint Surveys Generally.

Consumer surveys are not inherently unreliable for damages calculation. See Lucent Technologies, Inc. v. Gateway, Inc., 580 F.3d 1301, 1333—34 (Fed. Cir. 2009). Google's own

13

damages expert has written that conjoint surveys are appropriate for damages calculation in litigation (Dkt. No. 738 at Exh. I).

Google argues that Dr. Shugan's conjoint analysis is too simplistic because "if 20% of consumers value application start time more than other tested features, an increase in application start time on Android phones would mean 20% drop in Android market share" (Br. 15). This is a misunderstanding of Dr. Shugan's conjoint analysis. As illustrated by Exhibits 3—4 in Dr. Shugan's report, the market-share estimate is based on changes in Android preference shares after varying a particular product feature, holding all other features constant among different Android models.

This order, however, need not decide the broad question of whether conjoint analyses are rigorous enough for predicting changes in market share. As the following section explains, Dr. Shugan's conjoint analysis in this particular instance is an unreliable predictor of market share.

B. Unreliable Market Share Calculation.

Google argues that Dr. Shugan's conjoint survey results are unreliable because the features selected to be surveyed, only seven in total, were purposely few in number and omitted important features that would have played an important role in real-world consumers' preferences. Google argues that this inappropriately focused consumers on artificially-selected features and did not reliably determine real-world behavior. This order agrees — on this record for this application.

Dr. Shugan's own focus-group research discovered 39 features that real-world consumers said they would have considered when purchasing a smartphone, including battery life and cellular network (Shugan Rpt Exh. 1). But instead of testing 39 features in his conjoint analysis, Dr. Shugan selected seven features to be studied, three of which were covered by the patented functionality. It is highly likely that study participants would have placed greater importance on a feature like startup time if it were shown with six other features as opposed to 38 other features. In the first scenario, participants in the study were artificially forced to focus on startup time even if in the real world, startup time was unimportant to them. If Dr. Shugan had instead showed 39

14

different features to a study participant, then startup time (i.e., the patented functionality) may have been drowned out by the multitude of other features that are considered by real-world consumers. In the real world, a consumer is faced with many features when making a decision to purchase, not artifically focused on a particular feature. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that important product features, such as battery life, WiFi, weight, and cellular network, all of which were not covered by the patented functionalities, were purposely left out and replaced with an arguably unimportant feature, voice dialing. Dr. Shugan had no reasonable criteria for choosing the four non-patented features to test; instead, he picked a low number to force participants to focus on the patented functionalities, warping what would have been their real-world considerations.

In response to this concern, Oracle explains that it is not necessary in a conjoint analysis to test every distinguishing feature that may matter to consumers because study participants are told to hold all other features constant (Shugan Decl. ¶ 25, 38). That may be true in theory. But here, the conjoint study's own irrational results shows that study participants did not hold all other, non-tested features constant. Specifically, the results show that one quarter of all participants preferred (9%), or were statistically indifferent between (16%), a smartphone costing $200 to a theoretically identical smartphone costing $100 (Zimmer Decl. Ex F at 114, Shugan Decl. ¶ 39; Shugan Reply Rep. 19). The likely explanation for this irrational result is that survey respondents were not holding non-specified features constant and instead placing implicit attributes on features such as price.

Oracle responds to this concern by arguing that irrational results, such as this, are acceptable as long as those participants were consistent in their irrationality for each product combination (Shugan Decl. ¶ 33):

When respondents implicitly attribute aspects of other attributes to price or brand name, that is not inconsistent with holding constant all other variables that are not included in the conjoint study. There is no reason to believe that respondents who do enrich the value of the price or brand with variables not included in the conjoint study vary their evaluation of price or brand between the 16 choice sets from which they choose their preferred smartphones. Therefore, even if respondents enrich the value of price or brand, [Dr. Shugan is] still able to isolate the incremental benefit of the features at issue accurately. In other words, the meaning of price and brand may

15

differ slightly for some consumers, but each individual consumer can be expected to have a constant view of the meaning of price and brand. That is all that this survey requires.

