|

|

| Oracle v. Google - The Pretrial Issues |

|

|

Monday, November 21 2011 @ 09:30 AM EST

|

Now that almost all of the motions have been disposed of (the remaining motion open being Oracle's motion to exclude portions of the damage reports from Drs. Leonard and Cox on behalf of Google), the focus turns to how to conduct the trial, and once again we see the sides at odds. This is not really surprising. How issues are dealt with at trial and the instructions given to the jury will be huge factors in the outcome of this dispute, especially on the copyright side of the ledger.

Back on October 26 Judge Alsup issued a proposed trial plan (564 [PDF; Text]) in which he proposed a three phase (or trifurcated) trial:

Phase One. Liability on the copyright claims, including all defenses thereto, will be tried and determined by special verdict before going to Phase Two.

Phase Two. Liability on the patent claims, including all defenses for the jury. The jury will decide these issues before going to Phase Three.

Phase Three. All remaining issues will be tried, including damages and willfulness.

Judge Alsup saw this as a reasonable approach where the most general evidence would be presented in the first phase, which could then be rolled forward and relied upon in the subsequent phases of the trial. This approach would allow the jury to focus on one major issue at a time until the final willfulness/damages phase. It could also potentially shorten the entire trial in the event that the jury decided there was no copyright or patent infringement, i.e., it would eliminate the need for the final phase.

Google agrees with this (628 [PDF; Text]), but Google also takes the opportunity in its response to suggest a stay in the proceedings pending the outcome of the the reexamination of the asserted Oracle patents by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office:

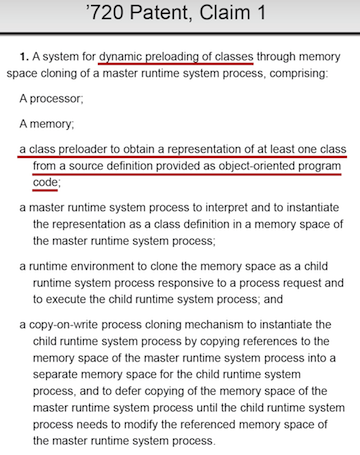

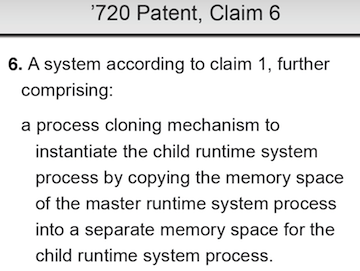

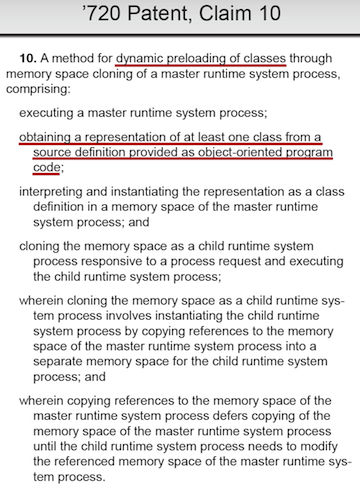

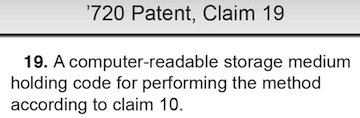

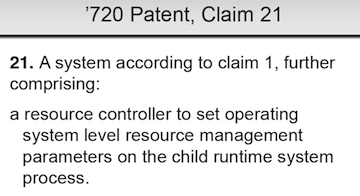

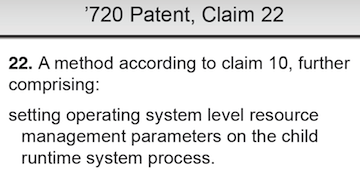

Those proceedings are actively affecting the scope of this litigation. For example, the PTO recently closed prosecution proceedings for the ’720 patent with rejections on all of the asserted claims of that patent, which represent almost a quarter of the patent claims asserted in this case. And throughout the reexamination proceedings, Oracle has been forced to change the scope of its patent claims, making unambiguous arguments for a narrow construction of certain claim terms as well as amending and adding new claims. The patent case should be stayed to allow the reexamination proceedings to run their course so that this Court’s proceedings are not merely duplicative of PTO activity or, worse, unnecessary.

More on the '720 patent reexam later, but suffice it to say, the USPTO has torpedoed that patent with the only surviving claims being two dependent claims, neither of which Oracle asserted in this action. Unless Oracle manages to resurrect this reexamination (Oracle does have 30 days to respond to the USPTO), this will take 6 of the 26 asserted claims off the table.

Beyond the '720 patent, Google makes a compelling case for a stay, pointing out that, in addition to the likely loss of the '720 claims, Oracle has already narrowed other asserted claims and is statistically likely to be forced to alter most, if not all, of the asserted claims during the reexaminations. Moreover, any complaint Oracle makes about delay caused by the reexaminations is, Google suggests, of Oracle's own doing because Oracle is prolonging the reexaminations with some of its actions:

Oracle has requested several extensions of time—USPTO Reexam Control Nos. 95/001,560 (Apr. 29, 2011), 90/011,521 (July 15, 2011), and 90/011,492 (July 5, 2011)—and has filed each response on the final day possible. Moreover, in one reexamination proceeding, Oracle actually added claims, which could delay further the issuance of a final office action. (USPTO Reexam Control No. 95/001,548, Amendment (Oct. 19, 2011)). Oracle’s tactics in the reexamination proceedings belie any argument that a stay of the patent case pending completion of those proceedings would somehow prejudice Oracle by delaying its right to relief.

Google suggests at least one additional action to facilitate the trial, and that is the videotaping of early witnesses whose testimony will be relied upon again later in the trial. Why do this? Because of the complexity of the case. Per Google:

This case plainly is complex. Concepts like “application programming interfaces” and “virtual machines” will be foreign to most jurors. The sheer breadth of the case adds to the complexity. Oracle’s patent case alone involves 26 claims of six unrelated patents. Oracle proposes 59 jury instructions. Its verdict form includes 110 questions of fact for the jury. The joint exhibit list is 161 pages long and lists thousands of potential exhibits. It is unreasonable to expect a jury to digest all of this information over the course of a single, colossal, multi-week trial.

How would you like to be called for jury duty on this one?

Of course, Oracle does not see the approach to the trial in the same light as either Judge Alsup or Google, stating "trifurcating the trial would raise problems of efficiency, duplication, and jury understanding." (627 [PDF; Text]) Oracle complains:

The Court’s comment that “evidence presented in an earlier phase can be used by counsel and by the jury in a subsequent phase” may contemplate invoking earlier evidence without recalling witnesses. But, as a practical matter, it is not clear how the relevant evidence could be introduced in an earlier phase and then effectively re-used in a later phase without recalling the witnesses needed to present it or permitting counsel to summarize the previous evidence relevant to a subsequent phase.

This is exactly why Google suggests videotaping witnesses in the earlier phases.

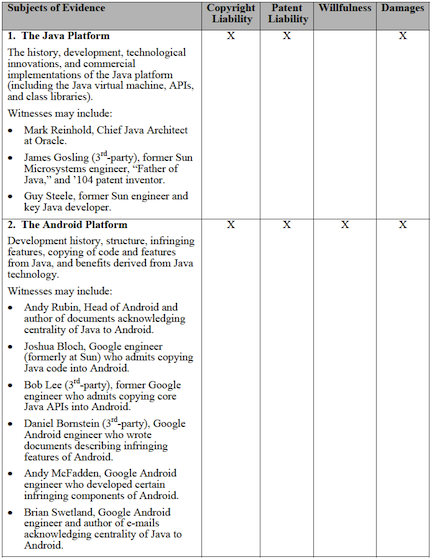

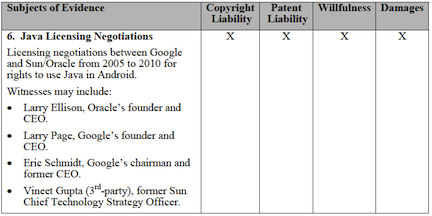

Oracle argues that the issues of copyright infringement liability, patent infringement liability, willfulness and damages are inseparable, but what they are really arguing is that the same witnesses will be relied upon in combinations of these issues. That does not mean that the testimony those witnesses provide on one issue will be relevant to the other issues. Oracle provides a table showing witnesses that MAY be called to address some combination of these issues, but one can reasonably conclude that, in some or most of the cases, testimony that is offered on copyright infringement does not likely address patent infringement. Oracle even admits this:

Dr. Reinhold, for instance, and other Sun/Oracle engineers and executives possess information on both copyright and patent-related subjects and are expected to testify as to both.

