|

|

| Lodsys - Lodsys in a Panic to Keep Apple Out of Suit |

|

|

Monday, August 29 2011 @ 09:00 AM EDT

|

Oh what a tangled web we weave,

When first we practise to deceive!

Sir Walter Scott, Marmion, Canto vi. Stanza 17.

Scottish author & novelist (1771 - 1832)

In the latest filing by Lodsys [PDF] in response to the Apple motion to intervene in the Lodsys v. Combay case, Lodsys gives every indication it is in a panic to keep Apple from intervening. Much of the document is redacted, but despite that fact we can glean the sense that Apple's entry into the lawsuit spoils Lodsys's entire theory of the litigation, at least with respect to the Apple (and likely Google) developers.

To try and make sense out of Lodsys's reply we need to go back to

Apple's original motion [PDF] and working our way through the Lodsys response [PDF], Apple reply [PDF], and Lodsys sur-reply [PDF].

What are Apple's arguments for why it should be allowed to intervene?

- Apple is licensed to the asserted patents, has embodied the technology covered by those patents in Apple's products and services it provides to the defendant developers, and the protection of that license extends to those developers.

- Apple satisfies the requirements for intervention as of right under Fed R. Civ. P Rule 24(a). Apple has an interest in the property that is the subject of this action, namely, the patents in suit. Apple has a license to those very same patents. The value of this license to Apple here lies in Apple’s ability, pursuant to the express terms of the license, to offer products and services embodying the patents in suit to the Developers, in return for the Developers’ agreement to pay Apple a percentage of their sales made using Apple’s products and services.

- [E]ven if Apple could not intervene as of right, the motion should still be granted for the separate reason that Apple satisfies the requirements for permissive intervention under Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 24(b). It is black-letter law that permissive intervention is appropriate to protect the interests of a non-party whose technology has been accused of patent infringement.

Apple supports each of the last two contentions above with extensive legal citations.

In essence, Apple is arguing that the Lodsys patented technologies are embedded in the Apple offerings and merely utilized for their intended purpose by developers in building their applications, not independently infringed by the developer applications themselves. Importantly, Lodsys has publicly acknowledged that Apple is, in fact, licensed to the patents. Moreover, the claim charts that Lodsys sent to defendants specifically identify Apple technology as the basis for the infringement, not the developers' separate technology.

In its initial response Lodsys tries sleight of hand, focusing on the trivial and non-responsive while ignoring the bigger picture presented by Apple. For example, ignoring Apple's contentions under the license, Lodsys tries to contend that it is not the license that is important but the fact that Apple's interest is purely economic (because Apple will lose revenue). While the impact on Apple will certainly have an economic element, Lodsys disregards Apple's property interest in the patents in the form of the license.

Lodsys then attacks Apple's position on the grounds that Apple lacks standing, i.e., Apple lacks a sufficiently substantial interest in the patents to bring a counterclaim. But Lodsys is confused on the law. Were Apple trying to assert its non-exclusive license against a third-party, Lodsys would be correct. But Apple is asserting its rights under the license against the patent holder, the party ultimately responsible for having granted those rights. Apple does not require an exclusive license to do so. The mere existence of a non-exclusive license in that context is sufficient for standing to bring the counterclaim.

Lodsys next argues that it should be granted the right to conduct discovery on the Apple license in order to establish that the license doesn't grant whatever rights Apple claims. This is an interesting argument from the standpoint that Lodsys goes on and on about Apple's (legitimate) right to maintain the terms of the license agreement as confidential. How is it that the present patent holder (Lodsys) in acquiring the rights to the patents did not acquire from its predecessor in interest in the patents (Webvention) a copy of all licenses that encumber those patents? Maybe Lodsys should be crying to Webvention instead of to the court.

Finally, Lodsys argues that Apple is under no obligation to indemnify the app developers and, for that reason, should not be permitted to intervene. For that proposition Lodsys fails to cite a single relevant case.

This failure by Lodsys to properly address any of the key Apple assertions is what Apple focuses on in its reply to Lodsys's response. For example, Apple points out that Lodsys never addresses the issue of where the infringement lies - in the Apple technology as Apple contends or in the developer technology.

Apple points out that Lodsys's arguments for discovery on the license prior to an order permitting Apple's intervention is not the law; such discovery may only occur after the grant of intervention. Apple further notes that Lodsys's arguments that Apple's motion is premature are also not supported by the law (and, of course, if Apple were to wait to intervene, Lodsys would argue that they are too late).

By the time we get to the Lodsys sur-reply, it comes across as legal gibberish. For example, Apple shouldn't be allowed to protect its property interest in the license and intervene because one of the current defendants is certain to challenge the validity of the patents. Say what?!!!

Lodsys then appears to argue that it is not a licensor under the license to Apple and therefore has no privity of contract with Apple justifying Apple's intervention. Again, that position flies in the face of the law. Lodsys took the patents subject to Apple's license and, for that reason, is bound by the license regardless of whether Lodsys's name actually appears on the face of the license.

I don't usually like to predict outcomes on motions, but I will go out on a limb here and predict that Apple is granted the right to intervene if for no other reason than Lodsys appears to be clueless with respect to the law.

****************

Docket - Lodsys v. Combay

06/17/2011 - 9 - APPLICATION to Appear Pro Hac Vice by Attorney George M Newcombe for Apple, Inc. (APPROVED FEE PAID) 6-3600. (ch, ) (Entered: 06/17/2011)

06/17/2011 - 10 - APPLICATION to Appear Pro Hac Vice by Attorney Jonathan C Sanders for Apple, Inc. (APPROVED FEE PAID) 6-3599. (ch, ) (Entered: 06/17/2011)

06/17/2011 - 11 - E-GOV SEALED SUMMONS Issued as to Combay, Inc., Iconfactory, Inc., Illusion Labs AB, Michael G. Karr d/b/a Shovelmate, Quickoffice, Inc., Richard Shinderman, Wulven Game Studios. (Attachments: # 1 Iconfactory, # 2 Illusion Labs, # 3 Michael Karr, # 4 Quickoffice, # 5 Shindermann, # 6 Combay)(ehs, ) (Entered: 06/17/2011)

06/21/2011 - 12 - ORDER granting 5 Motion to Seal Document Exhibit A to the Declaration of Jonathan C. Sanders in Support of Apple's Motion to Intervene shall be maintained under seal. Signed by Judge T. John Ward on 6/21/2011. (ch, ) (Entered: 06/21/2011)

06/21/2011 - 13 - ***FILED IN ERROR. PER ATTORNEY. PLEASE IGNORE.*** MOTION for Extension of Time to File Response/Reply to Apple Inc's Motion to Intervene by Lodsys, LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Text of Proposed Order)(Huck, Christopher) Modified on 6/22/2011 (ch, ). (Entered: 06/21/2011)

06/22/2011 ***FILED IN ERROR. PER ATTORNEY Document # 13, Motion for Extension of Time. PLEASE IGNORE.*** (ch, ) (Entered: 06/22/2011)

06/22/2011 - 14 - MOTION for Extension of Time to File Response/Reply to Apple Inc.'s Motion to Intervene by Lodsys, LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Text of Proposed Order)(Huck, Christopher) (Entered: 06/22/2011)

06/27/2011 - 15 - ORDER granting 14 Motion for Extension of Time to File Response/Reply re 4 MOTION to Intervene Responses due by 7/27/2011. Signed by Judge T. John Ward on 6/27/2011. (ch, ) (Entered: 06/27/2011)

07/08/2011 - 16 - E-GOV SEALED SUMMONS Returned Executed by Lodsys, LLC. Michael G. Karr d/b/a Shovelmate served by CM RRR on 6/30/2011, answer due 7/21/2011; Quickoffice, Inc. served on 6/30/2011, answer due 7/21/2011. (Attachments: # 1 Quickoffice)(ehs, ) (Entered: 07/08/2011)

07/11/2011 - 17 - E-GOV SEALED SUMMONS Returned Executed by Lodsys, LLC. Iconfactory, Inc. served on 7/5/2011 by CM RRR on Registered Agent, answer due 7/26/2011. (ehs, ) (Entered: 07/11/2011)

07/12/2011 - 18 - Defendant's Unopposed First Application for Extension of Time to Answer Complaint re Iconfactory, Inc.(Findlay, Eric). (Entered: 07/12/2011) 07/12/2011 Defendant's Unopposed First Application for Extension of Time to Answer Complaint is GRANTED pursuant to Local Rule CV-12 for Iconfactory, Inc. to 8/25/2011. 30 Days Granted for Deadline Extension.( sm, ) (Entered: 07/12/2011)

07/14/2011 - 19 - E-GOV SEALED SUMMONS Issued as to Illusion Labs AB. (ch, ) (Entered: 07/14/2011)

07/15/2011 - 20 - NOTICE of Attorney Appearance by Melissa Richards Smith on behalf of Apple, Inc. (Smith, Melissa) (Entered: 07/15/2011)

07/15/2011 - 21 - NOTICE of Attorney Appearance by Charles Craig Tadlock on behalf of Quickoffice, Inc. (Tadlock, Charles) (Entered: 07/15/2011)

07/15/2011 - 22 - Defendant's Unopposed First Application for Extension of Time to Answer Complaint re Quickoffice, Inc. (to 8/20/2011).(Tadlock, Charles) (Entered: 07/15/2011) 07/15/2011 Defendant's Unopposed First Application for Extension of Time to Answer Complaint is GRANTED pursuant to Local Rule CV-12 for Quickoffice, Inc. to 8/20/2011. 30 Days Granted for Deadline Extension.( sm, ) (Entered: 07/15/2011)