This post-hoc explanation is not persuasive. There is no reason to think that study participants believed that a $100 price increase for an iPhone has the same implicit attributes as a $100 price increase for an Android or Blackberry. Moreover, it is likely that Dr. Shugan has created this problem for himself. If the conjoint analysis had been expanded to test more features that were important to smartphone buyers (instead of the four non-patented features selected for litigation purposes), then the study participants may not have placed implicit attributes on the limited number of features tested. The conjoint analysis' determination of market share is STRICKEN.

C. Relative Preference Between Application Startup Time and

Availability of Applications.

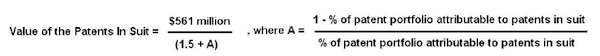

The above-described flaw, however, is not fatal to the conjoint analysis' calculation of the relative preference between "application startup time" and "availability of applications." The study participants were unlikely to infer implicit attributes onto these two features. The calculated relative preference between these two features is sufficiently reliable for the purposes of Daubert. Thus, Dr. Cockburn's use of this relative preference for his apportionment calculation is not stricken. Mathematically, Dr. Cockburn requires this ratio of 2:1 in order to allocate the adjusted starting point of $598 million (now $561 million) between the patents in suit, copyrights in suit, and patents not in suit using an algebraic formula with only one variable to solve. Dr. Cockburn uses the following equation to solve for the value of the patents in suit (Rpt ¶ 414):

And per the conjoint analysis, the value of the copyrights in suit are worth half the value of the patents in suit.

The reader may well reel in disbelief at this equation and wonder how the judge could let it be presented to the jury. While it is sui generis and will not be found in the textbooks, the equation is merely an arithmetical statement of the components previously allowed, such as the assumption that the 2006 value of the copyrights in suit would have been half the 2006 value of

16

the six patents in suit. The jury may well raise a skeptical brow over the seemingly convoluted testimony but that is not the test for Daubert.

4. ECONOMETRIC ANALYSIS.

Throughout the reasonable royalty analysis for each patent and copyright in suit, Dr. Cockburn's report cites his econometric analysis for an estimate of Android's increased market share due to infringement (see Rpt Exhs. 6—11).

For his econometric analysis, Dr. Cockburn sampled 2010 and 2011 eBay auction data for smartphones. This data included, for each auction, the maximum bid, equated to "willingness to pay," and the sales price. Aside from the eBay data, Dr. Cockburn also collected data about the attributes of each auctioned smartphone, such as speed, battery life, and storage space. Using both data sets, Dr. Cockburn conducted a regression analysis to predict "a consumer's willingness to pay" based on a smartphone's features. From this, Dr. Cockburn calculated the decrease in a consumer's willingness to pay for Android phones after removing the patented features (Rpt App. C1-C5).

Using calculated decreases in willingness to pay, Dr. Cockburn extrapolated the predicted decrease to Android's market share after removing the patented features. This was done by looking at the data for bidders who place bids on multiple smartphone models and calculating consumer surplus for each smartphone bid (Rpt App. C12—C13). By comparing each bidder's newly calculated consumer surplus for a slower Android (i.e., Android without the patented features) and unchanged consumer surplus for other smartphones, Dr. Cockburn determined whether that bidder would have purchased the slower Android, purchased another smartphone they had bid on previously, or would not have purchased a smartphone at all.

Dr. Cockburn's determination of market-share impact was unreliable. Specifically, Dr. Cockburn's calculation of Android market share using consumers' willingness to pay was questionable. In his calculation of market-share change, Dr. Cockburn assumed that the sales prices of Android smartphones sold on eBay would remain constant even though he had previously determined that bidders would be less willing to pay for a slower Android.

