There are more comments filed with the FTC in response to its request for input on the proposed agreement in In the Matter of Motorola Mobility LLC, a limited liability company, and Google Inc., a corporation; FTC File No. 121 0120. As I mentioned earlier, not everyone is jumping on the currently fashionable bandwagon holding that if you donate a patent to a standards body, you give up all rights to injunctions. In fact, it's easier to find opposition than support. I showed you RIM's and CCIA's last time, two of the entities that don't think it's right to take away property rights from patent owners. And here are two more, the Washington Legal Foundation [PDF] and Qualcomm [PDF]. WLF argues that what the FTC proposes is in excess of its authority and its expertise, that it's a violation of the Noerr-Pennington doctrine and the First Amendment. Qualcomm says if the FTC makes this a template applicable to everyone else, it will result in more litigation, not less. I've done them both as text for you, and I have snippets from several more, who raise serious questions about the legality, including the Constitutionality, of what the FTC is proposing.

Jump To Comments

In case you think I've just cherry-picked the few comments that oppose the agreement, I'll show you a few more introductions, to give you the full picture. This proposed agreement is wildly unpopular.

For example, here's the introduction to the comment [PDF] from the International Center for Law & Economics, which argues that the FTC's enforcement action has no "proper grounding in antitrust law" in that there is no punishment for a monopoly legally acquired, besides which there is no evidence of consumer harm, that FRAND disputes are essentially contractual disputes, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and therefore the FTC solution will actually encourage infringement by lowering its cost:

Introduction

We appreciate this opportunity to comment on the proposed Consent Agreement and Order in this matter. The Order is aimed at imposing some limits on an area of great complexity and vigorous debate among industry, patent experts and global standards bodies: the allowable process for enforcing FRAND licensing of SEPs. The most notable aspect of the Order is its treatment of the process by which Google and, if extended, patent holders generally may attempt to enforce their FRAND-obligated SEPs through injunctions.

As an initial and highly relevant matter, it is essential to note that the FTC’s enforcement action in this case has no proper grounding in antitrust law. Under the doctrines set down in Trinko1 and NYNEX,2 among other cases,3 there is no basis for liability under Section 2 of the Sherman Act because the exercise of lawfully acquired monopoly power is not actionable under the antitrust laws. Even under Section 5 of the FTC Act the action has no basis: The Commissioners who supported the action could not agree whether its legal basis rested in unfair acts or practices or unfair methods of competition, and under an unfair methods of competition analysis (which was supported by most of the commissioners), the action is unsound because there is no evidence of consumer harm.

With respect to the terms of the Order itself, we believe that superimposing process restraints from above is not the best approach in dealing with what is, in essence, a contract dispute. Few can doubt the benefits of greater clarity in this process; the question is whether the FTC’s particular approach to the problem sacrifices too much in exchange for such clarity. FRAND terms are inherently indeterminate and flexible. Indeed, they often apply precisely in situations where licensors and licensees need flexibility because each licensing circumstance is nuanced and a one-size-fits-all approach is not workable. Enforced “certainty” by the Commission, without proper grounding in antitrust principles and doctrine, may impose costly constraints on innovation without commensurate gains.4

Instead, we believe that parties should be held to the agreements they make with SSOs, whose role is to ensure that standards are workable and that the licensing of patents that read on them is not abused. This approach has worked in the past and still functions well today. The proposed Order alters the current incentive structure, encourages infringement by lowering its costs, and creates a disincentive to standardize and to license. Where anticompetitive practices occur, as with unlawful collusion, the FTC clearly has authority to act. However, blanket constraints without antitrust grounding on a crucial method of patent enforcement will weaken the very structure the FTC is trying to strengthen.

___________

1 Verizon Commc’ns Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis v. Trinko, 540 U.S. 398, 411 (2004).

2 NYNEX Corp. v. Discon, Inc., 525 U.S. 128, 133 (1998).

3 See, e.g., Weyerhaeuser Co. v. Ross-Simmons Hardwood Lumber Co., 127 S. Ct. 1069, 1078 (2007); Brooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Co., 509 U.S. 209, 223 (1993).

4 On the problem of error costs in antitrust, particularly in innovative markets, see Geoffrey A. Manne & Joshua D. Wright, Innovation and the Limits of Antitrust, 6 J. COMPETITION L. & ECON. 153 (2010). See also Frank H. Easterbrook, The Limits of Antitrust, 63 TEX. L. REV. 1 (1984).