07/18/2011 - 23 - Defendant's Unopposed First Application for Extension of Time to Answer Complaint re Michael G. Karr d/b/a Shovelmate.(Findlay, Eric). (Entered: 07/18/2011)

07/18/2011 Defendant's Unopposed First Application for Extension of Time to Answer Complaint is GRANTED pursuant to Local Rule CV-12 for Michael G. Karr d/b/a Shovelmate to 8/20/2011. 30 Days Granted for Deadline Extension.( sm, ) (Entered: 07/18/2011)

07/18/2011 - 24 - ***FILED IN ERROR. PLEASE IGNORE.*** E-GOV SEALED SUMMONS Returned Executed by Lodsys, LLC. Richard Shinderman served on 6/7/2011 by CM RRR, answer due 6/28/2011. (ehs, ) Modified on 7/18/2011 (ch, ). (Entered: 07/18/2011) 07/18/2011

Answer Due Deadline Updated for Richard Shinderman.(ch, ) (Entered: 07/18/2011)

07/18/2011 - 25 E-GOV SEALED SUMMONS Returned Executed by Lodsys, LLC. Richard Shinderman served on 7/7/2011, answer due 7/28/2011. (ch, ) (Entered: 07/18/2011) 07/18/2011 ***FILED IN ERROR. WRONG DATE ADDED Document # 24, Sealed Summons. PLEASE IGNORE.*** (ch, ) (Entered: 07/18/2011)

07/21/2011 - 26 - AMENDED COMPLAINT For Patent Infringement against Combay, Inc., Iconfactory, Inc., Illusion Labs AB, Michael G. Karr d/b/a Shovelmate, Quickoffice, Inc., Richard Shinderman, Wulven Game Studios, filed by Lodsys, LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit, # 2 Exhibit)(Huck, Christopher) (Entered: 07/21/2011)

07/26/2011 - 27 - NOTICE by Apple, Inc. re 4 MOTION to Intervene - Supplemental Declaration of Jonathan C. Sanders in Further Support of Apple Inc.'s Motion to Intervene - (Attachments: # 1 Affidavit - Declaration of Jonathan C. Sanders, # 2 Exhibit A to Declaration of Jonathan C. Sanders, # 3 Exhibit B to Declaration of Jonathan C. Sanders)(Smith, Melissa) (Entered: 07/26/2011)

07/27/2011 - 28 - ***FILED IN ERROR PER ATTORNEY. SEE CORRECTED DOCUMENT # 29 *** RESPONSE in Opposition re 4 MOTION to Intervene filed by Lodsys, LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Text of Proposed Order)(Huck, Christopher) Modified on 7/27/2011 (ehs, ). (Entered: 07/27/2011)

07/27/2011 - 29 - ***REPLACES DOCUMENT # 28 WHICH WAS FILED IN ERROR*** REDACTED RESPONSE in Opposition re 4 MOTION to Intervene filed by Lodsys, LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Declaration in Support of Opposition, # 2 Text of Proposed Order)(Huck, Christopher) Modified on 7/27/2011 (ehs, ). Modified on 7/28/2011 (sm, ). (Entered: 07/27/2011)

07/27/2011 ***FILED IN ERROR PER ATTORNEY. Document # 28, response. PLEASE IGNORE.*** (ehs, ) (Entered: 07/27/2011)

07/27/2011 - 30 - SEALED RESPONSE to Motion re 4 MOTION to Intervene filed by Lodsys, LLC. (Huck, Christopher) (Entered: 07/27/2011)

07/28/2011 NOTICE FROM CLERK re 29 Response in Opposition to Motion. Clerk has modified entry to reflect that this document (response) is a REDACTED version. (Complete version filed separately under seal) (sm, ) (Entered: 07/28/2011)

07/28/2011 - 31 - Additional Attachments to Main Document: 30 Sealed Response to Motion.. (Attachments: # 1 Declaration in Support of Opposition, # 2 Text of Proposed Order)(Huck, Christopher) (Entered: 07/28/2011)

07/29/2011 - 32 - NOTICE by Lodsys, LLC of Dismissal of Defendant Richard Shinderman without Prejudice (Huck, Christopher) (Entered: 07/29/2011)

08/01/2011 - 33 - E-GOV SEALED SUMMONS Issued as to Combay, Inc.. (ch, ) (Entered: 08/01/2011)

08/03/2011 - 34 - Summons Returned Unexecuted by Lodsys, LLC as to Combay, Inc.. Summons returned unclaimed and returned to sender on 7/21/11 (ehs, ) (Entered: 08/03/2011)

08/08/2011 - 35 - REPLY to Response to Motion re 4 MOTION to Intervene - Apple Inc.'s Redacted Reply In Support of Motion to Intervene - filed by Apple, Inc.. (Smith, Melissa) (Entered: 08/08/2011)

08/08/2011 - 36 - SEALED REPLY to Response to Motion re 4 MOTION to Intervene filed by Apple, Inc.. (Smith, Melissa) (Entered: 08/08/2011)

08/09/2011 - 37 - NOTICE by Atari Interactive, Inc., Electronic Arts Inc., Quickoffice, Inc., Square Enix Ltd. re 4 MOTION to Intervene (Statement in Support of Apple's Motion to Intervene) (Barsky, Wayne) (Entered: 08/09/2011)

08/16/2011 - 38 - Second MOTION for Extension of Time to File Answer by Quickoffice, Inc.. (Attachments: # 1 Text of Proposed Order)(Tadlock, Charles) (Entered: 08/16/2011)

08/18/2011 - 39 - SEALED SURREPLY TO REPLY TO RESPONSE to Motion re 4 MOTION to Intervene filed by Lodsys, LLC. (Huck, Christopher) (Entered: 08/18/2011)

08/18/2011 - 40 - SUR-REPLY to Reply to Response to Motion re 4 MOTION to Intervene filed by Lodsys, LLC. (Huck, Christopher) (Entered: 08/18/2011)

08/19/2011 - 41 - Unopposed MOTION for Extension of Time to File Answer re 26 Amended Complaint, or Otherwise Respond by Michael G. Karr d/b/a Shovelmate. (Attachments: # 1 Text of Proposed Order)(Findlay, Eric) (Entered: 08/19/2011)

08/22/2011 - 42 - E-GOV SEALED SUMMONS Issued as to Atari Interactive, Inc., (Attachments: # 1 Electronics Arts Inc, # 2 Take-Two Interactive Software Inc)(ch, ) (Entered: 08/22/2011)

08/23/2011 - 43 - ORDER granting 41 Motion for Extension of Time to Answer. Michael G. Karr d/b/a Shovelmate be given to and including September 21, 2011 to answer. Signed by Judge T. John Ward on 8/23/11. (ehs, ) (Entered: 08/23/2011)

08/23/2011 - 44 - Answer Due Deadline Updated for Michael G. Karr d/b/a Shovelmate to 9/21/2011. (ehs, ) (Entered: 08/23/2011)

08/23/2011 - 45 - ORDER granting 38 Motion for Extension of Time to Answer. Quickoffice, Inc. has until August 29, 2011 in which to answer. Signed by Judge T. John Ward on 8/23/11. (ehs, ) (Entered: 08/23/2011) 08/23/2011 Answer Due Deadline Updated for Quickoffice, Inc. to 8/29/2011. (ehs, ) (Entered: 08/23/2011)

08/24/2011 - 46 - Unopposed MOTION for Extension of Time to File Answer re 26 Amended Complaint, or Otherwise Respond by Iconfactory, Inc.. (Attachments: # 1 Text of Proposed Order)(Findlay, Eric) (Entered: 08/24/2011)

08/24/2011 - 47 - ORDER granting 46 Motion for Extension of Time to Answer. Dft Iconfactory Inc deadline is extended to 9/26/2011. Signed by Judge T. John Ward on 8/24/2011. (ch, ) (Entered: 08/24/2011) 08/24/2011 Answer Due Deadline Updated for Iconfactory, Inc. to 9/26/2011. (ch, ) (Entered: 08/24/2011)

****************

Document 4 - Apple's Motion to Intervene with Attachments

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

MARSHALL DIVISION

LODSYS, LLC,

Plaintiff,

v.