17

Dr. Cockburn calculated market share by comparing the adjusted maximum bid (willingness to pay for a slower Android) to the unadjusted price at which the Android smartphone actually sold on eBay (sales price of the normal Android). The flaw in the analysis was that the sales price should also have been adjusted because the sales price in Dr. Cockburn's counterfactual was determined by the second highest bidder, whose willingness to pay would have also decreased if Android were slower. Put another way, in the counterfactual with a slower Android smartphone, if the winning bid was decreased because of a drop in consumers' willingness to pay, then every bid should have been decreased, leading to a decrease in the sales price of a slower Android smartphone. By not adjusting sales prices for Android, Dr. Cockburn likely overestimated the decrease in Android market share and thus, overestimated the revenue impact to Google of an Android smartphone without the patented features.

Oracle responds by explaining that for most Android smartphones, Google had no influence over the price at which OEMs sold phones or the extent to which carriers subsidized them (Cockburn Decl. ¶¶ 13—16). This explanation is not persuasive. It is unclear how prices set by OEMs and carriers for new Android phones would impact the sales price for eBay-auctioned Android phones. Dr. Cockburn does not contend in his report that OEMs and wireless carriers set minimum-bid prices for all or most of the eBay Android smartphones sold. The sales prices for eBay-auctioned Android smartphones were set by the winning bid. Indeed, Oracle's explanation highlights the disconnect between Dr. Cockburn's methodology and real-world predictions.

Thus, Dr. Cockburn's econometric calculation of the change in Android market share is STRICKEN.

5. POTENTIAL ISSUES NOT ADDRESSED BY THE PARTIES.

At the hearing, the undersigned judge raised the question of whether Dr. Cockburn's report provides a way for the jury to calculate damages in the event that Oracle prevails on fewer than all patents in suit. Now the only two remaining patents in suit are the '520 and the '104 patents. The Court understands how Dr. Cockburn's group-and-value methodology could arrive at a value for the '104 patent. But in light of the rulings in this order, it seems to the Court that there is no remaining methodology to place a value on the '520 patent. While this was briefly

18

discussed at the hearing, the parties shall also address how this affects, if at all, the copyright allocation, and how the one-half formula will be presented to the jury if Oracle only asserts one- third of the original denominator, the three patents in suit. By NOON ON MARCH 19, each side shall submit ten-page statements on this issue.

The undersigned judge also raised the question of whether the 2006 negotiations, on which Dr. Cockburn's hypothetical negotiation inquiry is based, entailed a fully paid-up license or only a three-year term license for the intellectual property at issue. Dr. Cockburn does not opine on this issue in his report. At the hearing, the parties disagreed with each other on the answer to this question. The Court itself believes this will be important for determining injunctive relief and ongoing royalties. However, since neither party has raised the issue, it will not delay trial, and both sides must take their chances on this one at trial.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the independent-significance approach is STRICKEN. The econometric analysis is STRICKEN. The conjoint analysis' determination of market share is STRICKEN in both Dr. Shugan's and Dr. Cockburn's reports. However, the conjoint analysis' determination of relative importance between application startup time and availability of applications is not stricken. The "upper bound" calculation in the group-and-value approach is STRICKEN. The "lower bound" calculation in the group-and-value approach shall be adjusted by deducting $37 million for the value of the unasserted copyrights from the adjusted starting point of $598 million. Therefore, $561 million shall be the total value of the copyrights in suit and 569 patents in Sun's Java mobile patent portfolio. Both parties shall please advise the Court how Dr. Cockburn's report could calculate a reasonable royalty for each individual patent in light of the items stricken by this order. The parties shall submit ten-page statements on this by NOON ON MARCH 19.

19

In allowing most of the study to be presented to the jury, the Court merely holds that those passages pass a minimum threshold without necessarily suggesting that the methods used are persuasive or the best method to address the problem. No expert witness shall say in the jury's presence that the Court has (or has not) approved any approach.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Dated: March 13, 2012.

/s/ William Alsup

WILLIAM ALSUP

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

20

1 His report was based on the six patents in suit. While the briefing was underway, one was withdrawn with prejudice. After the hearing, another three rejected by the examiner were withdrawn if the trial is held before the administrative appeals are completed, a withdrawal whose effect will be considered below.