Finally, Oracle argues that they will be prejudiced by a three-phase trial:

Separating the presentation of evidence into multiple phases would prejudice Oracle and greatly inconvenience the witnesses, the jury and the Court. If the parties are not permitted to recall witnesses in subsequent phases, juror memory attrition would become an issue, particularly if the deliberations between the phases go long. See A.L. Hansen Mfg. Co. v. Bauer Prods., Inc., No. 03 C 3642, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 8935, at *16 (N.D. Ill. May 17, 2004) (“[T]he more time taken between trial phases, the greater the risk of losing jurors or having their memory fade before evaluating the totality of the circumstances”). In such a case, Oracle would be forced to select and repeat the key evidence in subsequent phases in order to ensure that the jury continues to consider the relevant evidence. The memory attrition issue becomes particularly acute given that this is a technical case where the jury is unlikely to fully comprehend or appreciate the significance of the patent evidence if Oracle is required to introduce it during the copyright phase of trial.

What Oracle doesn't explain is how, if these circumstances occur, Oracle is prejudiced to any greater extent than Google. In the end Oracle is asking for a single trial with all evidence presented at once and with only the jury deliberations separated into three phases. It is hard to see how this approach would improve the jury's ability to cope with all of the information because the jury would likely be unable to keep track of what evidence is related to copyright infringement versus patent infringement. I suspect this is exactly what Oracle is hoping for, i.e., that the jury will be confused and will ultimately conclude (I can already hear all of the pejorative terms being thrown around at trial by Oracle the way they have done in their motions) that Google has to have infringed something. THAT would be prejudicial to Google.

I will venture that the court sticks with its original trifurcated trial plan.