COMBAY, INC.;

ICONFACTORY, INC.;

ILLUSION LABS AB;

MICHAEL G. KARR D/B/A SHOVELMATE;

QUICKOFFICE, INC.;

RICHARD SHINDERMAN;

WULVEN GAME STUDIOS,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION NO. 2:11-cv-272-TJW

HEARING REQUESTED

APPLE INC.’S MOTION TO INTERVENE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION .................................................. 1

FACTS AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND.......................... 3

I. The Licensed Technology ............................................. 3

II. Lodsys’s Infringement Claims .................................... 4

III. Early Stage of the Proceedings and Apple’s Proposed Answer and

Counterclaim .......................................... 6

ARGUMENT ...................................................... 7

I. Legal Standard ................................................... 7

II. Apple is Entitled to Intervene As a Matter of Right Under Rule 24(a)(2) ............. 8

A. Apple’s Motion to Intervene is Timely ....................................................... 9

B. Apple Has a Significant Interest in the Property and Transactions That

Are at Issue in this Lawsuit ..................................................... 10

C. Apple’s Ability to Protect its Interests Will Be Impaired if it is Not

Permitted to Intervene Here ............................................ 11

D. The Developers May Not Adequately Represent Apple’s Interest in

Demonstrating That Lodsys’s Infringement Claims Are Exhausted ........ 12

III. In The Alternative, Permissive Intervention is Appropriate Here Under Rule

24(b) ..................................................... 14

CONCLUSION ..................................................... 15

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

FEDERAL CASES

Bush v. Viterna,

740 F.2d 350 (5th Cir. 1984) ............................................................ 13

Chandler & Price Co. v. Brandtjen & Kluge, Inc.,

296 U.S. 53 (1935) ............................................... 11

Codex Corp. v. Milgo Elec. Corp.,

553 F.2d 735 (1st Cir. 1977) ............................................................... 12

Edwards v. City of Houston,

78 F.3d 983 (5th Cir. 1996) ............................................................ 7, 9, 10

GE Co. v. Wilkins,

2011 WL 533549 (E.D. Cal. Feb. 11, 2011) ................................................. 10

Heaton v. Monogram Credit Card Bank,

297 F.3d 416 (5th Cir. 2002) ...................................................... 9, 12, 13

Honeywell Int’l v. Audiovox Commc’ns Corp.,

2005 WL 2465898 (D. Del. May 18, 2005) .................................. 11, 12, 14

IBM Corp. v. Conner Periphs., Inc.,

1994 WL 706208 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 13, 1994) ........................................ 11

John Doe No. 1 v. Glickman,

256 F.3d 371 (5th Cir. 2001) ....................................................... 12, 13

LG Elecs. Inc. v. Q-Lity Comp. Inc.,

211 F.R.D. 360 (N.D. Cal. 2002) ......................................................... 14

Mendenhall v. M/V Toyota Maru No. 11 v. Panama Canal Co.,

551 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1977) ........................................................ 8

Negotiated Data Solutions, LLC v. Dell, Inc.,

No. 2:06-cv-528 (E.D. Tex. 2008) .................................................. 8–9

Ozee v. Am. Council on Gift Annuities, Inc.,

110 F.3d 1082 (5th Cir. 1997) ...................................................... 10

Reid v. GM Corp.,

240 F.R.D. 257 (E.D. Tex. 2006) .......................................... 7, 14–15

Sierra Club v. Espy,

18 F.3d 1202 (5th Cir. 1994) ..................................................... 7, 10

ii

Sierra Club v. Glickman,

82 F.3d 106 (5th Cir. 1996) ............................................... 9

Stallworth v. Monsanto Co.,

558 F.2d 257 (5th Cir. 1977) .......................................................... 7–8

State Farm Fire and Cas. Co. v. Black & Decker, Inc.,

Civ. A. 02-1154, 2003 WL 22966373 (E.D. La. Dec. 11, 2003) ....................................... 8

Teague v. Bakker,

931 F.2d 259 (4th Cir. 1991) .................................................... 13

Tegic Commc’ns Corp. v. Bd. Of Regents of the Univ. of Tex. Sys.,

458 F.3d 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2006).................................................. 11

The Aransas Project v. Shaw,

2010 WL 2522415 (S.D. Tex. June 17, 2010) ............................................ 9

TiVo Inc. v. AT&T Inc.,

No. 2-09-cv-259 (E.D. Tex. March 31, 2010) ............................................ 15

Trbovich v. United Mine Workers of Am.,

404 U.S. 528 (1972) ................................................................. 12

U.S. Ethernet Innovations, LLC v. Acer, Inc. et al,

No. 6:09-cv-448 (E.D. Tex. May 10, 2010) ........................................... 11, 15

FEDERAL RULES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 .................................................... 7

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Wright & Miller, FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE § 1914 (2d ed. 1986) ............................... 8

iii

Apple Inc. (“Apple”) hereby respectfully moves to intervene as a defendant and

counterclaim plaintiff in the above-captioned action brought by plaintiff Lodsys, LLC

(“Lodsys”) against seven software application developers (collectively, “Developers”), for

allegedly infringing U.S. Patent Nos. 7,222,078 (the “’078 patent”) and 7,620,565 (the “’565

patent” and, collectively, the “patents in suit”). Apple seeks to intervene because it is expressly

licensed to provide to the Developers products and services that embody the patents in suit, free

from claims of infringement of those patents.

INTRODUCTION

In its Complaint, Lodsys alleges that the Developers infringe the patents in suit.

Lodsys’s claims are based on the Developers’ use of products and services provided to the

Developers by Apple, for which the Developers pay Apple a percentage of their sales. Apple has

an interest in property that is at the center of this dispute, namely, its license to the patents in suit

and its business with the Developers, which depends on their use of products and services that

Apple is expressly licensed under the patents in suit to offer them. Both Lodsys’s Complaint and

its threats to other Apple developers adversely affect the value of Apple’s license and its

business with the Developers.

Apple should be permitted to intervene here, for at least two separate and

independent reasons. First, Apple satisfies the requirements for intervention as of right under

Fed R. Civ. P Rule 24(a). Apple has an interest in the property that is the subject of this action,

namely, the patents in suit. Apple has a license to those very same patents. The value of this

license to Apple here lies in Apple’s ability, pursuant to the express terms of the license, to offer

products and services embodying the patents in suit to the Developers, in return for the

Developers’ agreement to pay Apple a percentage of their sales made using Apple’s products and

services. The Developers, in turn, are able to use the products and services Apple provides to

them free from claims of infringement of the patents in suit under the doctrines of exhaustion and

first sale. Apple has a direct and substantial interest in preserving the value of its license, as well

as in protecting the value of its technology, services, and relationships with the Developers.

Those interests will be prejudiced absent intervention here. A determination that the Developers

are not permitted to use Apple’s licensed products and services will significantly diminish the

value of Apple’s license rights, impair its relationships with the Developers, and lead to loss of

significant revenue from all developers. In fact, the mere allegation of the same significantly

threatens to diminish Apple’s rights and those relationships. Moreover, Apple’s rights will not

be adequately protected by the current defendants in this case, because Lodsys has chosen to

assert these claims against Developers who are individuals or small entities with far fewer

resources than Apple and who lack the technical information, ability, and incentive to adequately

protect Apple’s rights under its license agreement.

Second, even if Apple could not intervene as of right, the motion should still be

granted for the separate reason that Apple satisfies the requirements for permissive intervention

under Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 24(b). It is black-letter law that permissive intervention is appropriate

to protect the interests of a non-party whose technology has been accused of patent infringement.

Apple’s proposed defense and counterclaim are based on the doctrines of exhaustion and first

sale deriving from Apple’s license to the patents in suit. Apple’s defense and claim present

numerous issues of law and fact that will be common to the main action, regardless of whether

Apple is permitted to intervene. Finally, intervention will not delay these proceedings or

prejudice any current party. The Court should grant this motion and allow Apple to file the

proposed Answer and Counterclaim submitted herewith.1

___________________

1 Apple’s proposed Answer and Counterclaim is attached as Exhibit A hereto.

2

FACTS AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

I. The Licensed Technology

Apple designs and offers a comprehensive ecosystem of technologies and services

that enable the delivery of software applications (or “Apps”) such as games, tools, and

educational services on Apple devices such as the Mac, iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch. See, e.g.,

Answer-in-Intervention (“Answer”) ¶ 1. In order to access Apple hardware and software, the

Developers use Apple application program interfaces (“APIs”), Apple software development kits

(“SDKs”), and Apple’s operating system (“iOS”). Id. ¶ 5. Together, these Apple products and

services permit the Developers to interact with Apple end users through the App Store, where

Developer Apps can be purchased or upgraded. Id. Apple also provides a comprehensive set of

Apple hosting, marketing, sales, agency and delivery services that allow Developers to provide

Apps to millions of Apple end users. See generally id.2 In return for Apple’s provision of these

products and services to the Developers, the Developers agree to pay Apple a percentage of their

sales made using Apple’s products and services. See, e.g., id. ¶ 6. Apple’s innovative products

and services have enjoyed great success: fourteen billion Apps have been downloaded from the

App store, and the App Store’s offerings grow daily, with 425,000 Apps available from tens of

thousands of unique app developers. Id.

To protect its enormous investment in its App Store and related hardware,

software, and APIs, Apple periodically enters into licenses for patents that allegedly cover Apple

technology, including one such license agreement (the “License”) that covers the patents-in-suit.

See generally Declaration of Jonathan C. Sanders (“Sanders Decl.”) ¶ 2, Ex. A. The License

____________________

2

The “App Store” is a virtual store from which users may buy and upgrade applications

such as games and tools. The developers, not Apple, set the prices at which their Apps

are sold. Apple acts as an agent of the Developers in effectuating the sale of the Apps to

Apple end users.

3

provides Apple with, among other things, the right to offer products and services that embody

the Lodsys patents. See generally id. Lodsys has acknowledged that Apple is licensed to these

patents. http://www.lodsys.com/blog.html (“Apple is licensed . . . .”) (emphasis in original).

II. Lodsys’s Infringement Claims

Although Lodsys’s Complaint lacks any detailed allegations as to what aspects of

the accused Apps infringe the patents in suit, notice letters Lodsys sent to each of the Developers

establish clearly that Lodsys’s claims target Apple technology. Specifically, the infringement

analysis in the notice letters focuses on the Developers’ use of Apple products and services

covered by the License.