786

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.,

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.,

Defendant.

No. C 10-03561 WHA ORDER SETTING TRIAL

DATE OF APRIL 16, 2012

In reliance on Oracle’s withdrawal with prejudice of the ’720, ’205, and ’702 patents,

given the final rejections by the PTO examiner, and having twice admonished counsel to reserve

mid-April to mid-June 2012 for the trial of this case, this order now sets April 16 as the first day

of trial, which will be devoted to jury selection and opening statements. The trial shall continue

day to day on the trifurcated plan previously set and on the daily 7:30 a.m. to one p.m. schedule

previously set, with the trial expected to run about eight weeks. A hardship questionnaire will be

sent by Thursday to the venire to preclear potential jurors for such a lengthy trial. The final

pretrial order was issued earlier on January 4, 2012 (Dkt. No. 675).

Google is hereby encouraged to withdraw its invalidity defenses that have failed in the

reexamination process as a way to further streamline the trial on the two patents remaining in suit.

Dated: March 13, 2012.

/s/William Alsup

WILLIAM ALSUP

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

|

|

|

|

| Authored by: Crocodile_Dundee on Tuesday, March 13 2012 @ 11:51 PM EDT |

...in India.

But I'm glad the judge has decided to push this along.

---

---

That's not a law suit. *THIS* is a law suit![ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: songmaster on Tuesday, March 13 2012 @ 11:59 PM EDT |

| Please list the correction in the title if possible [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 12:06 AM EDT |

For one patent, and the mythical copyright

on that class of expression known as APIs?[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 12:37 AM EDT |

Google is hereby encouraged to withdraw its

invalidity defenses

that have failed in the reexamination

process as a way to further streamline

the trial on the two

patents remaining in suit.

Google wanted

the trial for the fall. So why should it

"streamline" the trial if streamlining

will hasten the trial

to it's (Google's) potential peril? If I were Google, I

would

simply relax by exercising my right to keep my invalidity

defenses.

That way, I might [just] have a chance at a

trial

nearer to my wanted

time-frame, right? [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:04 AM EDT |

$561 million shall be the total value of the copyrights in

suit and 569 patents in Sun's Java mobile patent portfolio.

[...]

each of the

22 top patents has a reasonable royalty of

approximately $20 million

[...]

the equation is merely an arithmetical statement of the

components

previously allowed, such as the assumption that

the 2006 value of the

copyrights in suit would have been

half the 2006 value of the six patents in

suit. [...]

So, if my math is correct, this makes:

- 6

patents-in-suit at "minimum" value of $20M = $120M

(ok, less the one

"unvalued" patent, but let's be generous)

- Value of copyrights is half of

that, or $60M

- Only one patent-in-suit is valued, the other one "up in

the air" right now, so that makes the total damage

- $20M + $60M

+ $X, so in any case most likely less

than $80M (if we are being very

generous)

- Or am I missing a patent here that still remains?

That

seems to be a far cry from the $6B figure initially

floated around... and

probably also not that much more than

the lawyer (and "expert") bills

accumulated so far.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: SilverWave on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:20 AM EDT |

Never

This is Oracle.

:-)

---

RMS: The 4 Freedoms

0 run the program for any purpose

1 study the source code and change it

2 make copies and distribute them

3 publish modified versions

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: ChrisP on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:26 AM EDT |

It's refreshing to find a judge who knows something about statistical analysis

and can see through the 'lies' in the good doctor's reports.

---

SCO^WM$^WIBM^W, oh bother, no-one paid me to say this.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: sproggit on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:45 AM EDT |

This article returns to an unresolved question between the two parties - namely

the duration that would have been agreed had Google and Sun been able to agree

terms for the licensing of patents in their earlier discussions.