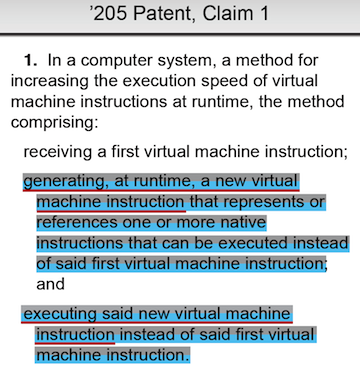

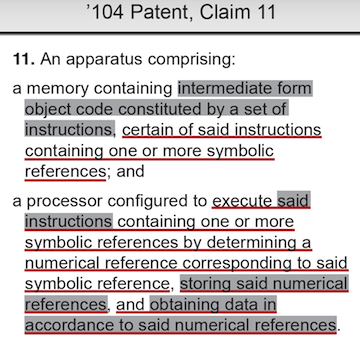

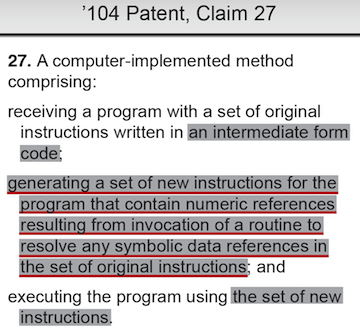

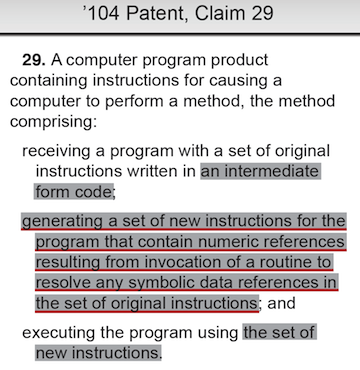

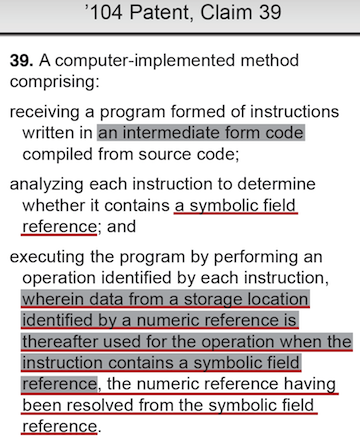

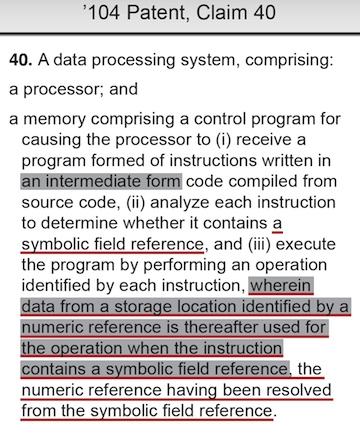

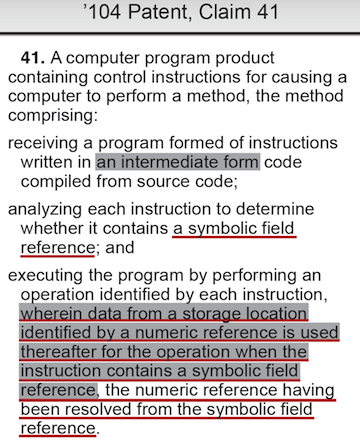

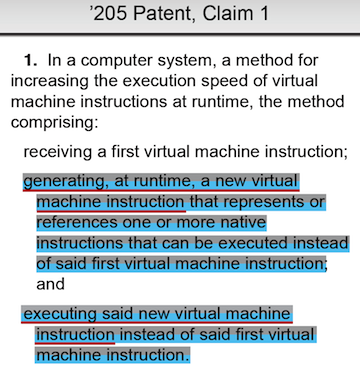

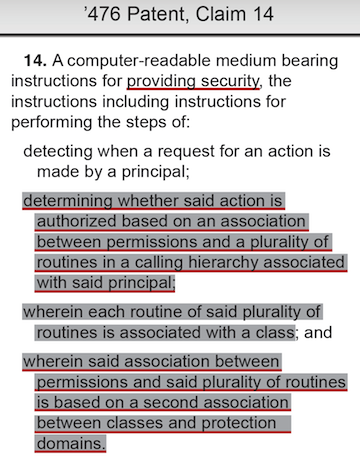

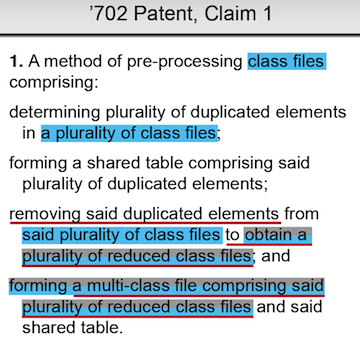

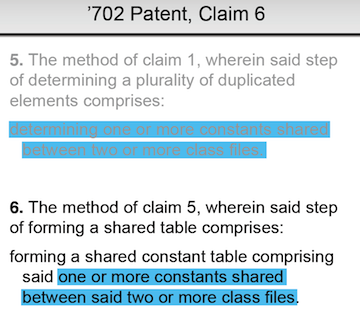

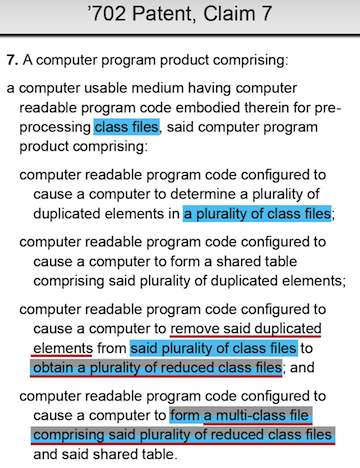

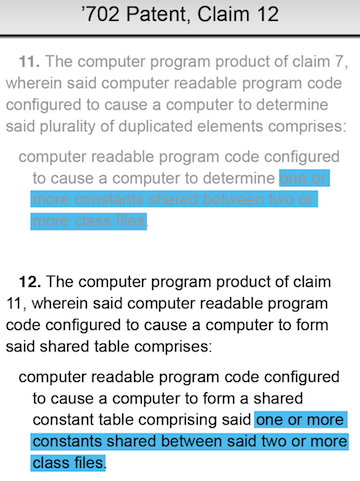

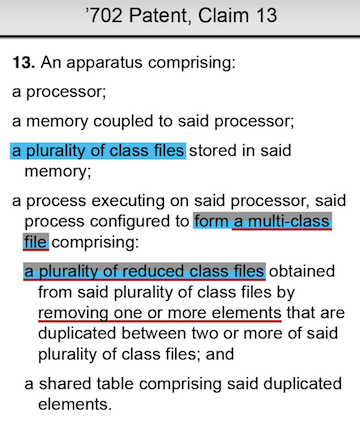

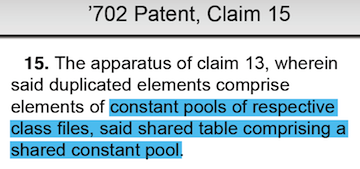

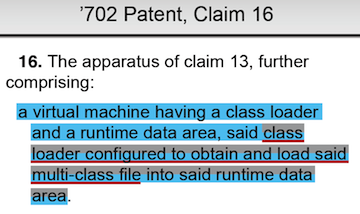

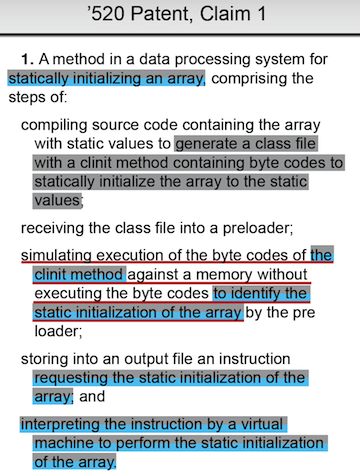

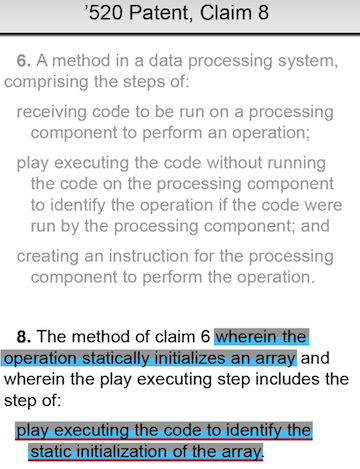

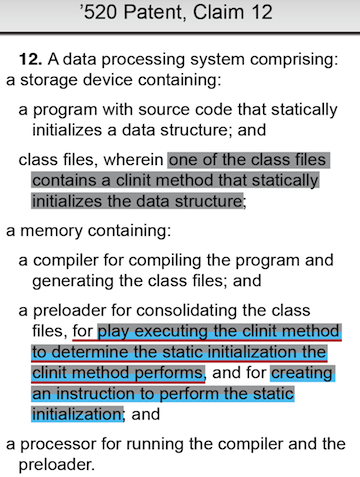

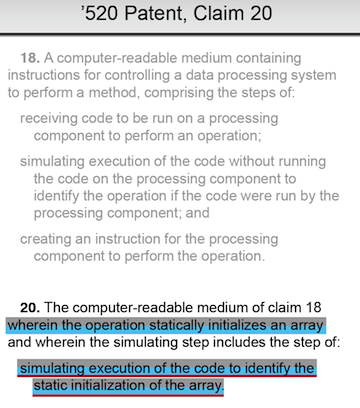

The court also suggested that the parties prepare visual aids in the form of color coded claim charts to assist the jurors in focusing on the claim elements that must be proven but which Google, as defendant, asserts it does not practice. (587 [PDF; Text]) The court's instructions for the preparation of these slides:

Each claim is on a separate page and the few phrases usually alleged to be missing from the accused item (for infringement purposes) and from the prior art reference (for anticipation purposes) are highlighted in colors coded to the respective issues. We will try this in the instant action. ... [D]efendant shall identify to plaintiff in writing its best two references for anticipation purposes as to each of the 26 claims to be tried identified by plaintiff ... [P]laintiff shall highlight in gray each phrase it contends is missing from Reference No. 1 for anticipation purposes and shall highlight in blue each phrase it contends is missing from Reference No. 2 for anticipation purposes. Non-highlighted phrases will be deemed conceded as to those references. ... [D]efendant shall highlight in pink each phrase it contends is missing from the accused device or method. The remainder will be deemed conceded. ... Counsel shall use their best judgment as to the most effective way to visually communicate both the infringement and anticipation issues using only one copy of each claim to be tried. For example, in a previous trial, counsel clarified overlap by using red underlining (instead of pink highlighting) to identify phrases disputed as to infringement, while using parallel bands of highlighting to identify phrases disputed as to the two anticipation references.

The result, as submitted by Google on behalf of the parties (626 [PDF; Text]), may be found in the slides found in document 625 [PDF; Images])

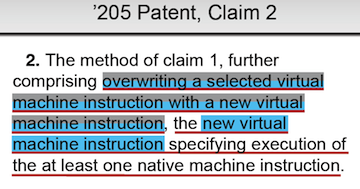

To see how this works, look at the slide for Claim 1 of the '205 patent.

This slide shows text highlighted in gray (phrases Oracle contends are missing from Reference No. 1 for anticipation purposes), blue (phrases Oracle contends are missing from Reference No. 2 for anticipation purposes), and underlined in red (each phrase Google contends is missing from the software that Oracle has accused of infringement, specifically the Android Software Development Kit version 2.2 (the "SDK")).

In submitting the slides Google points out that they have their limitations. Because of "Oracle's non-specific allegations and generalized contentions related to both direct and indirect infringement," Google states that it has limited the slides to issues of direct infringement. Moreover, the slides do not reflect claims that Oracle is likely to lose (remember the problem with the '720 patent in reexam).

Most importantly, Google places on the record its objection to the use of the slides as a point of proof, i.e., the burden of proof as to infringement remains with Oracle with respect to the claims in their entirety, not just the highlighted portions. This objection is in response to the court's statement in the original proposal that "[n]on-highlighted phrases will be deemed conceded as to those references."

The final action from last Friday was the court's order furthering the stipulation as to the remaining three depositions. 624 [PDF; Text])

**************

Docket

624 – Filed and Effective: 11/18/2011

ORDER

Document Text: ORDER GRANTING STIPULATED REQUEST TO EXTEND TIME FOR BRAY AND RIZZO DEPOSITIONS re 623 Stipulation filed by Google Inc.. Signed by Judge Alsup on November 18, 2011. (whalc1, COURT STAFF) (Filed on 11/18/2011) (Entered: 11/18/2011)

625 – Filed and Effective: 11/18/2011

Statement

Document Text: Statement re 587 Order Joint Proposed Color-Coded Handout by Google Inc. (Van Nest, Robert) (Filed on 11/18/2011) (Entered: 11/18/2011)

626 – Filed and Effective: 11/18/2011

Letter

Document Text: Letter from Robert A. Van Nest re: Color-Coded Handout. (Van Nest, Robert) (Filed on 11/18/2011) (Entered: 11/18/2011)

627 – Filed and Effective: 11/18/2011

RESPONSE

Document Text: RESPONSE to re 564 Order Oracle America Inc.'s Critique of the Court's Proposed Trial Plan by Oracle America, Inc. (Jacobs, Michael) (Filed on 11/18/2011) (Entered: 11/18/2011)

628 – Filed and Effective: 11/18/2011

RESPONSE

Document Text: RESPONSE to re 564 Order re: Proposed Trial Plan by Google Inc. (Van Nest, Robert) (Filed on 11/18/2011) (Entered: 11/18/2011)

***************

Documents

624

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.

Defendant.

CASE NO. CV 10-03561 WA (DMR)

STIPULATION AND

ORDER TO EXTEND TIME FOR

DEPOSITIONS OF TIMOTHY

BRAY AND JOHN RIZZO

Dept.: Courtroom 8, 19th Floor

Judge: Honorable William Alsup

STIPULATION

WHEREAS, the Court’s order of November 14, 2011 (Dkt. No. 617) required that Oracle

designate three interviewees for deposition, and that those three depositions be completed by

November 22, 2011; and

WHEREAS, on November 15, 2011, Oracle informed Google that it wanted to take the

depositions of Timothy Bray, John Rizzo, and Dan Bornstein; and

WHEREAS, on November 16, 2011, Google offered Mr. Bornstein for deposition on

Monday, November 21, 2011; and

WHEREAS, on November 17, 2011, Oracle accepted that offer and agreed take Mr.

Bornstein’s deposition on November 21, 2011; and

WHEREAS, prior to the Court’s November 14, 2011 order, the parties had scheduled the

interviews of Google employee Timothy Bray and third party John Rizzo for November 30, 2011;

and

WHEREAS, Mr. Bray is currently traveling in Asia and will not be returning to the United

States until after the Court’s deadline of November 22, 2011; and

WHEREAS, because Mr. Rizzo is not a Google employee, his day-to-day availability for

proceedings in this case is not subject to Google’s control, but Mr. Rizzo had voluntarily agreed

to accept service of a deposition subpoena and sit for deposition on November 30, 2011, and

Oracle had issued a deposition subpoena to Mr. Rizzo for that date; and

WHEREAS, accordingly, on November 16, 2011, Google proposed to Oracle that, subject

to Court approval, the depositions of Mr. Bray and Mr. Rizzo should take place on the previously

agreed date of November 30, 2011; and

WHEREAS, on November 17, 2011, Oracle agreed to accommodate Mr. Bray’s and Mr.

Rizzo’s schedules by deposing those witnesses on November 30, 2011; and

WHEREAS, the parties acknowledge and agree that a limited extension of time to depose

Mr. Bray and Mr. Rizzo will not affect, delay, or push back any other deadlines in this case or

cause any prejudice to either Google or Oracle.

1

NOW THEREFORE THE PARTIES HEREBY STIPULATE AND AGREE that:

1. The deadline for completing the depositions of Timothy Bray and John Rizzo

should be extended from November 22, 2011 to November 30, 2011.

2. No other deadlines in this case will be affected by the foregoing extension. The

parties will not use this extension to argue for a delay of any other deadlines in this case.

ORDER

The foregoing stipulation is approved, and IT IS SO ORDERED.