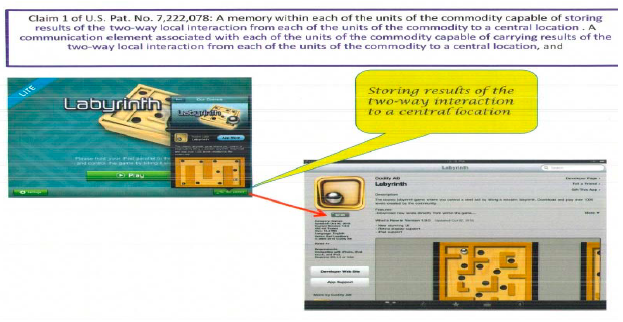

For example, Lodsys appended to its notice letters representative claim charts

purporting to show how Claim 1 of the ’078 patent (asserted here) reads on the accused products.

Sanders Decl. ¶ 3, Ex. B (Illusion Labs) at 4-9. Claim 1 of the ’078 patent claims, among other

things, (1) “[a] user interface, which is part of each of the units of the commodity, configured to

provide a medium for two-way local interaction between one of the users and the corresponding

units of the commodity, and further configured to elicit, from a user, information about the user’s

perception of the commodity”; (2) “[a] memory within each of the units of the commodity

capable of storing results of the two-way local interaction from each of the units of the

commodity to a central location” and “[a] communication element associated with each of the

units of the commodity capable of carrying results of the two-way local interaction from each of

the units of the commodity to a central location”; and (3) “[a] component capable of managing

the interactions of the users in different locations and collecting the results of the interaction at

the central location.” Docket No. 1, Ex. B at Claim 1. Each of these elements requires, under

Lodsys’s apparent theories, the use of licensed Apple APIs, software, and/or hardware.

4

For example, the screenshot Lodsys used purportedly to establish the first claim

element above with respect to Illusion Labs shows an interface with an “App Store” button that

uses an Apple API and other Apple technology to allow interaction between the App, the user,

and the App Store:

Sanders Decl. ¶ 3, Ex. B at 7. Similarly, Lodsys relied on screenshots depicting the use of

Apple’s APIs and memory and the App Store purportedly to meet the second claim element,

storing user feedback to the App Store itself:

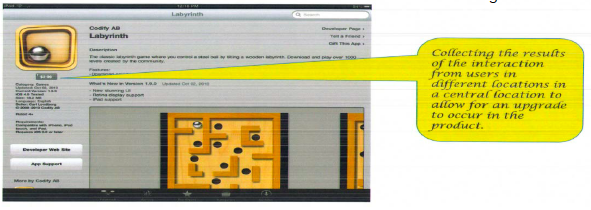

Id. at 8. Finally, Lodsys likewise pointed to a screenshot of the App Store itself to allegedly

meet the final claim element, collecting and storing the user results in that central location:

5

Id. at 9. Thus, in each case, even under Lodsys’s own infringement theories, Lodsys’s

allegations rest substantially or entirely on Apple products and services licensed under Apple’s

License, not on algorithms or content provided by the Developers themselves.

Moreover, even a cursory review of the diverse Apps accused of infringing the

patents in suit reveals that their only similarity is their use of Apple products and services. The

accused products range from business software that permits the user to work on Microsoft Office

documents (Quickoffice), to a fantasy game (Shadow Era), to a game in which the user guides a

silver ball through a labyrinth (Labyrinth), to a game requiring the user to strategically eliminate

hearts that shoot daggers (Hearts and Daggers), to a program that facilitates the composition of

“Tweets” for Twitter (Twitterrific), to a poker game (Mega Poker). See generally Docket No. 1

(Complaint). The only thing these Apps have in common is their use of the Apple technology

that permits the Developers to interact with Apple end users through the App Store and other

Apple technology. In other words, what is at issue in this case is not the substantive code in

these varied programs, but rather each individual App’s use of Apple products and services, all

of which are licensed.

III. Early Stage of the Proceedings and Apple’s Proposed Answer and Counterclaim

On June 1, 2011, this case was assigned to Judge T. John Ward. Sanders Decl. ¶

4. An initial case management conference has not yet been scheduled, no defendant has

responded to the Complaint, no discovery has been conducted, and, indeed, nothing of

6

significance has happened in the lawsuit beyond Lodsys’s simple filing of the Complaint.

Sanders Decl. ¶ 5. Because Lodsys’s infringement allegations are based on Apple products and

services that are indisputably licensed, Apple moves to intervene in this lawsuit to protect its

interest in its License by asserting a defense and counterclaim that Lodsys’s claims against the

Developers are barred under the doctrines of exhaustion and first sale.

ARGUMENT

I. Legal Standard

Rule 24(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure governs intervention as a

matter of right, while Rule 24(b) governs permissive intervention. Fed. R. Civ. P. 24. Pursuant

to Rule 24(a), a movant may intervene as a matter of right whenever four requirements are met:

(1) the motion is timely; (2) the movant has an interest relating to the property or transaction that

is the subject of the action; (3) the movant is situated such that the disposition of the action may,

as a practical matter, impair or impede its ability to protect its interest; and (4) the movant’s

interests are inadequately represented by the existing parties to the suit. Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a)(2);

Reid v. GM Corp., 240 F.R.D. 257, 259 (E.D. Tex. 2006). Although all four requirements must

be met, the inquiry is a “flexible one” that “focuses on the particular facts and circumstances

surrounding each application.” Edwards v. City of Houston, 78 F.3d 983, 999 (5th Cir. 1996);

see, e.g., Sierra Club v. Espy, 18 F.3d 1202, 1205 (5th Cir. 1994) (encouraging courts to allow

intervention “where no one would be hurt and the greater justice could be attained”) (citations

omitted).

Even where intervention as of right is not available, Rule 24(b) provides

separately and independently for permissive intervention whenever an applicant “has a claim or

defense that shares with the main action a common question of law or fact.” Fed. R. Civ. P.

24(b)(1)(B); see, e.g., Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F.2d 257, 269 (5th Cir. 1977) (explaining

7

permissive intervention). Where the applicant’s claim or defense is timely, shares a question of

law or fact with the main action, and will not prejudice any party, courts freely grant permissive

intervention. Id. (noting “liberal construction” of Rule 24(b)).

Finally, in evaluating a motion to intervene, the court must accept as true any

well-pleaded, non-conclusory allegations presented in the motion papers and proposed pleading.

Mendenhall v. M/V Toyota Maru No. 11 v. Panama Canal Co., 551 F.2d 55, 56 n.2 (5th Cir.

1977); see, e.g., State Farm Fire and Cas. Co. v. Black & Decker, Inc., Civ. A. 02-1154, 2003

WL 22966373, at *3 (E.D. La. Dec. 11, 2003) (“‘The pleading is construed liberally in favor of

the pleader and the court will accept as true the well pleaded allegations in the pleading.’”)

(quoting Wright & Miller, FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE § 1914 at 418 (2d ed. 1986)).

II. Apple is Entitled to Intervene As a Matter of Right Under Rule 24(a)(2)

The first reason this motion should be granted is that Apple is entitled to intervene

as of right. As set out further below, Apple’s motion is timely, Apple has a significant interest in

its License and in the licensed products and services that are the subject of this action, Apple’s

interests in that property may be substantially diminished if it is not permitted to intervene, and

the current defendants may not effectively represent Apple’s interests in this case. Negotiated Data Solutions, LLC v. Dell, Inc., No. 2:06-cv-528

(E.D. Tex. 2008), Intel filed a motion to intervene based on its license to the patents in suit.3

The

patents in suit had been assigned to plaintiff NDS, which had later filed an infringement action

against Intel customer Dell based on Intel components incorporated into Dell systems. Id. Intel

______________________

3 See generally Intel’s Complaint in Intervention, Negotiated Data Solutions, LLC v. Dell,

Inc., No. 2:06-cv-528 (E.D. Tex. 2008) (attached as Exhibit C to the Sanders Decl.).

8

sought to intervene and assert claims for a declaratory judgment that, among other things, the

plaintiff’s allegations were barred by the doctrine of patent exhaustion, id. at *6-*9, arguing that,

without declaratory relief, the plaintiff would “continue to wrongfully assert the Patents-in-Suit

against Dell and threaten Intel and its customers, thereby causing Intel irreparable injury and

damage.” Id. at *5-*7. The court found that Intel was entitled to intervene as a matter of right

on “the issues of patent exhaustion and licensing.” Order, Negotiated Data Solutions, LLC v.

Dell, Inc., No. 2:06-cv-528, at *1 (E.D. Tex. Oct. 23, 2008) (Everingham, J.) (attached as Ex. D

to the Sanders Decl.). As in Dell, Apple can easily satisfy each of the four requirements for

intervention as of right here.

A. Apple’s Motion to Intervene is Timely

A motion to intervene is timely where the intervenor promptly moves upon

learning of its interest in the litigation, where the current parties would not suffer prejudice from

allowing the intervention, and where no other special or unusual circumstances render the motion

untimely. See, e.g., Edwards, 78 F.3d at 1000; Heaton v. Monogram Credit Card Bank, 297

F.3d 416, 422-23 (5th Cir. 2002). Here, all requirements are readily satisfied. Indeed, Apple

moved while the case was still in its infancy: the lawsuit was filed just over a week ago, the

defendants have not yet answered Lodsys’s Complaint (indeed, upon information and belief, they

have not yet even been served with the summons and Complaint), and no other significant

developments have taken place. Apple’s motion is indisputably timely. See, e.g., Edwards, 78

F.3d at 1000-01 (noting that the Fifth Circuit has found motions filed several months into the

litigation timely as long as case is still in its early stages); The Aransas Project v. Shaw, 2010

WL 2522415, at *3 (S.D. Tex. June 17, 2010) (same); see also Sierra Club v. Glickman, 82 F.3d

106, 109 n.1 (5th Cir. 1996) (“The timeliness requirement only bars intervention applications

made too late.”).