By the way, Apple even says in its comment [PDF]: "SEP holders should not seek injunctions when they have made a FRAND commitment absent exceptional circumstances." So Apple is not seeking a total ban on injunctions. And who defines "exceptional circumstances"? How about when Apple

told the judge in Wisconsin that they'd only obey her order setting a FRAND rate for Apple if Apple thought it was low enough? Would that be an "exceptional circumstance" that would allow the other side to seek an injunction? After all, is that your definition of a "willing" licensee, one that sets a price itself while denying the patent holder the right to even negotiate and dictates to judges what the price should be?

And here's a taste of Ericsson's comment [PDF]:

Ericsson has extensive experience with standard essential patents ("SEPs") in the telecommunications industry as a member of standard setting organizations and as both a licensee and a licensor of SEPs. Based on this experience, Ericsson believes that the Google template may adversely affect the standard setting process and may inhibit innovation. Ericsson is also concerned that the assumptions about potential competitive harm underlying the Google template may not be supported by actual industry experience. From Ericsson's perspective, the existing standard setting process in the telecommunications industry, which contemplates the availability of injunctive relief, has encouraged the development of an extremely competitive and innovative industry.

Ericsson therefore urges the Commission to limit the Order to the unique circumstances of this case and to refrain from identifying the resolution as a template with broader applicability. Ericsson also requests that the Commission conduct further empirical investigation and analysis based on input from standard-setting organizations, and industry participants before reaching any further conclusion regarding the appropriate use of injunctive relief with respect to standard essential patents.

Although Ericsson agrees with the Commission that, in general, injunctive relief should be available against an unwilling licensee who refuses to accept a license on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory ("FRAND") terms, Ericsson believes that the specific procedures described in the Order, if widely adopted, may cause unintended and undesirable consequences, particularly within the telecommunications industry. For example, unnecessary restrictions on the availability of injunctive relief against unwilling licensees may discourage companies such as Ericsson from contributing to open standards, with their demonstrated benefits of improving consumer choice, lowering prices, and encouraging ongoing innovation.

Due to these concerns, Ericsson advocates a more deliberate and consensus-oriented approach to any changes to FRAND licensing practices within the telecommunications industry and beyond. Ericsson believes that the facts of this case should not be extrapolated into wider policy guidance by the Commission on how FRAND licensing should be done. Rather, any changes to FRAND policies should involve industry wide consultation with key stakeholders both implementers of and contributors to the standards-in order to ensure that the right balance between open access to the standards and proper incentives to contribute to the standards is reached.

Here's part of the comment from the Innovation Alliance [PDF], which points out that in the US, the Constitution permits citizens to seek redress of grievances from the government, and that means access to the courts ("Because of the First Amendment rights involved, not even Congress may enact laws that punish or prohibit good faith efforts to petition a court for injunctive or other relief by any citizen, including FRAND-encumbered patent holders>":

The Proposed Order threatens to challenge SEP-holders' attempts to enjoin infringement by "willing licensees" as stand-alone violations of Section 5 of the FTC Act. As explained fully below, the Commission's sweeping declaration would unlawfully interfere with rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution and would otherwise represent an impermissible expansion of the Commission's authority under Section 5. Indeed, the Proposed Order would permit the Commission to usurp the role of the courts and the International Trade Commission (the "ITC"). Moreover, the context of this matter-a consent decree concerning a proposed merger independently raises serious concerns about using the Proposed Order to declare that requests to enjoin infringement of FRAND-encumbered patents violate Section 5. It would be imprudent at best for the Commission to adopt such a sweeping rule in the context of a matter that, at most, only tangentially implicates the issue and in which the Commission knows the parties have no serious incentive to oppose the rule.

I. The Proposed Order Would Unlawfully Impinge on Patent Holders' First

Amendment Right to Petition The Government.

A. SEP-Holders, Like All Citizens, Have the Right to Petition Courts in Good

Faith for Relief.