On that topic, a couple of obvious questions:-

1. Can anyone think of a reason why Oracle would argue for an irrevocable

license, or why Google would want only a 3-year deal?

2. In the event that a 3-year deal seems likely, are the sums of money

contemplated by the parties reflective of those terms? Oracle were asking for

billions of dollars. That hardly seems realistic for a 3-year license, or did I

miss something?

3. Contemplating an outcome in which a 3-year deal is deemed to be correct, and

a trial outcome in which Google ends up having to pay Oracle an amount in the

tens or hundreds of millions, then would this present a problem for Google?

Could they, in 3 years, re-write the relevant portions of Android such that the

patents were not infringed? [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: SilverWave on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:47 AM EDT |

.

---

RMS: The 4 Freedoms

0 run the program for any purpose

1 study the source code and change it

2 make copies and distribute them

3 publish modified versions

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: feldegast on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:56 AM EDT |

Please make links clickable

---

IANAL

My posts are ©2004-2012 and released under the Creative Commons License

Attribution-Noncommercial 2.0

P.J. has permission for commercial use.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: feldegast on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:57 AM EDT |

Please make links clickable

---

IANAL

My posts are ©2004-2012 and released under the Creative Commons License

Attribution-Noncommercial 2.0

P.J. has permission for commercial use.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: feldegast on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:58 AM EDT |

Thank you for your support

---

IANAL

My posts are ©2004-2012 and released under the Creative Commons License

Attribution-Noncommercial 2.0

P.J. has permission for commercial use.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: janolder on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 05:11 AM EDT |

I'm confused by two things.

First of all, why is the judge pushing for the trial to get underway in April

when he'd just have to wait a few more months for the PTO to toss out the

remaining patents? It seems patently (pun intended) unfair to Google to go to

trial with patents that are likely invalid. Worst case, the jury finds in favor

of Oracle and Google gets to pay tens of millions for patents that get declared

invalid a few months later. If this succeeds, it means that anyone with untested

and likely invalid patents can go ahead and sue with a high likelihood of

squeezing cash out of some enterprise with deep pockets before the PTO makes up

its mind to invalidate it.

Secondly, isn't the question whether APIs are copyrightable a matter of law?

Seems to me this fundamental question could and should be addressed prior the

scheduling the trial. If it is found that APIs can't be copyrighted the trial

could be shortened considerably especially if all the remaining patents are

found to be invalid. No weeks of trial is better than eight weeks for a busy

judge.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: DaveJakeman on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 06:51 AM EDT |

Early on, the judge was talking about a three-week upper time limit for the

trial. Now, having pared much of what needs to be tried down to the bone, we're

up to eight weeks of trial. For what? Why?

This does not make sense.

---

When a well-packaged web of lies has been sold gradually to the masses over

generations, the truth seems utterly preposterous and its speaker a raving

lunatic.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: bugstomper on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 08:12 AM EDT |

As Judge Alsop said, could you check my math here? I think he got it wrong but

maybe I'm just up too late :D

Regarding that equation: He says that it was necessary for Dr. Cockburn to have

numbers for users' relative preference for "application startup time"

and "availability of applications" so that he could assign a ratio of

2:1 for the value of patents vs copyright. I interpret that this way:

The total number of the value based on all the intellectual property that Google

was negotiating for from Sun comes to $561 million, comprised of patents and

copyrights. Dr. Cockburn is saying that the main value to the user of the

patents is speeding up application startup. The main value to the users of

Google having use of the API copyrights is in increased availability of

applications, presumably because being able to have Android apps written in Java

results in more apps being available.

Cockburn's "logic" says that if market preference studies show that

fast application startup is twice as important a feature to users than wide

availability of apps, then somehow it makes the dollar value of the patent

portion of the portfolio worth twice as much for Google to purchase than the

copyrights to the APIs. Ignoring of course, that the speedup in application load

time attributable to the technology of the patent might not be so much that any

users would actually notice enough to change their buying habits, and that the

number of apps available if another language were to be used instead of Java

might not change if Google decided to spend the money on attracting more

Objective C or C++ or Python developers instead paying Sun for use of the Java

API.