9

Similarly, Apple’s motion will not result in prejudice to any existing party to this

action. Apple’s proposed Answer in Intervention asserts a single defense and declaratory

counterclaim, both based on the patent law doctrines of exhaustion and first sale. Based on

Lodsys’s infringement allegations, these very same issues will likely be raised by every

defendant. Therefore, allowing Apple to intervene will not cause any delay in the schedule, add

any new issues to the case, or otherwise affect the rights of the parties in any respect. Finally,

there are no special or unusual factors present that would render Apple’s motion untimely or

improper. See Edwards, 78 F.3d at 1000. Apple has thus satisfied this threshold requirement.

B. Apple Has a Significant Interest in the Property and Transactions That Are

at Issue in this Lawsuit

Apple has also met the second requirement for intervention as a matter of right

under Rule 24(a): an interest in the subject matter of the litigation that is “direct, substantial,

[and] legally protectable.” Ozee v. Am. Council on Gift Annuities, Inc., 110 F.3d 1082, 1096 (5th

Cir. 1997); Espy, 18 F.3d at 1207 (“[T]he ‘interest test’ is primarily a practical guide to disposing

of lawsuits by involving as many apparently concerned persons as is compatible with efficiency

and due process.”) (citations omitted). As set out above, Apple holds a license to the patents in

suit, the value of which depends on Apple’s ability to offer its licensed products and services to

the Developers in return for the Developers’ agreement to pay Apple. License rights such as

these are “protectable under the law” and provide a sufficiently close relationship to the litigation

to satisfy this requirement. See, e.g., GE Co. v. Wilkins, 2011 WL 533549, at *2 (E.D. Cal. Feb.

11, 2011) (“[Intervenor] has properly alleged that it has a license in the technology underlying

the ’985 Patent, and it is clear that such a license is protectable under the law.”).

Second, Lodsys’s infringement allegations target Apple’s own products and

services and their facilitation of communication between the end users, the Apps, the App Store,

10

and other Apple technology. Courts have consistently held that a legally sufficient interest is

implicated where infringement allegations rest on an intervenor’s own products or services. See,

e.g., Chandler & Price Co. v. Brandtjen & Kluge, Inc., 296 U.S. 53, 55 (1935) (holding that

manufacturer’s intervention in infringement action against its customers is “necessary for the

protection of its interest”); Tegic Commc’ns Corp. v. Bd. Of Regents of the Univ. of Tex. Sys.,

458 F.3d 1335, 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (“[T]o the extent that [interest of the manufacturer] may be

impaired by the Texas litigation, [manufacturer] may seek to intervene in that litigation.”);

Honeywell Int’l v. Audiovox Commc’ns Corp., 2005 WL 2465898, at *4 (D. Del. May 18, 2005)

(sufficient interest where intervenor made parts “at the heart” of infringement claims); IBM

Corp. v. Conner Periphs., Inc., 1994 WL 706208, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 13, 1994) (same).4

Finally, this litigation has fundamentally disrupted Apple’s relationships with the

Developers and with other developers, and places in jeopardy the revenue that Apple derives

from those relationships. The potential loss of revenue, developers, or goodwill provides yet

another independent basis upon which to find that Apple has a legally sufficient interest in the

property at issue. Cf., e.g., U.S. Ethernet Innovations, LLC v. Acer, Inc. et al., No. 6:09-cv-448,

at *4 (E.D. Tex. May 10, 2010) (Love, J.) (acknowledging significant interest in litigation based

on, inter alia, potential loss of customers and goodwill, but ultimately granting permissive

intervention without reaching question of intervention as of right) (Ex. E to the Sanders Decl.).

C. Apple’s Ability to Protect its Interests Will Be Impaired if it is Not Permitted

to Intervene Here

As set out above, Apple has demonstrated that its interests in the licensed

technology at issue will be impaired if it is not allowed to intervene. A finding that Lodsys is

_____________________

4 While indemnification obligations are sometimes at issue in cases under Rule 24(a), the

cases do not require or place any dispositive weight on any such obligation, as set out

above. And any such obligation is of course unnecessary for permissive intervention.

11

permitted to assert infringement claims against the Developers based on their use of licensed

Apple technology would effectively negate Apple’s license rights, as well as harm Apple’s

ability to preserve its substantial economic interest in its Developer relationships and sales of its

licensed products and services. See, e.g., Codex Corp. v. Milgo Elec. Corp., 553 F.2d 735, 738

(1st Cir. 1977) (explaining that a “manufacturer must protect its customers . . . in order to avoid

the damaging impact of an adverse ruling against its products”); Honeywell, 2005 WL 2465898,

at *4 (holding that intervenor can “rightly claim . . . its interests will be impaired” where product

is “at the heart” of the case). Moreover, an adverse outcome may harm Apple’s ability to protect

its license rights in future litigation involving Lodsys and any number of other App developers,

providing an independent basis on which to find Apple has satisfied this prong. See, e.g.,

Heaton, 297 F.3d at 424 (holding that potential negative stare decisis effect is also sufficient).

D. The Developers May Not Adequately Represent Apple’s Interest in

Demonstrating That Lodsys’s Infringement Claims Are Exhausted

Finally, it is hornbook law that Apple’s burden in demonstrating that the existing

defendants will not adequately represent its interests is “minimal,” and requires no more than a

showing that the representation by those parties “may be” insufficient. Trbovich v. United Mine

Workers of Am., 404 U.S. 528, 538 n.10 (1972); accord, e.g., John Doe No. 1 v. Glickman,

256 F.3d 371, 380 (5th Cir. 2001) (“The potential intervener need only show that the

representation may be inadequate.”) (emphasis in original) (citations omitted).

Apple has met this requirement for several separate and independent reasons.

First, the Developers lack the resources to fully and fairly litigate the issue of whether Lodsys’s

claims are exhausted. The Developers are largely individuals, see, e.g., Docket No. 1 ¶¶ 5, 7

(identifying two of seven defendants as individuals), or small entities with limited resources.

See, e.g., http://www.manta.com/c/mmj0mt2/the-iconfactory-inc (defendant Iconfactory has

12

about six employees); http://www.manta.com/c/mmlhs8p/combay-inc (approximately two

employees for defendant Combay). Apple’s far superior resources alone constitute a ground on

which to find its interests may not be adequately represented. See, e.g., Bush v. Viterna, 740

F.2d 350, 357 (5th Cir. 1984) (this prong is met when “it is clear that the applicant will make a

more vigorous presentation of arguments than existing parties”); Teague v. Bakker, 931 F.2d

259, 262 (4th Cir. 1991) (“Given the financial constraints on the insureds’ ability to defend the

present action, there is a significant chance that they might be less vigorous than the Teague

Intervenors in defending their claim to be insureds under the ERC policy.”).

Moreover, even if the financial disparity between the parties were not in and of

itself sufficient to meet this prong, the interests of Apple and the Developers in this litigation

may ultimately diverge. While the Developers will likely be interested in resolving this case as

quickly and inexpensively as possible, Apple’s interest is in protecting its broader license rights

with respect to thousands of App developers for Apple products who may be the subject of future

Lodsys lawsuits or threats. This constitutes an independent basis upon which to find that

Apple’s interests may not be adequately represented absent intervention. See, e.g., Doe, 256

F.3d at 380-81 (noting that disparity of incentives between party with “broad” interest in

resolving issue and more narrow interest of intervening entity supported granting motion to

intervene); Heaton, 297 F.3d at 425 (“That the FDIC’s interests and Monogram’s may diverge in

the future, even though, at this moment, they appear to share common ground, is enough to meet

the FDIC's burden on this issue.”) (intervention appropriate where existing party possessed broad

public interest and party seeking to intervene possessed narrower economic interest).

Finally, the Developers may lack sufficient information and expertise regarding

Apple’s license rights and the nature and operation of Apple’s licensed technology to adequately

13

represent Apple’s interests. Apple’s superior information constitutes a third separate reason to

find that the Developers’ defense may not be adequate to protect Apple’s license rights.

Honeywell, 2005 WL 2465898, at *4 (“[B]ecause [intervenor] is uniquely situated to understand

and defend its own product, its interests are not adequately represented by existing parties to the

litigation.”); LG Elecs. Inc. v. Q-Lity Comp. Inc., 211 F.R.D. 360, 365-66 (N.D. Cal. 2002).

III. In The Alternative, Permissive Intervention is Appropriate Here Under Rule

24(b)

Even if Apple did not meet the standard for intervention as of right, however, this

motion should still be granted because Apple’s proposed defense and counterclaim present

numerous questions of fact and law that are common to the existing lawsuit. First, based on the

infringement allegations Lodsys has made to date, it is clear that both Apple and the existing

defendants will raise issues of patent exhaustion and first sale, requiring the Court to analyze

Apple’s rights under its license, the licensed technology that Lodsys has accused of

infringement, and the application of the exhaustion and first sale doctrines to Lodsys’s claims.