Date: November 18, 2011

/s/ William Alsup

Honorable William Alsup

Judge of the United States District Court

2

Dated: November 17, 2011

BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER LLP

By: /s/ Steven C. Holtzman

DAVID BOIES (Admitted Pro Hac Vice)

[email address telephone fax]

STEVEN C. HOLTZMAN (Bar No. 144177)

[email]

FRED NORTON (Bar No. 224725)

[email address telephone fax]

ALANNA RUTHERFORD (Admitted Pro Hac Vice)

[address telephone fax]

MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP

MICHAEL A. JACOBS (Bar No. 111664)

[email]

MARC DAVID PETERS (Bar No. 211725)

[email]

DANIEL P. MUINO (Bar No. 209624)

[email address telephone fax]

ORACLE CORPORATION

DORIAN DALEY (Bar No. 129049)

[email]

DEBORAH K. MILLER (Bar No. 95527)

[email]

MATTHEW M. SARBORARIA (Bar No. 211600)

[email address telephone fax]

Attorneys for Plaintiff

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

3

Dated: November 17, 2011

KEKER & VAN NEST LLP

By: /s/ Daniel Purcell

KEKER & VAN NEST LLP

ROBERT A. VAN NEST (SBN 84065)

[email]

CHRISTA M. ANDERSON (SBN 184325)

[email]

DANIEL PURCELL (SBN 191424)

[email address telephone fax]

KING & SPALDING LLP

SCOTT T. WEINGAERTNER (Pro Hac Vice)

[email]

ROBERT F. PERRY

[email]

BRUCE W. BABER (Pro Hac Vice)

[email address telephone fax]

KING & SPALDING LLP

DONALD F. ZIMMER, JR. (SBN 112279)

[email]

CHERYL A. SABNIS (SBN 224323)

[email address telephone fax]

GREENBERG TRAURIG, LLP

IAN C. BALLON (SBN 141819)

[email]

HEATHER MEEKER (SBN 172148)

[email address telephone fax]

Attorneys for Defendant

GOOGLE INC.

4

ATTESTATION

I, Daniel Purcell, am the ECF User whose ID and password are being used to file this

STIPULATION AND [PROPOSED] ORDER TO EXTEND TIME FOR DEPOSITIONS OF

TIMOTHY BRAY AND JOHN RIZZO. In compliance with General Order 45, X.B., I hereby

attest that Steven C. Holtzman has concurred in this filing.

Date: November 17, 2011

/s/ Daniel Purcell

DANIEL PURCELL

5

625

626

[KEKER & VAN NEST LLP letterhead]

November 18, 2011

Honorable William Alsup

U.S. District Court

Northern District of California

Courtroom 8 - 19th Floor

450 Golden Gate Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94102

Re: Oracle America, Inc. v. Google Inc., No.: 3:10-cv-03561 WHA

Dear Judge Alsup:

Pursuant to the Court's Order (Dkt. No. 587) Google has conferred with Oracle to develop handouts which have been filed today as Dkt. No. 625. Those handouts contain the text of the presently asserted claims, highlighted to indicate each phrase Google contends is missing from the software that Oracle has accused of infringement, specifically the Android Software Development Kit version 2.2 (the "SDK"). In providing these contentions regarding the elements missing from the SDK, Google does not concede that Oracle is relieved of its burden of proof as to the other elements of the asserted claims. Google objects to any case management order that would alter the burden of proof or relieve any party of its burden of introducing evidence demonstrating the presence of all elements of a claim in a specific accused infringing instrumentality at trial. Oracle has generally accused a number of devices, computer-readible media, and activities of infringing twenty-six claims across six unrelated patents. Further, Oracle has alleged direct and indirect infringement in various contexts. Google has repeatedly object to Oracle's non-specific allegations and generalized contentions related to both direct and indirect infringement. Google maintains these objections, but reflecting them on the jury handouts would effectively require highlighting the entirety of each claim, rendering the handouts not useful for the purpose for which the Court appears to intend them. Google has refrained from doing so here, and has accordingly highlighted the claims based on Oracle's allegations of direct infringement cause by the use of the SDK.

Google further observes that the handouts submitted for the '720 patent do not reflect any highlighting for Oracle's contentions of elements allegedly missing from the asserted prior art, while the handouts submitted for the '104 patent reflect only the highlighting for Oracle's contentions of elements missing from a single piece of prior art, the Gries reference. Google intends to demonstrate that the '720 patent is invalid over two obviousness combinations

Honorable William Alsup

November 18, 2011

Page 2

(Bryant/Traut and Webb/Kuck/Bach), and that the '104 patent is invalid over the Gries reference and the obviousness combination of Davidson/AT&T. Google so informed Oracle on the schedule set forth in the Order, but Oracle declined to highlight the claim elements that its contends are missing from those combinations of prior art. Oracle contends that the Court's Order, as a result of its use of the term "anticipation," only required it to take a position on the elements missing from single pieces of prior art, not obviousness combinations. Google does not agree with that interpretation of the Court's Order, as the jury will be aided by knowing the elements, if any, Oracle contends not to be present in the prior art obviousness combinations that Google intends to advance at trial. The parties have met and conferred on the subject, but have not been able to reach agreement. Google therefore respectfully seeks the Court's guidance on this issue, and requests that Oracle be required to provide its contentions as to the elements of the asserted claims, if any, missing from the prior art combinations that Google has selected.

Sincerely,

/s/ Robert A. Van Nest

Robert A. Van Nest

627

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.

Defendant.

Case No. CV 10-03561 WHA

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.’S

CRITIQUE OF THE COURT’S

PROPOSED TRIAL PLAN

Dept.: Courtroom 8, 19th Floor

Judge: Honorable William H. Alsup

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. INTRODUCTION ...... 1

II. LEGAL STANDARD ...... 2

III. THE COPYRIGHT, PATENT, WILLFULNESS, AND DAMAGES ISSUES IN

THIS CASE ARE NOT CLEARLY SEPARABLE ...... 2

IV. TRIFURCATION WILL PREJUDICE ORACLE AND INCONVENIENCE THE

WITNESSES AND JURY ...... 11

V. ORACLE’S PROPOSED ALTERNATIVE: A SINGLE TRIAL WITH PHASED

JURY DELIBERATIONS ...... 11

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

CASES

A & M Records, Inc. v. Napster,

239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir. 2001) ...... 6

A.L. Hansen Mfg. Co. v. Bauer Prods., Inc.,

No. 03 C 3642, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 8935 (N.D. Ill. May 17, 2004) ...... 11

Elvis Presley Enters. v. Passport Video,

349 F.3d 622 (9th Cir. 2003) ...... 9

GEM Acquisitionco, LLC v. Sorenson Group Holdings, LLC,

No. C 09-01484 SI, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 50622 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 27, 2010) ...... 2

Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A.,

131 S. Ct. 2060 (2011) ...... 6

Haworth, Inc. v. Herman Miller, Inc.,

No. 1:92 CV 877, 1993 WL 761974 (W.D. Mich. July 20, 1993) ....... 8

In re Seagate Tech., LLC,

497 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (en banc) ...... 7

In re Sortwell, Inc.,

No. C 08-05167 JW, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 121618 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 12, 2011) ...... 9

Kos Pharms., Inc. v. Barr Labs., Inc.,

218 F.R.D. 387 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) ...... 7

Louis Vuitton Malletier, S.A. v. Akanoc Solutions, Inc.,

658 F.3d 936 (9th Cir. 2011) ...... 7

Lutron Elecs. Co., Inc. v. Crestron Elecs., Inc.,

No. 2:09 cv 707 DB, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 49623 (D. Utah May 19, 2010) ...... 9

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd.,

545 U.S. 913 (2005) ...... 6

Newton v. Diamond,

388 F.3d 1189 (9th Cir. 2003) ...... 10

Wang Labs., Inc. v. Mitsubishi Elecs. Am., Inc.,

No. CV 92-4698 JGD, 1994 WL 471414 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 3, 1994), aff’d on other

grounds, 103 F.3d 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1997) ...... 8

WeddingChannel.com, Inc. v. The Knot, Inc.,

No. 03 Civ. 7369 (RWS), 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25749 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 23, 2004) ...... 7, 8

ii

STATUTES

17 U.S.C. § 107 ...... 9

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 42(b) ...... 2

iii

I. INTRODUCTION

Bifurcating or trifurcating the trial would raise problems of efficiency, duplication, and

jury understanding. The evidence of copyright and patent infringement, willfulness and damages

is too heavily intertwined to permit an efficient division of witnesses and documents for trial

presentation. Accordingly, Oracle continues to oppose trifurcation or bifurcation.

Numerous legal issues in this case have overlapping factual predicates. For instance, to

establish indirect copyright and patent infringement, Oracle will introduce evidence showing that

Google intentionally induced or contributed to the infringing conduct of others. Much of this

same evidence will also be introduced to support a finding of willful infringement. Accordingly,

this evidence would have to be presented in all three of the Court’s proposed phases. In Phase

One, Google’s fair use and de minimis defenses to copyright infringement will require evidence

showing the amount and substantiality of Google’s copying and the effect of that copying upon

the potential market for and value of the copyrighted works. But that same evidence would need

to be repeated in the damages phase.