The First Amendment guarantees all citizens the right "to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." U.S. CONST. amend I. That fundamental right is "among the most precious ofthe liberties safeguarded by the Bill of Rights." United Mine Workers of Am., Dist. 12 v. Ill. State Bar Ass 'n, 389 U.S. 217, 222 (1967); accord Hollister v. Soetoro, 258 F.R.D. 1, 1 (D.D.C. 2009) ("Our liberties are manifold and are the envy ofthe world. In the very top tier of those liberties, enshrined in the First Amendment, is 'the right of the people . . . to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."'). The right to petition includes " [t]he right of access to the courts." Ca. Motor. Transp. Co. v. Trucking Unlimited, 404 U.S. 508, 510 (1972). For this reason, under what is commonly known as the Noerr-Pennington doctrine, the Supreme Court has unequivocally declared that good faith efforts to seek relief from courts cannot give rise to liability under antitrust or other laws, regardless of any anticompetitive impacts that may flow from the litigation or requested relief. Prof'l Real Estate Investors, Inc. v. Columbia Pictures Indus., Inc., 508 U.S. 49, 56 (1993) ("Those who petition government for redress are generally immune from antitrust liability."); City of Columbia v. Omni Outdoor Adver., Inc., 499 U.S. 365, 381 (1991) ("If Noerr teaches anything it is that an intent to restrain trade as a result of the government action sought ... does not foreclose protection."); id. at 379-80 ("The federal antitrust laws . .. do not regulate the conduct of private individuals in seeking anticompetitive action from the government.").

Holders of FRAND-encumbered patents are entitled to exercise their fundamental right to petition the courts and government agencies to the same extent as other citizens. See, e.g, Apple, Inc. v. Motorola Mobility, Inc.,--- F. Supp. 2d ---, 2012 WL 3289835, at *11 (W.D. Wis. Aug.

10, 2012); see also ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH v. Canaday Tech. LLC, 629 F.3d 1279, 1291-92 (Fed. Cir. 2010). The District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin recently recognized this basic constitutional principle in Apple v. Motorola by rejecting Apple's argument that antitrust principles precluded Motorola from seeking injunctive relief related to FRAND-encumbered patents. See Apple, 2012 WL 3289835, at* 14. Indeed, the court made clear that Motorola's request for injunctive relief was "immune under the Noerr-Pennington doctrine." Id.

Because of the First Amendment rights involved, not even Congress may enact laws that punish or prohibit good faith efforts to petition a court for injunctive or other relief by any citizen, including FRAND-encumbered patent holders.

As you can see, the FTC proposed agreement isn't popular at all, and many are expressing deep and abiding concerns about fundamental legal and Constitutional principles being undermined by any rule that FRAND patent holders have no right to seek injunctions. Companies that are familiar with standards bodies and SEPs are telling the FTC that it's gone too far and that there will be unintended consequences that nobody will like. Well, Apple and Microsoft maybe will like it. This is their party. And if you were around and watching Microsoft's behavior getting its OOXML approved as a so-called standard, you know what it is capable of. But if their proposed legal theory about FRAND patents violates the First Amendment, the

Noerr-Pennington doctrine, anti-trust law, etc., not to mention simple fairness, what are they smoking? No. What would *we* need to be smoking to go along with it?

Here's the Washington Legal Foundation's comment [PDF] in full, as text:

File

No. 121-0120

__________________

COMMENTS

of

THE WASHINGTON LEGAL FOUNDATION

to the

FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION

Concerning

IN THE MATTER OF

MOTOROLA MOBILITY LLC and GOOGLE INC.;

REQUESTS FOR

COMMENTS ON

PROPOSED CONSENT AGREEMENT

Richard A. Samp

Cory L. Andrews

Washington

Legal Foundation

[address, phone]

February 22, 2013

[Washington Legal Foundation letterhead]

February 22, 2013

Submitted Electronically

Federal Trade Commission

Office of the Secretary

[address]

Washington, DC 20580

Re: In the Matter of Motorola Mobility LLC and Google Inc.;

Request for

Comments on Proposed Consent Agreement

File No. 121-0120; 78 Fed. Reg. 2398 (January

11, 2013)

Dear Commissioners:

The Washington Legal Foundation (WLF) appreciates this

opportunity to submit these comments to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in

connection with the FTC’s proposed Consent Agreement with Motorola Mobility, LLC and

Google Inc. WLF is a non-profit public interest law and policy center based in

Washington, D.C. with supporters nationwide. WLF promotes free-market policies

through litigation, administrative proceedings, publications, and advocacy before

state and federal government agencies, including the FTC.