Second, additional common questions of fact exist with respect to the licensed

Apple products and methods that Lodsys appears to be accusing of infringement. Precisely how

the Developers use Apple’s SDKs, APIs, memory, software, hardware, and servers, as well as

the App Store itself—and precisely how those Apple products and services work—will be

factual questions with respect to both Apple’s exhaustion defense and counterclaim and Lodsys’s

existing infringement claims against the Developers. Finally, the Court will effectively be

required to engage in the same claim construction and infringement analysis with respect to both

Lodsys’s existing claims and Apple’s exhaustion defense, including the same analysis of the

relevant claim terms, specifications, prosecution histories, and Lodsys infringement allegations.

14

Under these circumstances, courts uniformly find that permissive intervention is

appropriate. For example, in Reid, 240 F.R.D. at 260 (Folsom, J.), the court granted permissive

intervention to Microsoft where, as here, Microsoft’s software was claimed to be a substantial

part of the allegedly infringing system. In doing so, the court noted that “Microsoft’s claims and

defenses share common questions of law and fact with the action by Plaintiffs against

Defendants . . . . Microsoft’s claims of invalidity and unenforceability raise the same questions

of law and fact as similar claims by Defendants because they are all asserted against the ’120

patent.” Id.; accord, e.g., TiVo Inc. v. AT&T Inc., No. 2-09-cv-259 (E.D. Tex. March 31, 2010)

(Folsom, J.) (permissive intervention where infringement claims rested on software provided by

Microsoft) (Ex. F to Sanders Decl.); Acer, No. 6:09-cv-448 (Love, J.) (permissive intervention

where patents were asserted against Intel technology incorporated in customer devices).

As in each of these cases, Apple’s proposed pleading relates to the same patents,

claims, products, and defenses that will be litigated here regardless of whether Apple is allowed

to intervene. Similarly, as set out above, this motion is timely and will result in no prejudice to

the existing parties. Permissive intervention is thus appropriate.

CONCLUSION

For each of the foregoing reasons, Apple respectfully requests that the Court grant

Apple’s motion and permit the filing of Apple’s proposed Answer and Counterclaim.

15

Dated: June 9, 2011

Respectfully submitted,

By /s/ Eric H. Findlay

Eric H. Findlay

State Bar No. 00789886

FINDLAY CRAFT, LLP

6760 Old Jacksonville Hwy

Suite 101

Tyler, TX 75703

George M. Newcombe (pro hac pending)

Jonathan C. Sanders (pro hac pending)

SIMPSON THACHER & BARTLETT, LLP

2550 Hanover Street

Palo Alto, CA 94304

Counsel for Intervenor Defendant and

Counterclaim Plaintiff Apple Inc.

Document 29 - Lodsys Opposition to Apple's Motion to Intervene

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

LODSYS, LLC,

Plaintiff,

ATARI INTERACTIVE, INC.;

COMBAY, INC.;

ELECTRONIC ARTS INC.;

ICONFACTORY, INC.;

ILLUSION LABS AB;

MICHAEL G. KARR D/B/A SHOVELMATE;

QUICKOFFICE, INC.;

ROVIO MOBILE LTD.;

RICHARD SHINDERMAN;

SQUARE ENIX LTD.;

TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE,

INC.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION NO. 2:1 l-cv-272

PLAINTIFF LODSYS, LLC'S RESPONSE IN OPPOSITION TO

APPLE INC.'S MOTION TO INTERVENE

REDACTED VERSION

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

II. ARGUMENT

A. Threshold Matter:

1. As a Matter of Law,

2. At the Very Least, Apple's Motion Should Be Stayed Pending Discovery

B. Additional Threshold Matter: Apple's Motion is Premature

C. Apple is Not Entitled to Intervention as a Matter of Right Under Rule 24(a)

3. Apple's Motion is Untimely

4. Apple Lacks Any Direct, Substantial and Legally Protectable Interest

5. Apple's Purported Interest Will Not Be Impaired Absent Intervention

6. Apple's Purported Interest is More Than Adequately Represented

D. Apple is Not Entitled to Permissive Intervention Under Rule 24(b)

III. CONCLUSION

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Ace Capital v. Varadam Found.,

392 F. Supp. 2d 671 (D. Del. 2005)

Adams v. Consol. Wood Products Employee Ben. Plan,

No. 2:10-CV-310-TJW, 2011 WL 665821 (E.D. Tex. Feb. 14, 2011)

Bouchard v. Union Pac. R. Co.,

No. CIV .A.H-08-1156, 2009 WL 1506677 (S.D. Tex. May 28, 2009)

Bush v. Viterna,

740 F.2d 350 (5th Cir. 1984)

Butler, Fitzgerald & Potter v. Sequa Corp.,

250 F.3D 171 (2d Cir. 2001)

Dial v. P 'ship for Response & Recovery,

No. L09-CV-218, 2010 WL 1054884 (E.D. Tex. Feb. 23, 2010)

Edwards v. City of Houston,

78 F.3d 983 (5th Cir. 1996)

Fair child Semiconductor Corp. v. Power Integrations, Inc.,

630 F. Supp. 2d 365 (D. Del. 2007)

Flynn v. Hubbard,

782 F.2d 1084 (1st Cir. 1986)

Frazier v. Map Oil Tools, Inc.,

No. CIV .A.C-10-4, 2010 WL 2352056 (S.D. Tex. June 10, 2010)

Heaton v. Monogram Credit Card Bank of Georgia,

297 F.3d 416 (5th Cir. 2002)

Hopwood v. State,

No. CIV. A-92-CA-563-SS, 1994 WL 242362 (W.D. Tex. Jan. 20, 1994)

In re Babcock & Wilcox Co.,

No. CIV.A. 01-912, 2001 WL 1095031 (E.D. La. Sept. 18, 2001) Ingebretsen on Behalf Ingebretsen v. Jackson Pub. Sch. Dist.,

88 F.3d 274 (5th Cir. 1996)

Int'l Tank Terminals, Ltd. v. M/V Acadia Forest,

579 F.2d 964 (5th Cir. 1978)

Intel Corp. v. Broadcom Corp.,

Intellectual Prop. Dev., Inc. v. TCI Cablevision of California, Inc.,

248 F.3d 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2011)

IP Innovation L.L.C. v. Google, Inc.,

661 F. Supp. 2d 659 (E.D. Tex. 2009)

James v. Harris County Sheriff's Dept,

No. CIV.A. H-04-3576, 2005 WL 1878204 (S.D. Tex. Aug. 9, 2005)

John Doe No. I v. Glickman,

256 F.3d 371 (5th Cir. 2001)

Kneeland v. Nat 7 Collegiate Athlectic Ass 'n,

806 F.2d 1285 (5th Cir. 1987)

League of United Latin Am. Citizens, Council No. 4434 v. Clements,

884 F.2d 185 (5th Cir. 1989)

Lincoln Gen. Ins. Co. v. Aisha's Learning Ctr.,

No. CIV .A. 3:04-CV-0063B, 2004 WL 2533575 (N.D. Tex. Nov. 9, 2004)

Morrow v. Microsoft Corp.,

499 F.3d 1332 (Fed. Cir. 2007)

Negotiated Data Solutions, LLC v. Dell, Inc.,

No. 2:06-cv 528 (E.D. Tex. Oct. 23, 2008)

New Orleans Pub. Serv., Inc., v. United Gas Pipe Line Co.,

732 F.2d 452 (5th Cir. 1984)

Ortho Pharm. Corp. v. Genetics Inst., Inc.,

52 F.3D 1026 (Fed. Cir. 1995)

Ouch v. Sharpless,

237 F.R.D. 163 (E.D. Tex. 2006)

Ramirez v. Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Auth.,

28 F. Supp. 2d 1019 (W.D.Tex. 1998)

Rigco, Inc. v. Rauscher Pierce Refsnes, Inc.,

110 F.R.D. 180 (N.D. Tex. 1986)

Saldano v. Roach,

363 F.3d 545 (5th Cir. 2004)

S.E.C. v. Provident Royalties, LLC,

No. CIV. 3:09-CV-1238-L, 2010 WL 27185 (N.D. Tex. Jan. 5, 2010)

Shaunfield v. Citicorp Diners Club, Inc.,

No. 3:04-CV-1087-G, 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 11244 (N.D. Tex. June 8, 2005)

Shea v. Angulo,

19 F.3d 343 (7th Cir. 1994)

Sierra Club v. Epsy,

18 F.3d 1202 (5th Cir. 1994)

State v. Am Tobacco Co.,

No. 5-98CV-270, 1999 WL 1022129 (E.D. Tex. Nov. 5, 1999)

Taylor Communications Group, Inc. v. Sw. Bell Tel. Co.,

172 F.3d 385 (5th Cir. 1999)

Teague v. Bakker,

931 F.2d 259 (4th Cir. 1991)

Tivo Inc. v. AT&T Inc.,

2:09-cv-259 (E.D. Tex. Mar. 31, 2010)

U.S. Ethernet Innovations, LLC v. Acer, Inc. et al,

No. 6:09-cv-448 (E.D. Tex. May 10, 2010)

United States v. Microsoft Corp.,

No. CIV.A.98-1232(CKK), 2002 WL 319784 (D.D.C. Jan. 28, 2002)

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency (Lubbock Indep. Sch. Dist.),

138 F.R.D. 503 (N.D. Tex. 1991)

Vaupel Textilmaschinen KG v. Meccanica Euro Italia SPA,

944 F.2d 870 (Fed. Cir. 1991)

Villas at Parkside Partners v. City of Farmers Branch,

245 F.R.D. 551 (N.D. Tex. 2007)

Washington Elec. Co-op., Inc. v. Massachusetts Mun. Wholesale Elec. Co.,

922 F.2d 92 (2d Cir. 1990)

Plaintiff Lodsys, LLC ("Lodsys") respectfully submits this response in opposition to Apple Inc.'s Motion To Intervene [dkt. no. 4] (the "Motion").1

I. INTRODUCTION

Apple asserts that it is entitled to intervene based on the License. Apple also asserts that it might lose revenues absent intervention. And Apple asserts that the defendants are allegedly too small and without financial resources to adequately represent Apple's purported interest. But all of Apple's assertions are legally and factually without merit for several reasons.