Anyway. that makes the value of the patent portion of the portfolio equal to 2/3

of $561M and the value of the copyright portion 1/3 of $561M.

Now lets say that the value of the patents in suit is some fraction of the value

of all the patents, just to pick a number out of the air, 5/7. Then the value of

the patents not in the suit is 2/7 of the total value of the patents, which can

also be written as 1 - 5/7

If I were to calculate the value of the patents in suit, I would say $561M times

the proportion that is patents, which is 2/3, times the proportion of the

patents that are in suit, which in my pulled out of the air example is 5/7. To

make it look a little more like Dr' Cockburn's I could say that multiplying by

2/3 is the same as dividing by 1.5, so that would be $561M times 5/7 the whole

thing divided by 1.5.

Or to use a variable x for the proportion of the value of the patents

attributable to the patents in suit that would be ($561M * x)/1.5 where x is

somewhere between 0, for the patents in suit are worthless, to 1, for the

patents not in the suit are worthless.

But Judge Alsop quotes Dr. Cockburn as using a different equation. First of all

he says "% of patent portfolio..." instead of "fraction of patent

portfolio..." which is just plain sloppy. But assuming he means what I call

x, then his formula can be expressed as $561M/(1.5 + (1-x)/x)

Here is a graph comparing those two equations. I apologize for giving you a

shortened URL made at goo.gl. You'll have to trust me that it goes to a graph at

fooplot.com which is a site where you can graph equations and make a URL out of

the equation you are plotting. I don't think the geeklog software would handle

the non-shortened URL. Out of politeness I will not make the link clickable.

Copy and paste it in your browser if you want to see the graph. Javascript will

be required.

http://goo.gl/m5kdw

The red plot is what I think is correct. The black plot is Dr. Cockburn's

formula. Notice that both of them show the same value at the ends, i.e., they

correctly show that the patents in suit are worth 0 if they are worthless and

worth 2/3 of 561 if they hold all of the worth of the patents.

But in between those limits, Dr. Cockburn's equation adds up to about $40m to

the value over the simpler, and I think correct, formula.

That seems sneaky.

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 09:37 AM EDT |

Normally Groklaw pages fit the width of my browser, but now, not even full

screen will remove the need to have to scroll left and right to read the story.

Very annoying.

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: caecer on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 10:01 AM EDT |

Doesn't the fact that not all of Cockburn's report was stricken mean that the

independent expert also now gets to submit his report? That might be

interesting. Or am I mistaken on this one?[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:15 PM EDT |

So the 8 weeks finish immediately before Van Nest's second conflicting trial

(though there's the pretrial conference for that), but start before his first

conflicting trial ends. Was that in fact rescheduled? If he notified the court

as he indicated he would, I didn't see a filing for it.

(Conflict

details would be here

except that that page has an href="748" where it should have name="748" :)

.) [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Imaginos1892 on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 02:26 PM EDT |

Yup, "no value" sounds about right. Can we all go home now?

-----------------

Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!![ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: maroberts on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 03:19 PM EDT |

What is it with the 500 odd million mentioned in here? I thought we were down to

under 100 million as a likely end result?[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 05:30 PM EDT |

Maybe I'm dense, but I'm trying to figure out whether or not some of patent

claims were dismissed with prejudice or whether they're half-life zombies.

I thought the judge gave an either/or choice to Oracle. If you want an early

trial, drop patents with prejudice. Oracle proposed Zombie Patents. (They

would drop them unless they were found, later, to be valid.)

From what I can tell, the judge caved on this. Am I wrong or do we have Patent

Zombies possibly lurking in the future?

Can Google win this case, only to have some miracle Zombie resurrection of a

patent, which starts the case all over again? [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: sproggit on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 07:03 PM EDT |

From the top of page 5 of the Order:

"Moreover, as Dr.