The Court’s comment that “evidence presented in an earlier phase can be used by counsel

and by the jury in a subsequent phase” may contemplate invoking earlier evidence without

recalling witnesses. But, as a practical matter, it is not clear how the relevant evidence could be

introduced in an earlier phase and then effectively re-used in a later phase without recalling the

witnesses needed to present it or permitting counsel to summarize the previous evidence relevant

to a subsequent phase. If the Court adheres to time limits along the lines previously imposed,

efficient presentation of evidence will be critical. Presenting evidence in a single phase would

better serve the jury, the Court, the witnesses, and the parties.

At the same time, Oracle acknowledges the Court’s concern about the length and

complexity of the jury instructions. Consequently, as an alternative to trifurcation, Oracle

proposes that all evidence be presented in a single phase, but the reading of jury instructions and

the jury’s deliberations be divided into separate phases on the three sets of issues proposed by the

Court. This would avoid the need to present witnesses and evidence more than once, but would

still help the jury by dividing the instructions and deliberations into more digestible segments.

1

II. LEGAL STANDARD

Pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 42(b), a court may order a separate trial of

any claim or issue “[f]or convenience, to avoid prejudice, or to expedite and economize.” Fed. R.

Civ. P. 42(b). “In the Ninth Circuit, [b]ifurcation . . . is the exception rather than the rule of

normal trial procedure.” GEM Acquisitionco, LLC v. Sorenson Group Holdings, LLC, No. C 09-

01484 SI, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 50622, at *7 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 27, 2010) (citation omitted).

Courts consider several factors in deciding whether to separate a trial into multiple phases:

“whether the issues are clearly separable, and whether bifurcation would increase convenience

and judicial economy, reduce the risk of jury confusion, and avoid prejudice to the parties.” Id.

at *4-5 (citation omitted).

III. THE COPYRIGHT, PATENT, WILLFULNESS, AND DAMAGES ISSUES

IN THIS CASE ARE NOT CLEARLY SEPARABLE

The issues of copyright liability, patent liability, damages, and willfulness in this case are

not clearly separable. The factual predicates for Oracle’s direct and indirect infringement claims,

Google’s defenses, willfulness, and damages overlap to such a degree that trifurcation would be

inefficient, impractical, unhelpful to the jury, and potentially prejudicial to Oracle.

For example, numerous internal Google documents on Android’s architecture (relevant to

infringement) also discuss aspects of the Java platform and reveal Google’s knowledge of the

need for a Java license (relevant to willfulness and damages). The same Google witnesses who

will testify about the development of Android (infringement) also have information about the

Java licensing discussions (willfulness and damages) and the commercial success of Android

(damages). The same Sun/Oracle witnesses who testify about Java’s copyrighted features

(copyright infringement) will also testify about Java’s patented features (patent infringement) and

about the harm to Java caused by Android (fair use and damages).

In short, most of the major factual subjects in the case are relevant to two or more of the

Court’s proposed phases. To present its case effectively, Oracle would need to call many of the

twenty-four witnesses on its will-call list twice or even three times. The following chart identifies

2

major subjects and fact witnesses (several of them third-party witnesses) that are likely to come

up in two or more phases:

3

4

A few specific examples will help illustrate the difficulty of witness presentation posed by

the Court’s trifurcation plan:

(1) Dr. Mark Reinhold, Chief Java Architect at Sun and now Oracle, was involved in the

development of the Java virtual machine and Java class libraries and APIs. He would testify in

the proposed copyright phase regarding the importance of the core Java class libraries and APIs

and the creativity and work that went into them; in the proposed patent phase about the Java

technology in the asserted patents; and in the proposed damages/willfulness phase about the

importance of the innovations represented by the copyrighted material and patented technology.

If Oracle were to elicit his patent-related testimony when he first appears in the copyright phase,

the jury could be confused about its relevance. Unless Oracle were permitted to fully explain and

address the patents in that first phase, the jury would not be able to understand the testimony or

appreciate its significance. Similarly, if Dr. Reinhold were to testify about the economic

importance of the copyrights and patents to Sun and Oracle in the first phase, the jury could be

confused as to the relevance of that testimony to their liability-only deliberations following the

first phase, and might not appreciate the evidence when it later deliberates on damages. These

problems could possibly be reduced by having counsel provide refreshers prior to or during each

phase, but proceeding in that manner would be inefficient and less effective. The only other

5

option would be to call Dr. Reinhold three times, a substantial burden on the witness and an

inefficient use of the jury’s time.

(2) Joshua Bloch, a Java engineer who left Sun to work on Android for Google, is

expected to offer testimony about the Java APIs, the value and creativity of those APIs, and

Google’s copying of Java APIs and code into Android. This testimony would need to be

presented in the copyright phase under the Court’s proposed plan. Mr. Bloch is also expected to

provide testimony relating to whether Google’s infringement was willful or intentional—that

testimony would fall into the willfulness/damages phase. Finally, Mr. Bloch may have testimony

relevant to the ’476 patent, which covers security features incorporated in the Java security APIs

that Mr. Bloch helped develop. That testimony would be presented in the patent phase. Thus,

Mr. Bloch would need to appear three times or be subject to the same refreshers or summaries

discussed above.

(3) Andy Rubin, the head of Google’s Android division, is expected to testify about, inter

alia, Google’s decision to base Android on Java and Google’s negotiations with Sun for a Java

license. The first subject will be highly relevant to Phases One and Two on copyright and patent

infringement, while the second subject is relevant to all phases including the willfulness and

damages phase.

Given the extensive overlap of facts relevant to all three of the proposed phases, neither

the legal nor factual issues are “clearly separable” such that trifurcation would be warranted:

1. Liability and Willfulness Are Not Separable: The facts underlying Oracle’s claims

for indirect copyright and patent infringement and willfulness significantly overlap. To establish

indirect infringement of copyrights and patents, Oracle must show that Google intentionally

induced or contributed to direct infringement by third parties. See Global-Tech Appliances, Inc.

v. SEB S.A., 131 S. Ct. 2060, 2066-67 (2011); Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster,

Ltd., 545 U.S. 913, 930-31 (2005). The intent requirement, at least with respect to the patents,

may be satisfied by showing that Google was “willfully blind” to the fact that Oracle had

protective patents. See Global-Tech, 131 S. Ct. at 2067, 2070-71. Similar evidence would be

introduced in the copyright phase. See A & M Records, Inc. v. Napster, 239 F.3d 1004, 1020 (9th

6

Cir. 2001) (“Contributory liability requires that the secondary infringer ‘know or have reason to

know’ of direct infringement”).

That same evidence would also be introduced in the willfulness phase. “[A] willful

determination . . . is a finding of fact inextricably bound to the facts underlying the alleged

infringement.” WeddingChannel.com, Inc. v. The Knot, Inc., No. 03 Civ. 7369 (RWS), 2004 U.S.

Dist. LEXIS 25749, at *6 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 23, 2004) (denying motion to separate trials on issues

of liability and damages); see also Kos Pharms., Inc. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 218 F.R.D. 387, 393

(S.D.N.Y. 2003) (“questions regarding infringement and willfulness cannot always be neatly

disaggregated into distinct evidentiary foundations grounded on entirely different witnesses and

documents”). The Ninth Circuit recently confirmed that “willful blindness” also establishes

willfulness in the copyright context. See, e.g., Louis Vuitton Malletier, S.A. v. Akanoc Solutions,

Inc., 658 F.3d 936, 944 (9th Cir. 2011) (“To prove ‘willfulness’ under the Copyright Act, the

plaintiff must show (1) that the defendant was actually aware of the infringing activity, or (2) that

the defendant’s actions were the result of ‘reckless disregard’ for, or ‘willful blindness’ to, the

copyright holder’s rights”). The standard for willfulness in the patent context is similar. To

decide whether Google willfully infringed Oracle’s patents, the jury must consider whether

Google acted “despite an objectively high likelihood that its actions constituted infringement of a

valid patent.” In re Seagate Tech., LLC, 497 F.3d 1360, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (en banc).

The evidence of Google’s intent to induce or contribute to infringement by others is the

same evidence that will support a finding of willfulness. Oracle expects to rely on the same

Google witnesses (including Rubin, Bloch, Lee, Lindholm, and Swetland) and much of the same

documentary evidence to show that Google willfully copied Java technology despite its

knowledge of the intellectual property rights covering Java. In particular, the history of Google’s

licensing negotiations with Sun and Oracle and the numerous internal Google documents

indicating Google’s awareness that it needed a Java license will be presented to support Oracle’s

indirect infringement and willfulness cases.

The evidence presented in the liability and willfulness phases will overlap even more if

the Court allows Google to present evidence of its equitable defenses (waiver, estoppel, laches,

7

implied license) to the jury during the liability phases of the trial. Since the Court decides

equitable defenses, Oracle opposes the submission of these matters to the jury, even for an

advisory verdict. See Oracle’s Memo on Jury Instructions, at 81 (ECF No. 538). But if such

evidence is allowed, then Oracle must be allowed to present evidence to counter it, further

blurring the distinctions among the phases. See Haworth, Inc. v. Herman Miller, Inc., No. 1:92

CV 877, 1993 WL 761974, at *3-4 (W.D. Mich. July 20, 1993) (willfulness to be tried in liability

phase along with defendant’s equitable defenses since proof of willful infringement could provide

a basis for the plaintiff to negate the defendant’s equitable defenses); Wang Labs., Inc. v.