First, although Apple's Motion is based on the License, Apple ignores [redacted]

Second, Apple's own Motion demonstrates that its purported interest is, at best, purely economic. For example, Apple repeatedly speculates that this action could "lead to loss of significant revenues from all developers." Motion at 2. But courts have consistently held that economic interests do not satisfy the requirements for intervention. Apple's prediction that this lawsuit may hurt its relationship with Developers and may diminish revenues is also too speculative and contingent to satisfy the requirements for intervention.

Third, Apple repeatedly asserts that the defendants are allegedly individuals or "small entities with limited resources." Motion at 12. But Apple prematurely filed its Motion before Lodsys filed its Amended Complaint [dkt. no. 26] against several large companies with substantial financial and technical resources, including Atari Interactive, Inc., Electronic Arts Inc. ("Electronic Arts"), Rovio Mobile Ltd. ("Rovio"), Square Enix, Ltd., and Take-Two

1Apple Inc. ("Apple") "seeks to intervene because it is expressly licensed." Motion at 1. Because Apple filed [redacted] (the "License") under seal, the portions of this response that quote or reference the License have been redacted. An un-redacted version of this response has also been filed under seal. A copy of the License filed under seal is attached as Exhibit A to the Declaration of Jonathan C. Sanders [dkt. no. 4-3] ("Sanders Decl.").

1

Interactive Software, Inc. Accordingly, there can be no serious dispute that the defendants will more than adequately represent Apple's purported interest.

In short, the Court has myriad bases for denying Apple's Motion, and the Court should do so now before any additional needless expense and judicial resources are wasted concerning a purported interest that [redacted]

II. ARGUMENT

"The movant bears the burden of establishing its right to intervene." Adams v. Consol. Wood Products Employee Ben. Plan, No. 2:10-CV-310-TJW, 2011 WL 665821, *4 (E.D. Tex. Feb. 14, 2011). As discussed in detail below, Apple fails to satisfy its heavy burden because (a) as a threshold matter, [redacted]

(b) as an additional threshold matter, Apple's Motion is premature; (c) Apple is not in entitled to intervention as a matter of right under Rule 24(a); and (d) Apple is not in entitled to permission intervention under Rule 24(b).

A. Threshold Matter:

[redacted] As a threshold matter, therefore, Apple's Motion should be denied. But

even assuming arguendo that [redacted], at the very least, Apple's

Motion should be stayed pending discovery concerning whether [redacted]2

1. As a Matter of Law, [redacted]

Apple asserts that its legally protectable interest — and the underlying basis for its request to intervene — derives from the License. See Motion at 1 ("Apple has an interest in the

2Apple alleges that, "[b]ecause Apple is licensed to offer products and services that embody the patents in suit to its

Developers, under the patent law doctrines of exhaustion and first sale, Developers are entitled to use, free from

claims of infringement of the patents in suit." Proposed Answer at |8. Accepting Apple's allegations as true for

purposes of Apple's Motion only, Lodsys does not challenge here Apple's assertions regarding the scope of the

license grant {i.e., [redacted]); rather, this response focuses only on

whether [redacted] Lodsys reserves all rights to challenge all of Apple's assertions, if

Apple is permitted to intervene.

2

property that is at the center of this dispute, namely, its license to the patents in suit...."). A patent, however, is "a bundle of rights which may be divided and assigned, or retained in whole or part." Vaupel Textilmaschinen KG v. Meccanica Euro Italia SPA, 944 F.2d 870, 875 (Fed. Cir. 1991). "[P]arties are free to assign some or all patent rights as they see fit based on their interests and objectives." Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. v. Power Integrations, Inc., 630 F. Supp. 2d 365, 372 (D. Del. 2007) (citing Morrow v. Microsoft Corp., 499 F.3d 1332, 1348 n.8 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

"To determine whether a patent transfer agreement conveys all substantial rights under a patent to a transferee or fewer than all of those rights, a court must assess the substance of the rights transferred and the intention of the parties involved." Intellectual Prop. Dev., Inc. v. TCI Cablevision of California, Inc., 248 F.3d 1333, 1342 (Fed. Cir. 2001). "In making such a determination, it is helpful to focus on each party's collection of sticks within the bundle of patent rights as a result of the agreement." IP Innovation LLC v. Google, Inc., 661 F. Supp. 2d 659, 663 (E.D. Tex. 2009) (emphasis added).

Here, [redacted] See, e.g., Frazier v. Map Oil Tools, Inc., No. CIV.A.C-10-4, 2010 WL 2352056, at *2 (S.D. Tex. June 10, 2010) ("Movant's standing to sue and thus its ability to intervene depends in large part on whether it is an exclusive or non-exclusive licensee, and more particularly whether it has the right to prevent others from using and selling the patented product.").

3

Put simply, [redacted] See, e.g., Ortho Pharm. Corp. v. Genetics Inst., Inc., 52 F.3d 1026, 1031 (Fed. Cir. 1995) (holding that licensee did not acquire required "proprietary sticks from the bundle of patent rights"). Accordingly, Apple's Motion should be denied as a matter of law. See Intel Corp. v. Broadcom Corp., 173 F. Supp. 2d 201, 220 (D. Del. 2001) ("Under Delaware law, the interpretation of a patent license agreement is a question of law.").3

2. At the Very Least, Apple's Motion Should Be Stayed Pending Discovery.

"[W]here the provisions of a contract are plain and unambiguous, 'evidence outside the

four corners of the document as to what was actually intended is generally inadmissible." Ace Capital v. Varadam Found, 392 F. Supp. 2d 671, 674 (D. Del. 2005). Here, [redacted] Assuming arguendo [redacted] then Apple's Motion should be stayed and Lodsys should be allowed to conduct discovery

concerning [redacted] For example, [redacted] But Apple failed to provide this court with [redacted]

3[redacted]

4

[redacted] Discovery concerning [redacted] See Declaration of Christopher M. Huck (the "Huck Decl."), Ex. 1 ("Patentees may also consider including a provision in the license that make validity challenges to a licensed patent a material breach allowing termination.").

Moreover, Apple has repeatedly refused to provide information relevant to its request for

intervention. For example, Apple previously refused to provide even Lodsys's counsel with a

complete copy of the License and, instead, redacted all but two paragraphs of the License.

Tellingly, the two (and only two) paragraphs that Apple disclosed did not include [redacted]

Subsequently, Apple filed the License under seal for attorneys' eyes only, so that Lodsys could

not review the actual terms of License, [redacted] Apple's disingenuous conduct

and repeated attempts to hide the ball should not be rewarded. Accordingly, if [redacted] then Apple's Motion should be stayed and Lodsys should be allowed (among other issues)[redacted]

B. Additional Threshold Matter: Apple's Motion is Premature.

"Courts should discourage premature intervention that wastes judicial resources." Sierra Club v. Espy, 18 F.3d 1202, 1206 (5th Cir. 1994). Indeed, Rule 24 "does not require the Court to permit intervention based upon speculation that intervention may be useful for protecting one's rights, if the need for such protection should arise at some point in the proceeding." United States v. Microsoft Corp., No. CIV.A.98-1232(CKK), 2002 WL 319784, *2 (D.D.C. Jan. 28, 2002); see also Ramirez v. Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Auth., 28 F. Supp. 2d 1019, 1020-21 (W.D. Tex. 1998) ("The '[rjipeness doctrine reflects the determination that courts should decide only a 'real, substantial controversy,' not mere hypothetical questions.'").

Intervention is premature where (as here) the defendants have not yet answered the complaint and, thus, the movant (and the Court) can only speculate concerning whether the

5

requirements of Rule 24 are satisfied. See Flynn v. Hubbard, 782 F.2d 1084, 1089 (1st Cir. 1986) ("It would be premature to decide now whether the interests asserted by [movants] meet the requirements of Rule 24."); see also Espy, 18 F.3d at 1206 ("A better gauge of promptness is the speed with which the would-be intervenor acted when it became aware that its interests would no longer be protected by the original parties.") (emphasis added).

Here, Apple moved to intervene only nine days after Lodsys filed its original Complaint. No defendant has answered the original Complaint or Lodsys's Amended Complaint. And there is not even the slightest hint yet that the defendants will inadequately represent Apple's purported interest. In fact, Apple trumpets the "early stage" of this proceeding:

Apple moved while the case was still in its infancy: the lawsuit was filed just over a week ago, the defendants have not yet answered Lodsys's Complaint (indeed, upon information and belief, they have not yet even been served with the summons and Complaint), and no other significant developments have taken place.