Cockburn himself writes elsewhere in his report, patents in a single portfolio

derive value from complementing each other to prevent design around, meaning

that unasserted patents are valuable because they prevent design around asserted

patents (Rpt ¶ 335)."

So here we have a respected

member of the judiciary - one who has considerable experience of dealing with

patent disputes, writing that not only is it acceptable for a company to patent

software, but it's acceptable for them to patent as many alternative mechanisms

of achieving the same end result, to prevent design around.

Come

on! At what point does this become racketeering? This is extortion, plain and

simple.

What is it going to take for lawmakers to wake up and realise

that the best way for countries in the West to dig themselves out of the current

deficit/financial crisis is to innovate, or that the present patent laws (and

applications thereof) are making it almost impossible for innovation to take

place?

And before you challenge and claim that, well, the little guys

might be blocked, but the big guys can still innovate because they have patent

arsenals... just look around you.

The big players are spending more

energy and effort suing eachother than they are on innovating.

If we

all woke up tomorrow to discover that astronomers had just discovered a

50-mile-wide asteriod heading for a collision with the planet and the only way

of stopping it was to build and launch a complex space mission, there would just

be some smart-alec patent troll out there who would threaten to sue the rescue

team into the stone age for infringing on their "method and concept" for saving

the human race.

And if that happens? Please, don't pay. The sooner we

let Darwin sort this mess out, the better. [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 07:37 PM EDT |

Let f be the fractional value of the patents in suit, which is a number between

0 and 1.

Then the formula given for the value is $561 million / ( 1/2 + 1/f ) = $1.122

billion times f / (2 + f)

This is approximately $374 million times f +/- $38 million.

Or approximately $374 million times f + $153 million times (f-f^2) +/- $3.2

million.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 07:41 PM EDT |

Do jurors get paid?

I've only done jury service on criminal trials. In each case the compensation

for my time was pathetic but I did not begrudge that as I regarded it as my

civic duty.

However in this case jurors are being asked to give up 8 weeks of their time to

listen to one megawealthy corporation trying to batter another into submission

with silly market distorting patents. I think I would be extremely unhappy if

asked to serve on such a jury. [ Reply to This | # ]

|

- 8 weeks! - Authored by: rcsteiner on Thursday, March 15 2012 @ 02:28 AM EDT

- 8 weeks! - Authored by: Anonymous on Thursday, March 15 2012 @ 04:04 AM EDT

- 8 weeks! - Authored by: Anonymous on Thursday, March 15 2012 @ 07:01 AM EDT

- 8 weeks! - Authored by: greed on Thursday, March 15 2012 @ 03:55 PM EDT

- Pay - Authored by: Anonymous on Thursday, March 15 2012 @ 11:02 AM EDT

- Pay - Authored by: Anonymous on Saturday, March 17 2012 @ 08:32 AM EDT

| |

| Authored by: JonCB on Wednesday, March 14 2012 @ 11:50 PM EDT |

Assuming someone is paying attention enough to be able to

quickly put it together(because I know i'm not :D), It might

be interesting to summarise what we know so far. I.e. These

are Oracle's remaining accusations, these are google's

remaining defense's for each etc...

Might make things easier to follow later.

P.S. Mark, if you were planning to do this later then

apologies for upstaging you :). I only make this comment

because i found myself thinking, "So what of google's

defenses have been rejected by USPTO?".[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Thursday, March 15 2012 @ 02:38 AM EDT |

This line is interesting:

If each patent covers only one invention, then each claim represents merely

different shades of the same invention and it is reasonable to require — in the

hypothetical negotiation — that the infringer license the entire patent. Thus,

Dr. Cockburn is not required to apportion damages on a claim-by-claim basis

Could it be that the judge plans to hold Oracle to the idea that each patent is

one invention and that the claims are clarifiers of that one invention? That

limitation might come back to bite them in the behind later, I wonder if that's

why be retreated on it.

cheers

Frank[ Reply to This | # ]

|

|

|

|

|