The proposed Consent

Agreement arises in connection with litigation initiated by Motorola (and continued

by Google following Google’s June 2012 purchase of Motorola) in which Motorola sought

injunctions and exclusion orders against competitors who allegedly were infringing

patents held by Motorola. The patents in question have been designated as standard

essential patents (SEPs) for cellular, video codec, and wireless LAN standards. The

FTC’s Complaint alleges that Motorola and Google, by seeking injunctive relief and

exclusion orders, engaged in unfair methods of competition and unfair acts or

practices, in violation of Section 5

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page

2

of the Federal Trade Commission Act, 15 U.S.C. § 45. Under the proposed Agreement,

Motorola and Google do not admit that they violated the FTC Act, but they have agreed

to a Consent Order that would significantly restrict the forms of relief they are

entitled to seek in patent infringement proceedings.

WLF expresses no views regarding

factual allegations contained in the FTC’s Complaint. WLF lacks any detailed

knowledge regarding patent infringement litigation initiated by Motorola and thus is

not in a position to take issue with the FTC’s factual allegations. Moreover, WLF

sees no basis for challenging the wisdom of the patent dispute resolution procedures

set forth in the Consent Order. Those procedures appear reasonably well designed to

reduce the level of patent litigation by encouraging parties to settle their

disagreements regarding the appropriate size of patent royalties.

But WLF strenuously

objects to the FTC’s exercise of its Section 5 authority with total disregard for the

Noerr-Pennington doctrine, a Supreme Court doctrine designed to protect the First

Amendment rights of businesses (including monopolists) to petition the government for

relief without regard to whether the requested relief would restrain trade. The

conduct alleged here (seeking injunctive relief in court proceedings and seeking

exclusion orders in proceedings before the International Trade Commission) fits

squarely within the four corners of the Noerr- Pennington doctrine. Accordingly, the

conduct is not subject to sanction under Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act, 15

U.S.C. §§ 1 & 2. The Statements of the various Commissioners do not explicitly set

forth their views on whether the Commission’s Section 5 authority is similarly

constrained by the Noerr-Pennington doctrine. The answer to that question is

reasonably clear:

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 3

the doctrine

does, indeed, limit the reach of Section 5 because it is based on principles set

forth in the First Amendment, a constitutional provision that is binding on the

Commission.

Several Commissioners suggest that Motorola and Google may have waived

their First Amendment rights. Yet they fail to point to any evidence to support that

claim. The contractual commitments made by Motorola to standard-setting organizations

(SSOs) are silent regarding the relief that may be sought in patent infringement

litigation; more importantly, they say absolutely nothing about the First Amendment.

Case law is clear that constitutional rights are not deemed waived unless the alleged

waiver is set forth explicitly. Motorola and Google promised to offer licenses for

their SEPs on FRAND (“fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory”) terms, but that

promise says nothing about the nature of litigation they would initiate against

companies that practice the SEPS without a license. The FTC alleges that they failed

to offer licenses on FRAND terms to several willing licensees; if so, they breached a

contractual commitment. But any such breach is separate and apart from the efforts of

Motorola and Google to petition the federal courts, efforts that are protected by the

First Amendment.

If, as the FTC believes, the FRAND commitment bars Motorola and

Google from obtaining injunctive relief against alleged infringers, then one can

expect federal courts and the International Trade Commission to arrive at the same

conclusion after reviewing the same contractual material. Indeed, the evidence

indicates that federal courts are quite reluctant to grant injunctive relief to SEP

holders that have made FRAND commitments. Accordingly, there is little reason for the

FTC to run roughshod over First Amendment rights in order to achieve a result that

almost surely would have been achieved in any event. Moreover, the danger

Federal

Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 4

(perceived by the FTC) that an injunction

demand might cause defendants to sign settlement agreements calling for unreasonably

high royalties (and then pass those costs on to consumers) becomes a factor of

diminishing importance as their awareness increases that courts are highly unlikely

to grant requested injunctive relief.

I. Interests of the Washington Legal

Foundation

The Washington Legal Foundation is a public interest law and policy center

based in Washington, D.C., with members and supporters in all 50 States. WLF

devotes a substantial portion of its resources to defending free enterprise,

individual rights, and a limited and accountable government. To that end, WLF

regularly appears before federal and State courts and administrative agencies to

promote economic liberty, free enterprise, and a limited and accountable government.