Mitsubishi Elecs. Am., Inc., No. CV 92-4698 JGD, 1994 WL 471414, at *2 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 3,

1994), aff’d on other grounds, 103 F.3d 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (willfulness bears on equitable

estoppel defense and thus should be tried with liability).

For example, Google argues that the equitable defenses apply because Oracle’s

predecessor in interest, Sun Microsystems, waived its rights by purportedly failing to pursue

Google for violation of the Java intellectual property. In response, Oracle will present evidence

that Sun and Google engaged in ongoing licensing negotiations, Sun never waived any claims

related to Google’s violations, and Google never could have reasonably believed it had an

“implied license.” This same evidence is also relevant to willfulness and would be presented in

that context as well.

At the October case management conference, Google acknowledged that the evidence it

intends to offer in support of its equitable defenses overlaps with willfulness. See Oct. 19, 2011

Hearing Transcript at 55-56 (ECF No. 553). In opposing Oracle’s proposal to file a motion for

summary judgment of the equitable defenses, Google argued that the motion would not save any

trial time because, “[t]he same evidence is going to come in on willfulness or the claim of willful

blindness, or on our defense of fair use, which is a jury question, not a court question, all kinds of

things.” Id.

Additionally, Google’s willful infringement of the Java intellectual property negates its

equitable defenses, as a matter of law. “[T]he infringer’s state of mind can support a finding of

egregious conduct, thereby defeating equitable defenses such as laches.” WeddingChannel.com,

8

2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25479, at *7. Thus if Google is allowed to present evidence of its

equitable defenses during the proposed two liability phases, Oracle should be allowed to present

the evidence of Google’s willful conduct at that time.

Even if the Court decides to pursue its trifurcation plan, willfulness should be tried as part

of the liability phases (where the facts overlap the most) rather than in the damages phase.

2. Liability and Damages Are Not Separable: Courts have recognized that because

liability and damages are generally overlapping subjects, they should be divided only in

exceptional situations. “It is precisely because the issue of willfulness, liability and damages

generally overlap that bifurcation remains the exception in patent cases, rather than the rule.”

Lutron Elecs. Co., Inc. v. Crestron Elecs., Inc., No. 2:09 cv 707 DB, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

49623, at *5 (D. Utah May 19, 2010) (declining to bifurcate multi-defendant trial with five

patents concerning “difficult engineering concepts”); In re Sortwell, Inc., No. C 08-05167 JW,

2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 121618, at *5-6 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 12, 2011) (declining to bifurcate liability

from damages because evidence relating to liability and evidence relating to damages

overlapped).

Witness testimony and documentary evidence on the core features of the Java platform are

highly relevant to both the liability case and damages calculation. The history of the Java

licensing discussions between Google and Sun/Oracle will be presented as evidence supporting a

finding of infringement. That history is also relevant to damages—to establish the starting point

for the hypothetical negotiation and to substantiate the losses that Sun/Oracle sustained as a result

of Android’s unlicensed use of Java intellectual property.

Furthermore, Google’s fair use and de minimis defenses to copyright infringement (which

would be tried in the copyright phase) will involve evidence that is also directly relevant to

damages. Among the statutory factors considered in evaluating a fair use defense are “the

purpose and character of the use;” “the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to

the copyrighted work as a whole;” and “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or

value of the copyrighted work.” 17 U.S.C. § 107. See also Elvis Presley Enters. v. Passport

Video, 349 F.3d 622, 630 (9th Cir. 2003) (weighing four Section 107 factors in affirming entry of

9

preliminary injunction). Similarly, Google’s de minimis defense is based on its claim that its

copying was insubstantial and unimportant. Newton v. Diamond, 388 F.3d 1189, 1193 (9th Cir.

2003) (analyzing whether unauthorized use of copyrighted composition was substantial enough to

sustain infringement claim). But the evidence of the significance of Google’s copying and its

impact on the potential market for and value of Java intellectual property is also the foundation

for Oracle’s copyright infringement damages case. Under the Court’s proposed plan, Oracle

would have to present this evidence twice as well.

3. Copyright and Patent Liability Are Not Separable: Oracle’s copyright and patent

claims both arise from Google’s incorporation of Java technology into Android. The evidence of

Google’s copyright and patent infringement will be delivered by the same witnesses and through

many of the same documents. For the jury to fully comprehend the evidence in a phased trial, the

witnesses would need to testify separately in each of the two liability phases. Dr. Reinhold, for

instance, and other Sun/Oracle engineers and executives possess information on both copyright

and patent-related subjects and are expected to testify as to both.

Similarly, the same team of Google engineers that copied the copyrighted Java API

specifications and source code into Android (Bloch, Lee, Bornstein, McFadden, Swetland) also

implemented the patented features of Java in Android. Oracle expects to call these witnesses to

testify as to both copyright and patent issues. In addition to these factual witnesses, Oracle’s

technical expert, Dr. John Mitchell, will offer testimony on both copyright and patent issues.

It would not suffice for the witnesses to appear only in the first phase and deliver all of

their testimony at once. If the first phase is devoted exclusively to copyright liability, patentrelated

testimony in that phase would be difficult or impossible for the jury to comprehend. By

the time the patent phase commenced, the jury might struggle to recall and isolate the pertinent

patent-related testimony from the first phase. To effectively present testimony in a phased trial,

the parties would have to present the relevant witnesses in each phase.

10

IV. TRIFURCATION WILL PREJUDICE ORACLE AND INCONVENIENCE

THE WITNESSES AND JURY

Separating the presentation of evidence into multiple phases would prejudice Oracle and

greatly inconvenience the witnesses, the jury and the Court. If the parties are not permitted to

recall witnesses in subsequent phases, juror memory attrition would become an issue, particularly

if the deliberations between the phases go long. See A.L. Hansen Mfg. Co. v. Bauer Prods., Inc.,

No. 03 C 3642, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 8935, at *16 (N.D. Ill. May 17, 2004) (“[T]he more time

taken between trial phases, the greater the risk of losing jurors or having their memory fade

before evaluating the totality of the circumstances”). In such a case, Oracle would be forced to

select and repeat the key evidence in subsequent phases in order to ensure that the jury continues

to consider the relevant evidence. The memory attrition issue becomes particularly acute given

that this is a technical case where the jury is unlikely to fully comprehend or appreciate the

significance of the patent evidence if Oracle is required to introduce it during the copyright phase

of trial.

However, if witnesses appear more than once, that would consume the jury’s time hearing

duplicative testimony and would be burdensome to the witnesses themselves—particularly the

third-party witnesses. For example, because damages-related evidence such as the history of the

licensing negotiations and the extent of Google’s copying from Java will overlap the liability

evidence, division of liability and damages would also be inefficient.

Finally, a three-phase trial will likely promote additional disputes because with so much

overlap, the parties will disagree over which evidence can properly be presented in each phase.

Oracle expects these disputes would generate significant additional briefing for the parties and the

Court, result in delays, and thus further inconvenience the jury throughout the trial.

V. ORACLE’S PROPOSED ALTERNATIVE: A SINGLE TRIAL WITH

PHASED JURY DELIBERATIONS

For the foregoing reasons, Oracle opposes bifurcation or trifurcation of the trial. As an

alternative, in view of the Court’s concerns about lengthy and confusing jury instructions if the

trial is not divided into phases, Oracle proposes that the Court allow the parties to present the case

in its entirety in one phase. The Court would then instruct the jury in phases and the jury would

11

deliberate each phase before receiving instructions for the next. This alternative approach would

obviate the need to present the same witnesses and documentary evidence multiple times, while

giving the jury a more limited set of facts to find during each deliberation phase.

Dated: November 18, 2011

MICHAEL A. JACOBS

KENNETH A. KUWAYTI

MARC DAVID PETERS

DANIEL P. MUINO

MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP

By: /s/ Michael A. Jacobs

Michael A. Jacobs

Attorneys for Plaintiff

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

12

628

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.,

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.,

Defendant.

Case No. 3:10-cv-03561-WHA

GOOGLE’S RESPONSE TO PROPOSED

TRIAL PLAN

Judge: Hon. William Alsup

In its October 26, 2011 Order (Dkt. No. 564), the Court proposed a trifurcated jury trial

and invited counsel to critique its proposed trial plan. Google agrees with the Court that the trial

should be trifurcated into three phases, with copyright liability in phase one, patent liability in

phase two, and damages and willfulness in phase three. The Court’s proposal would reduce the

likelihood of juror confusion and is more likely to lead to a just result than a non-trifurcated trial.

Google also renews its request for a stay of the patent case pending completion of the

reexamination proceedings. Those proceedings are actively affecting the scope of this litigation.