Motion at 9 (emphasis added). Apple also admits (several times) in its Motion that the defense and declaratory counterclaim raised in its Proposed Answer "will likely be raised by every defendant." Motion at 10 (emphasis added). Thus, at this "early stage" in the proceedings, Apple's assertion that its purported interests will not be protected by the defendants is pure speculation. See Shaunfieldv. Citicorp Diners Club, Inc., No. 3:04-CV-1087-G, 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 11244, *8-9 (N.D. Tex. June 8, 2005) ("Timeliness for purposes of intervention is determined from the point that the intervenor learns that its interest in the lawsuit would not be adequately protected by the other parties, not from inception of the case or the date the intervenor learned of the litigation.") (emphasis added).

Moreover, Apple repeatedly postulates that its "rights will not be adequately protected by the current defendants in this case, because Lodsys has chosen to assert these claims against Developers who are individuals or small entities with far fewer resources." Motion at 2 (emphasis added). But the premature nature of Apple's Motion is illuminated by the fact that Lodsys's Amended Complaint names as defendants several large Developers with substantial financial and technical resources, including Electronic Arts (see Huck Decl., Ex. 2 (net revenues

6

of $3,589 billion)) and Rovio. See Huck Decl., Ex. 3 (three of five "Top Paid iPad Apps"). Even assuming arguendo that Apple's characterization of the original defendants is accurate (which it is not), Apple cannot seriously dispute that the additional defendants will more than adequately represent Apple's purported interests. "Accordingly, inasmuch as [Apple] seek[s] to intervene in anticipation of an actual need for intervention, the Court shall deny the motion as premature." Microsoft, 2002 WL 319784 at *2.

C. Apple is Not Entitled to Intervention as a Matter of Right Under Rule 24(a).

A movant seeking to intervene as of right under Rule 24(a) must satisfy four requirements:

(1) the movant must timely file a motion; (2) the movant must claim an interest in the property or transaction that is the subject of the action; and (3) the movant must show that disposition of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the applicant's ability to protect that interest; and (4) the movant's interest must not be adequately represented by existing parties to the litigation

S.E.C. v. Provident Royalties, LLC, CIV. 3:09-CV-1238-L, 2010 WL 27185, *1 (N.D. Tex. Jan. 5, 2010). If the movant "fails to meet any one of those requirements then it cannot intervene as of right." Bush v. Viterna, 740 F.2d 350, 354 (5th Cir. 1984) (emphasis added). As discussed below, here Apple does not (and cannot) satisfy any of the four requirements.

1. Apple's Motion is Untimely.

"The timeliness clock does not run from the date the potential intervener knew or reasonably should have known of the existence of the case into which she seeks to intervene." John Doe No. 1 v. Glickman, 256 F.3d 371, 377 (5th Cir. 2001) (emphasis added). Rather, "[t]he timeliness clock runs either from the time the applicant knew or reasonably should have known of his interest,...or from the time he became aware that his interest would no longer be protected by the existing parties to the lawsuit." Edwards v. City of Houston, 78 F.3d 983, 1000 (5th Cir. 1996) (emphasis added).

Here, Apple's Motion is untimely because it is premature. Indeed, as discussed above, the underlying theme of Apple's Motion — i.e., that the defendants were supposedly too small and without adequate resources — has already been proved false by Lodsys's Amended

7

Complaint. No additional judicial resources should be wasted speculating about whether Apple's request for intervention may some day in the future be ripe. See Dial v. P"ship for Response & Recovery, No. 1:09-CV-218, 2010 WL 1054884, *2 (E.D. Tex. Feb. 23, 2010) ("Essentially, ripeness is 'peculiarly a question of timing.'"). Accordingly, Apple's Motion should be denied as moot or, at the very least, stayed until the defendants have answered Lodsys's Amended Complaint.

2. Apple Lacks Any Direct, Substantial and Legally Protectable Interest.

"To meet the second requirement for Rule 24(a)(2) intervention, a potential intervenor

must demonstrate that he has an interest that is related to the property or transaction that forms the basis of the controversy." James v. Harris County Sheriffs Dept., No. CIV.A. H-04-3576, 2005 WL 1878204, *2 (S.D. Tex. Aug. 9, 2005). "Not any interest, however, is sufficient; the interest must be "direct, substantial, [and] legally protectable." Saldano v. Roach, 363 F.3d 545, 551 (5th Cir. 2004) (emphasis added). "Economic interest alone is insufficient, as a legally protectable interest is required for intervention under Rule 24(a)(2)." New Orleans Pub. Serv., Inc. v. United Gas Pipe Line Co., 732 F.2d 452, 463 (5th Cir. 1984). "Further, the interest must be 'one which the substantive law recognizes as belonging to or being owned by the applicant.'" Ouch v. Sharpless, 237 F.R.D. 163, 166 (E.D. Tex. 2006).

First, Apple asserts that its "[ljicense rights" are "protectable under the law." Motion at 10. But, as discussed above, [redacted]

8

See Adams, 2011 WL 665821 at *4 ("intervention is improper where the intervenor does not itself possess the only substantive legal right it seeks to assert in the action").

Second, relying on cases involving the relationship between manufacturers and customers, Apple asserts that "Courts have consistently held that a legally sufficient interest is implicated." Motion at 11. But the authority on which Apple relies is inapposite, because the defendants (and other Developers) are not Apple's customers. In fact, based on a review of publically available information, it appears that (at Apple's insistence) Apple and the Developers expressly "acknowledge and agree that their relationship under this Schedule 1 is, and shall be, that of principal and agent, and that [Developers], as principal, are, and shall be, solely responsible for any and all claims and liabilities involving or relating to, the Licensed Applications..." Huck Decl., Ex. 4 ("iPhone Developer Program License Agreement") at Schedule 1, TJ1.3.4

And, contrary to Apple's assertions in its Motion, Apple expressly disclaims any relationship between Developers and Apple except for Developers as principals. See id. at fl54 ("Except for the agency appointment as specifically set for in Schedule 1 (if applicable), this Agreement will not be construed as creating any other agency relationship, or partnership, joint venture, fiduciary duty, or any other form of legal association between You and Apple....") (emphasis added). Thus, by Apple's design, the relationship between Apple and the Developers is the complete opposite of the manufacturer and customer relationship.

Third, Apple asserts "this litigation has fundamentally disrupted Apple's relationships with the Developers and with other developers." Motion 11. But Apple does not even attempt to qualify or quantify the alleged "disruption" and, in any event, an interest must be more concrete. See Rigco, Inc. v. Rauscher Pierce Refsnes, Inc., 110 F.R.D. 180, 183 (N.D. Tex. 1986) ("The term 'interest' is narrowly read to mean a direct and substantial interest in the proceedings.").

Fourth, Apple asserts that "[t]he potential loss of revenue, developers, or goodwill provides yet another independent basis" for intervention. Motion at 11. But "something more

4This Court may review matters of public record and documents referenced in, but not attached to, Apple's Proposed Answer. See Funk v. Stryker Corp., 631 F.3d 777, 783 (5th Cir. 2011).

9

than an economic interest is necessary." Adams, 2011 WL 665821 at *4 (emphasis added). Indeed, "courts in this circuit have found interests to be purely economic and insufficient under Rule 24(a)(2) when the party seeking to intervene fails to assert a claim for which it is the real party in interest." In re Babcock & Wilcox Co., No. CIV. A. 01-912, 2001 WL 1095031, *4 (E.D. La. Sept. 18, 2001); see also Bouchard v. Union Pac. R. Co., No. CIV.A.H-08-1156, 2009 WL 1506677, *2 (S.D. Tex. May 28, 2009) ("This requires a showing of something more than a mere economic interest; rather, the interest must be 'one which the substantive law recognizes as belonging to or being owned by the applicant.'").

Fifth, relying on Negotiated Data Solutions, LLC v. Dell, Inc., No. 2:06-cv 528 (E.D. Tex. Oct. 23, 2008), and U.S. Ethernet Innovations, LLC v. Acer, Inc. et al, No. 6:09-cv-448 (E.D. Tex. May 10, 2010), Apple asserts that, "under these exact circumstances, courts in this district have concluded that intervention as a matter of right is appropriate." Motion at 8. But Apple seriously overstates the application of both cases. For example, the motion to intervene in Negotiated Data Solutions was partially unopposed, the Order itself (Sanders Decl., Ex. D) is one paragraph and does not contain the Court's analysis, and the underlying briefing is under seal, so there is no way to glean any further information. Similarly, in U.S. Ethernet Innovations, the Court's Order (Sanders Decl., Ex. E) focused on Intel's (the proposed intervenor) indemnification obligations with the defendants as establishing a legal relationship and Intel was apparently not licensed by the plaintiff, so a finding of infringement could implicate Intel's products. Neither factor is applicable here, because Apple does not assert any indemnification obligations and Apple is licensed.5

Because Apple lacks any direct, substantial and legally protectable interest, Apple's Motion should be denied.

5Apple admits that "indemnification obligations are sometimes at issue in cases under Rule 24(a)." Tellingly, however, Apple does not discuss its lack of indemnity obligations to the Developers. Indeed, although Apple's Motion hints that it may have obligations to the Developers, the opposite is true because Apple has required the Developers to "agree to indemnify, defend and hold harmless Apple ... from any and all claims, losses, liabilities, damages, expenses and costs ... as a result of... any claims that [Developers'] Applications or the distribution, sale, offer to sale, use or importation of [Developers'] Applications (whether alone or as an essential part of a combination)... infringe any third party intellectual property or proprietary rights...." Huck Dec, Ex. 4 at 1.

10

3. Apple's Purported Interest Will Not Be Impaired Absent Intervention.

Apple asserts that, unless it is allowed to intervene, its interests will be impaired because