WLF has frequently appeared as amicus curiae in the federal courts to address the

proper scope of the antitrust laws. See, e.g., Pacific Bell Tel. Co. v. linkLine

Communications, Inc., 555 U.S. 438 (2009); Weyerhaeuser Co. v. Ross-Simmons Hardware

Lumber Co., 549 U.S. 312 (2007); Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 127 (2007).

In particular, WLF filed briefs in several of the principal federal court cases that

have addressed the antitrust implications of patent litigation settlements under

which the defendant agrees to delay plans to market a generic version of a

prescription drug. See, e.g., In re K-Dur Antitrust Litigation, 686 F.3d 197 (3d Cir.

2012), petitions for cert. pending, Nos. 12-245 & 12-265 (filed Aug. 2012);

Schering-Plough Corp. v. FTC, 402 F.3d 1056 (11th Cir. 2005), cert denied, 548 U.S.

919 (2006); Valley Drug Co. v. Geneva Pharms., Inc., 344 F.3d 1294 (11th Cir. 2003).

WLF is scheduled to file a merits brief in the U.S. Supreme Court next week on that

same issue,

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 5

in FTC v. Actavis, No.

12-416. WLF also filed a brief with the FTC in Schering-Plough when that case was

before the Commission.

WLF is filing these comments due to its interest in promoting

patent rights, including the rights of patentees to petition the federal courts in an

effort to protect their patents. WLF has no direct interest in this matter and has

not discussed its comments with any of the parties. WLF takes no position regarding

any of the factual allegations in either the Complaint or the Statement of the

Commission, other than the allegation that Motorola and Google took actions that

constituted a waiver of their First Amendment rights.

II. FTC’s Statutory

Authority

Federal law authorizes the FTC to prevent businesses and individuals (with

certain limited exceptions) from “using unfair methods of competition in or affecting

commerce and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce.” 15

U.S.C. § 45(a)(2). The FTC “shall have no authority” to declare an act or practice

unfair unless it is “likely to cause substantial injury to consumers,” and the injury

“is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and not outweighed by

countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.” 15 U.S.C. § 45(n). It is

empowered to issue cease-and-desist orders, ordering individuals and entities not to

engage in acts or practices it determines to be in violation of the FTC Act. 15

U.S.C. § 45(b).

As an agency of the United States, the FTC is subject to limitations

imposed by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which explicitly protects

the right of the people “to petition the Government for a redress of

grievances.”

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 6

III. The Sherman

Act and the Noerr-Pennington Doctrine

The Sherman Act prohibits contracts,

combinations, or conspiracies “in restraint of trade,” 15 U.S.C. § 1, and

monopolizing or attempting to monopolize “any part of the trade or commerce among the

several States.” 15 U.S.C. § 2. In a series of cases dating back more than half a

century, the Supreme Court has made clear, however, that the Sherman Act does not

restrict the rights of people to associate together to persuade the government to

adopt new laws, even if the laws would have the effect of restraining trade or

promoting a monopoly. See, Eastern Railroad Presidents Conference v. Noerr Motor

Freight, Inc., 365 U.S. 127 (1961); Mine Workers v. Pennington, 381 U.S. 657 (1965).

The petitioners’ motivation in urging government action is deemed irrelevant;

“[j]oint efforts to influence public officials do not violate the antitrust laws even

though intended to eliminate competition.” Id. at 670. The law established by those

cases is generally referred to as the Noerr-Pennington doctrine.

The Court reasoned

that in light of the Government’s “power to act in [its] representative capacity,”

and “to take actions . . . that operate to restrain trade,” the Sherman Act should

not be deemed to punish “political activity” through which “the people . . . freely

inform the government of their wishes.” Noerr, 365 U.S. at 529. Noting that the First

Amendment protects the right of the people to petition the Government, the Court said

that it would not “impute to Congress an intent to invade” First Amendment rights

when adopting the Sherman Act. Id. at 530. Although Noerr and Pennington involved

petitions submitted to legislative and administrative bodies, the Court later

clarified that the Noerr-Pennington doctrine also applies to the filing of lawsuits.