For example, the PTO recently closed prosecution proceedings for the ’720 patent with rejections

on all of the asserted claims of that patent, which represent almost a quarter of the patent claims

asserted in this case. And throughout the reexamination proceedings, Oracle has been forced to

change the scope of its patent claims, making unambiguous arguments for a narrow construction

of certain claim terms as well as amending and adding new claims. The patent case should be

stayed to allow the reexamination proceedings to run their course so that this Court’s

proceedings are not merely duplicative of PTO activity or, worse, unnecessary. Should the Court

decline to stay the patent case, Google requests that the Court allow the parties to videotape livewitness

testimony in the copyright case (phase one) and present that evidence by videotape in

subsequent phases, if necessary, in order to minimize the burden a trifurcated trial might impose

upon witnesses, especially third parties not affiliated with Google or Oracle.

A. A trifurcated trial is the most practical and efficient way to try this case.

“For convenience, to avoid prejudice, or to expedite and economize, the court may order

a separate trial of one or more separate issues [or] claims[.]” Fed. R. Civ. P. 42(b). The trial

court has broad discretion in deciding how to manage the trial, including whether to sever issues

or claims. See M2 Software, Inc. v. Madacy Entm’t, 421 F.3d 1073, 1088 (9th Cir. 2005);

Netflix, Inc. v. Blockbuster, Inc., C 06-02361 WHA, 2006 WL 2458717 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 22,

2006); Bates v. United Parcel Serv., 204 F.R.D. 440, 448 (N.D. Cal. 2001); Arnold v. United

Artists Theater Circuit, Inc., 158 F.R.D. 439, 458 (N.D. Cal. 1994); Gardco Mfg., Inc. v. Herst

Lighting Co., 820 F.2d 1209, 1212 (Fed. Cir. 1987).

In determining whether to sever claims for trial, courts consider a variety of factors.

1

These factors include whether such severing would: (1) reduce the complexity of the case or

increase juror comprehension, (2) result in significant delay or redundancy in the trial, or (3)

prejudice either party. See, e.g., Arnold, 158 F.R.D. at 458; Ciena Corp. v. Corvis Corp., 210

F.R.D. 519, 521 (D. Del. 2002); WeddingChannel.Com, Inc. v. The Knot, Inc., 03 CIV. 7369

(RWS), 2004 WL 2984305 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 23, 2004); Real v. Bunn-O-Matic Corp., 195 F.R.D.

618, 621 (N.D. Ill. 2000). In this case, all of these factors support trifurcation.

1. A trifurcated trial would reduce complexity and increase juror

comprehension.

Severing claims or issues for trial is a well-established method of managing complex

patent cases. See, e.g., Ciena Corp., 210 F.R.D. at 521 (noting that “bifurcation of complex

patent trials has become common”); Smith v. Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., 538 F. Supp. 977,

984 (D. Del. 1982) (finding “that one trial of both issues [i.e., liability and damages] would tend

to clutter the record and to confuse the jury.”). “Experienced judges use bifurcation and

trifurcation both to simplify the issues in patent cases and to maintain manageability of the

volume and complexity of the evidence presented to a jury.” Ciena Corp., 210 F.R.D. at 521

(quoting Thomas L. Creel, Bifurcation, Trifurcation, Opinions of Counsel, Privilege and

Prejudice, 424 PLI/Pat 823, 826 (1995)); see also Manual for Complex Litigation (Fourth) §

33.27 (2004) (“Bifurcation of a patent jury trial or a phased trial considering major issues

separately can sometimes assist in properly focusing the jury’s attention”).

This case plainly is complex. Concepts like “application programming interfaces” and

“virtual machines” will be foreign to most jurors. The sheer breadth of the case adds to the

complexity. Oracle’s patent case alone involves 26 claims of six unrelated patents. Oracle

proposes 59 jury instructions. Its verdict form includes 110 questions of fact for the jury. The

joint exhibit list is 161 pages long and lists thousands of potential exhibits. It is unreasonable to

expect a jury to digest all of this information over the course of a single, colossal, multi-week

trial. And it is no wonder that the Court repeatedly has urged Oracle to narrow the claims to a

manageable number for trial. (See, e.g., Dkt. Nos. 131 and 458.) Oracle simply refuses to do so.

Trifurcating the case into three phases would reduce complexity by allowing the jurors to

2

focus on only those issues relevant to a particular phase. Ciena Corp., 210 F.R.D. at 521 (noting

that trifurcation can “enhance jury decision making in two ways: (1) by presenting the evidence

in a manner that is easier for the jurors to understand, and (2) by limiting the number of legal

issues the jury must address at any particular time.” (quoting Steven S. Gensler, Bifurcation

Unbound, 75 Wash. L. Rev. 705, 751 (2000))). For example, in the copyright phase, the jury

will not need to hear evidence of what the patent claims are, how the claim terms have been

construed, or how the Dalvik virtual machine works—none of which are relevant to the

copyright issues. By narrowing the scope of the issues the jury must consider at any given time,

trifurcation would increase overall juror comprehension and lead to a more just result than in a

non-trifurcated trial.

2. A trifurcated trial would not result in significant delay or redundancy.

A trifurcated trial would not result in significant redundancy in the presentation of

evidence or argument, nor would it significantly lengthen the overall trial time, because all three

phases would be tried to the same jury. See Laitram Corp. v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 791 F.

Supp. 113, 117-18 (E.D. La. 1992) (ordering a “single trial” to proceed in “three separate and

distinct phases” before the same jury); see also Joy Techs., Inc. v. Flakt, Inc., 772 F. Supp. 842,

849 (D. Del. 1991) (noting possibility of bifurcating issues into “separate phases of a single

trial”). As the Court noted in its October 26, 2011 Order (Dkt. No. 564): “All evidence

presented in an earlier phase can be used by counsel and by the jury in a subsequent phase as

relevant to the issues then on trial.” Most background narrative evidence—the identity of the

parties, the history of Java, the general purpose of Android—likely would need to be presented

to the jury only once. Any redundancy that might result from the parties’ need to re-present

more specific or more complicated evidence would be offset by the gains in juror comprehension

that would result from a trifurcated proceeding in which the issues are more focused. See In re

Innotron Diagnostics, 800 F.2d 1077, 1084 (Fed. Cir. 1986) (“In deciding whether one trial or

separate trials will best serve the convenience of the parties and the court, avoid prejudice, and

minimize expense and delay, the major consideration is directed toward the choice most likely to

result in a just final disposition of the litigation.”)

3

3. A trifurcated trial would not prejudice the parties.

In assessing the risk of prejudice, the Court should consider two types of prejudice: first,

the prejudice that may arise from juror confusion if severance is denied; and second, prejudice

caused by delay that might result from severance. Real, 195 F.R.D. at 621. As discussed above,

a trifurcated trial would reduce the likelihood of juror confusion. Trifurcation therefore

reduces—not creates— the first type of prejudice. And trifurcation would not significantly delay

the trial of this action. Severing the case would crystallize the issues for the jurors and allow

them to understand complex facts faster and with greater ease. Thus, by trying all necessary

phases in seriatim to a single jury, the case can be presented as expeditiously as it could be in a

single, sprawling, unitary trial. Thus, a trifurcated trial would not prejudice the parties.

Accordingly, and for all the foregoing reasons, Google agrees with the Court’s proposal

for a trifurcated trial as described in the Court’s October 26, 2011 Order (Dkt. No. 564).

B. The PTO’s reexamination proceedings are actively affecting the scope of this case

and the patent trial should be stayed pending completion of those proceedings.

The primary trial management problem in this case is Oracle’s refusal to narrow its patent

claims to a reasonable number for trial. The PTO’s reexamination proceedings, however, have

narrowed (and will continue to narrow) the scope of some of the asserted claims. Accordingly,

the Court should stay the patent case pending completion of the reexamination proceedings.

As explained in Google’s October 4, 2011 Case Management Statement (Dkt. No. 480),

reexamination proceedings may significantly reduce the number of claims to be tried in this case.

Just two days ago, the PTO examiner closed prosecution for the ’720 patent, with rejections on

all asserted claims. The PTO’s rejection of the asserted claims of the ’720 patent is significant—

according to Oracle’s damages expert, “the ’720 patent alone would be approximately 10%

[$20.2 million] of the aggregate (portfolio) reasonable royalty” Oracle seeks. These claims of

the ‘720 patent represent almost a quarter of Oracle’s asserted patent claims for trial. In total,

almost two-thirds of the asserted patent claims Oracle intends to try in this case have been

rejected.1

_____________________________

1 The PTO has yet to issue an office action on the six claims of the ’104 patent. As for the other patents, 80% of the claims as to which the PTO has issued an office action have been rejected.

4

Even if the asserted patent claims are not ultimately rejected in the reexamination

process, the reexamination proceedings will affect the scope of the claims to be tried in this case.

Indeed, the reexamination proceedings already have resulted in a narrowing of some of Oracle’s

asserted claims.2

That is because, in the reexamination proceedings, Oracle has made

unambiguous arguments for a narrow construction of certain claim terms. Oracle’s narrowing

arguments act as an immediately effective disavowal of any broader scope for those claims, even

if the claims are not ultimately amended. See Marine Polymer Techs, Inc. v. HemCon, Inc., 659

F.3d 1084, 2011 WL 4435986, *5 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (“[W]e have consistently held that arguments

made to the PTO on reexamination can create an estoppel or disavowal and thereby change the

scope of claims even when the language of the claims did not change.”).