California Motor Transport Co. v. Trucking Unlimited, 404 U.S. 508

Federal Trade

Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 7

(1972). The Court has repeatedly made clear that

the doctrine is firmly grounded in First Amendment doctrine: “[I]t is obviously

peculiar in a democracy, and perhaps in derogation of the constitutional right ‘to

petition the Government for a redress of grievances,’ U.S. Const., Amdt. 1, to

establish a category of lawful state action that citizens are not permitted to urge.”

City of Columbia v. Omni Outdoor Advertising, Inc., 499 U.S. 365, 379 (1991). See

also Prof. Real Estate Investors, Inc. v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc., 508

U.S. 49, 56 (1993).

IV. The Noerr-Pennington Doctrine Is Fully Applicable to the

FTC

The Statement of the Commission in this matter does not state explicitly whether

the Commission deems the Noerr-Pennington doctrine to be applicable to FTC

proceedings. It is true, of course, that the Noerr-Pennington doctrine arose in the

context of litigation under the Sherman Act, not under Section 5 of the FTC Act. WLF

recognizes that the Commission on occasion takes the position that its Section 5

antitrust enforcement powers extend beyond the confines of the Sherman Act. Case law

is nonetheless reasonably clear that the Noerr- Pennington doctrine is fully

applicable to Section 5 proceedings and constrains the Commission’s authority to

sanction companies based on the lawsuits they file.

Although the Supreme Court has

usually discussed the Noerr-Pennington doctrine in the context of Sherman Act claims,

in none of those cases did the Court indicate that its analysis was unique to the

Sherman Act context and inapplicable to other antitrust claims. See, e.g.,

Pennington, 381 U.S. at 370 (stating that “[j]oint efforts to influence public

officials do not violate the antitrust laws even though intended to eliminate

competition”) (emphasis added). In at least once instance, the Court discussed the

doctrine’s applicability in the context of an FTC

Federal Trade Commission

February

22, 2013

Page 8

lawsuit filed under Section 5 of the FTC Act. See, FTC v. Superior

Court Trial Lawyers Ass’n, 483 U.S. 411 (1990). Although the Court concluded in that

case that the defendants’ allegedly unfair acts or practices were not immunized from

antitrust scrutiny by Noerr-Pennington, it gave no indication that it deemed the

doctrine inapplicable to Section 5 claims. Id. at 424-25.

More importantly, the

doctrine’s First Amendment foundation is powerful evidence that the FTC is not

entitled to exempt itself from the doctrine. As explained above, the Supreme Court

recognized the doctrine in light of the First Amendment’s grant of a right to

petition the government “for a redress of grievances.” Filing Section 5 enforcement

actions against companies because they file non-sham federal court lawsuits would

interfere with the right to petition for a redress of grievances just as assuredly as

actions filed under the Sherman Act. Although Congress delegated broad enforcement

powers to the Commission when it adopted the FTC Act, the Supreme Court has been

loathe to “impute to Congress an intent to invade the First Amendment right to

petition” when adopting the antitrust laws. Professional Real Estate Investors, 508

U.S. at 1926. As an arm of the federal government, the FTC is fully bound by First

Amendment restrictions; accordingly, it has no authority to exempt itself from those

restrictions by deeming the Noerr-Pennington doctrine inapplicable to Section 5

enforcement actions.

V. Motorola and Google Have Not Waived Their First Amendment

Rights

Commissioner Maureen K. Ohlhausen dissented from the FTC’s action in this

matter, in part “because the Noerr-Pennington doctrine precludes Section 5 liability

for conduct grounded in the legitimate pursuit of an injunction or any threats

incidental to it.” Dissenting Statement of

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 9

Commissioner Maureen K. Ohlhausen at 1. In response, the Commission stated:

We

are not persuaded by Commissioner Ohlhausen’s argument that the conduct alleged in

the Commission’s complaint implicates the First Amendment and the Noerr-Pennington

doctrine. As noted above, we have reason to believe that [Motorola] willingly gave up

its right to seek an injunction when it made the FRAND commitments at issue in this

case. We do not believe that imposing Section 5 liability where a SEP holder violates

its FRAND commitment offends the First Amendment because doing so in such

circumstances “simply requires those making promises to keep them.”