Oracle has made the following narrowing arguments in the reexamination proceedings:

- That the claims of the ’702 patent require that the “multi-class file” contain the same

bytecodes as the original “class files.” (USPTO Reexam Control No. 90/011,492,

Response to Office Action at 20 (Sept. 6, 2011)).

- That the term “an instruction” as used in the claims of the ’520 patent refers to

exactly one instruction rather than one or more instructions (USPTO Reexam Control

No. 90/011,489, Interview Summary (Aug. 4, 2011)).

These arguments limit the scope of the claims to be tried in this case. See Marine Polymer, 2011

WL 4435986, *6 (“[I]f the scope of the claims actually and substantively changed because of

Marine Polymer’s arguments to the PTO, the claims have been amended by disavowal or

estoppel and intervening rights apply. This is so even though Marine Polymer did not amend the

language of its claims on reexamination.”). Further narrowing of claims likely will occur as the

reexamination proceedings progress. Accordingly, in order to conserve judicial resources and

____________________________

2

At the October 19, 2011 case management conference, the Court noted that only 11 percent of

all claims ultimately get rejected in reexamination proceedings. The more relevant statistic for

assessing the utility of a stay, however, is the number of claims that are cancelled or changed as

a result of reexamination proceedings. In ex parte reexamination proceedings 76% of all claims

are ultimately cancelled or changed. United States Patent and Trademark Office, Reexamination

Filing Data, September 30, 2011, available at

http://www.uspto.gov/patents/stats/Reexamination_Information.jsp. In inter partes

reexamination proceedings, the number is even higher: 89% of all claims ultimately are

cancelled or changed in the reexamination process. Id. The reexamination proceedings for the

patents at issue in this case are of both types—the proceedings for the ’720 and ’205 patents are

inter partes; the proceedings for the ’702, ’476, ’104, and ’520 are ex parte.

5

avoid duplication in this court of the PTO’s efforts in the reexamination proceedings, the Court

should stay the patent case pending completion of the reexamination proceedings.3

C. The Court should allow the parties to videotape testimony from the copyright trial

and replay that videotape, if necessary, in subsequent phases.

If the Court declines to stay the patent trial, the Court should allow the parties to

videotape live-witness testimony from the copyright trial (phase one) and replay that testimony,

as needed, in subsequent phases. Doing so will ensure fairness to the parties and minimize the

burden on party and nonparty witnesses whose testimony may be relevant to all three phases of

the trial.

Both Google and Oracle intend to call several witnesses whose testimony likely will be

relevant to all three phases of a trifurcated trial. Many of these witnesses are senior executives

with extremely busy schedules or third parties who may be unwilling or unable to testify three

different times. Rather than forcing these witnesses to remain “on call” throughout three trial

phases—or, in the case of third-party witnesses, risking their unavailability for one or more

phases—Google proposes that the Court allow the parties to videotape live witness testimony

from the copyright phase and replay that evidence, as necessary, in subsequent phases. Doing so

will minimize the burden on party and nonparty witnesses, while still allowing the parties to represent

certain evidence that jurors are unlikely to recall from a previous trial phase.

Dated: November 18, 2011

KEKER & VAN NEST LLP

By: s/ Robert A. Van Nest

ROBERT A. VAN NEST

Attorneys for Defendant

GOOGLE INC.

____________________________

3 Any delay in the completion of the reexamination proceedings is a product of Oracle’s own

doing. Oracle has requested several extensions of time—USPTO Reexam Control Nos.

95/001,560 (Apr. 29, 2011), 90/011,521 (July 15, 2011), and 90/011,492 (July 5, 2011)—and has

filed each response on the final day possible. Moreover, in one reexamination proceeding,

Oracle actually added claims, which could delay further the issuance of a final office action.

(USPTO Reexam Control No. 95/001,548, Amendment (Oct. 19, 2011)). Oracle’s tactics in the

reexamination proceedings belie any argument that a stay of the patent case pending completion

of those proceedings would somehow prejudice Oracle by delaying its right to relief.

6

|

|

|

|

| Authored by: designerfx on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 09:46 AM EST |

| please post yer corrections hear. [ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: designerfx on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 09:47 AM EST |

newspicks discussion here, please link the article referenced

if it is the first/top post on the subject.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: designerfx on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 09:49 AM EST |

comes documents here. Please post em in plain old text and

include the HTML formatting[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: designerfx on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 09:50 AM EST |

| off topic discussion here. [ Reply to This | # ]

|

- just to start off, 4th amendment district ruling - Authored by: designerfx on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 09:57 AM EST

- Hacker Shows How to Easily Root the Kindle Fire - Authored by: hardmath on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 11:38 AM EST

- Kindle gets rid of pink slips - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 03:32 PM EST

- ‘We had no evidence for anti-piracy law’, UK government admits - Authored by: N_au on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 07:22 PM EST

- His Billness on the stand - Authored by: SpaceLifeForm on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 08:19 PM EST

- Ice Creme Sandwich Review (slashgear) a very complete look at this. - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 09:25 PM EST

- No News is Good News - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 09:55 PM EST

- Blatant Profiteering From Thailand Floods? - Authored by: sproggit on Tuesday, November 22 2011 @ 01:40 AM EST

- EFF to the Rescue ! - Authored by: Anonymous on Tuesday, November 22 2011 @ 05:29 AM EST

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 11:15 AM EST |

What we have here is a bunch of lawyers and judges who

understand nothing about computers. They don't want their

ignorance to show, so they assume that any content in the

patent that does not make sense to them must be really deep

and really important. Ick.

There is nothing in these patents. Nothing. I read the

highlighted phrases and shake my head. Patents on *that*?!?

The highlighted phrases are either long-winded buzzword

filled recitations of trivial programming constants, or

simply meaningless phrases altogether.

How can ANYONE think there is anything here to argue over?

I don't understand this. Are all the lawyers and judges and

patent examiners crazy?[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Ian Al on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 11:55 AM EST |

Nope, sorry, I've changed my mind after seeing the helpful, colour-coded

charts.

I could manage the trifurcated trial, especially with the video highlights. Only

by separating patents and copyrights would I be sure which argument and which

facts went with which topic and which law.

The charts show me nothing. I would have to rely on the judge to tell me who won

what. It's not s'posed to work like that!

---

Regards

Ian Al

Software Patent: code for Profit![ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 12:09 PM EST |

I am still puzzled why a Jury Trail is going to decide over

some factual definitions. Unless the Jury is selected based

on actual knowledge in the matter how can they possible

decide? It is a bit like voting or discussing on the shape of

a circle; but since it is round there should only be one

possible outcome of the vote?

--confused[ Reply to This | # ]

|

- Why a Jury Trial? - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 01:34 PM EST

| |

| Authored by: amster69 on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 01:39 PM EST |

I will be amazed if 12 good citizens are able to get any where near to

understanding this case(s). It is hard enough for me (a techie) reading these

notes in my home and trying to grasp all the fine details.

For a non-techie sitting in a court room and also being distracted by the circus

acts of the various lawyers... Nope, it just ain't gonna happen.

---

Bob[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: AntiFUD on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 02:08 PM EST |

Mark, could you possibly enlighten an ignoramus, such as me, what exactly

"Reference No. 1 for anticipation purposes" and "Reference No. 2

for anticipation purposes" means/refers to in the Judge's instruction re

the highlighted patent claim handouts?

Could you also explain where the 'anticipation' from the Plaintiff's perspective

comes into play?

Thanks in advance.

---

IANAL - Free to Fight FUD - "to this very day"

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: softbear on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 03:24 PM EST |

Starting with the very first example of the '205, I have nothing but contempt

for this patent, and by extension the system that allowed it.

Tokenization of keywords was done in Level 2 BASIC on the TRS-80 Model 1. That's

over 30 years ago. There is nothing in this claim that was not in use at that

time.

---

IANAL, etc.

[ Reply to This | # ]

|

- This is PATENTED? - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 03:45 PM EST

- Ah Bliss - Authored by: complex_number on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 05:10 PM EST

- Ah Bliss - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 11:27 PM EST

- Tokenization - Authored by: Anonymous on Tuesday, November 22 2011 @ 03:35 PM EST

- This is PATENTED? - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 04:11 PM EST

- Commodore PET 1977 - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 04:53 PM EST

- Tokenization goes back to the early 50's - Authored by: jesse on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 05:07 PM EST

- This is PATENTED? - Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 08:18 PM EST

- The claim has nothing to do with tokenization of keywords - Authored by: bugstomper on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 11:35 PM EST

- This is PATENTED? - Authored by: Anonymous on Tuesday, November 22 2011 @ 11:04 AM EST

| |

| Authored by: Anonymous on Monday, November 21 2011 @ 03:43 PM EST |

| for those that wish to avoid reading patent claims. [ Reply to This | # ]

|

|

|

|

|