Statement of the

Federal Trade Commission, In the Matter of Google, Inc. (Jan. 3, 2013) at 4-5

(quoting Cohen v. Cowles Media Co., 501 U.S. 663, 670-71 (1991).1

WLF notes that the

Commission is hedging its bets here; it does not commit itself to an assertion that

Motorola and Google waived their rights to seek injunctive relief, only that “we have

reason to believe” that a waiver took place. WLF can understand the Commission’s

desire to use equivocating language, because there is not a shred of evidence that

any rights were waived, and the Commission has pointed to none. The Commission states

that Motorola and Google promised to offer licenses on FRAND terms to willing

licensees. It asserts that they breached that contractual commitment by failing to

offer licenses on FRAND terms to Apple and Microsoft, whom the FTC asserts were

willing licensees. WLF is not fully familiar with the record and thus takes no

position regarding those assertions. But a promise to offer licenses on FRAND terms

is not the issue. Rather, the issue is whether Motorola or Google ever promised not

to seek injunctive relief. The FTC has produced no evidence of such a promise.

Indeed, the

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 10

Consent

Agreement acknowledges that there exist certain circumstances under which it would be

appropriate for Motorola and Google to seek injunctive relief against alleged

infringers of its SEPs, so even the FTC acknowledges that they made no contractual

commitment never to seek injunctive relief.

The Commission apparently takes the

position that one can infer that Motorola and Google waived their litigation rights

from the fact of their FRAND commitment. Any such inference cuts against well

established principals of constitutional law. As noted above, the First Amendment

protects the right to petition the government for redress of grievances, including

the right to file non-sham litigation. The Supreme Court has held repeatedly that

constitutional rights are not deemed waived unless the alleged waiver is set forth

explicitly. See, e.g., College Savings Bk. v. Florida Prepaid Postsecondary Educ.

Expense Bd., 527 U.S. 666, 682 (1999) (“Courts indulge every reasonable presumption

against waiver of fundamental constitutional rights”); Carnley v. Cochran, 369 U.S.

506, 514 (1962); Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458, 464 (1938). In the absence of any

language in Motorola’s contractual undertakings that references the First Amendment,

or even that references the right to seek injunctive relief, any suggestion that

Motorola and Google knowingly waived their constitutional rights to petition the

government borders on the frivolous.

Of course, the fact that Motorola and Google

have a constitutional right to seek injunctive relief says nothing about whether they

are entitled to obtain such relief. The Supreme Court has made clear that injunctive

relief is never granted as a matter of course to prevailing plaintiffs in patent

infringement litigation. Instead, the Court has held that normal rules of equity

practice

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 11

apply “with equal force”

to patent infringement lawsuits and that the prevailing plaintiffs in such suits must

satisfy the rigorous “four-factor test before a court may grant [injunctive] relief.”

eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 391 (2006). The facts underlying the

patent infringement litigation filed by Motorola – in particular, its agreement to

license its SEPs on FRAND terms – might well cause a court to conclude that Motorola

could not meet the four- factor test and thus is not entitled to injunctive relief.

After all, a company that makes a FRAND commitment might well have difficulty

demonstrating that an award of damages (in the form of a retroactive licensing fee)

could not adequately compensate it for its injuries (one of the showings required

under the four-factor test). But a finding that Motorola and Google are not entitled

to injunctive relief is a far cry from a finding that they have waived their

constitutional rights to petition the courts for such relief.

None of the cases cited

by the Commission support its position. Its citation to Cohen v. Cowles Media Co. is

particularly inapt. That decision had nothing to do with waiver of constitutional

rights. It held merely that newspapers are subject to generally applicable contract

laws and could be sued for damages arising for breach of a contract. Cohen, 501 U.S.

at 670-71. Similarly, if Motorola or Google breached a contract by filing an

infringement lawsuit seeking injunctive relief, they too are subject to a suit for

damages incurred by any intended beneficiary of the contract. But that issue is

irrelevant to the issue here: whether they have knowingly waived their

Noerr-Pennington immunity from antitrust claims arising from their exercise of their

First Amendment petitioning rights.

Similarly unavailing are the two decisions cited

in Footnote 7 of the Statement of the

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page

12

Commission. Microsoft Corp. v. Motorola, Inc., 696 F.3d 872 (9th Cir. 2012),

involved a lawsuit filed by Microsoft for the purpose of preventing enforcement of a

German court’s injunction that barred Microsoft from using one of Motorola’s SEPs.

The suit made no claim that Motorola had waived any constitutional rights; rather, it

asserted merely that the RAND commitment that Motorola had made to an SSO precluded

it from obtaining injunctive relief. The Ninth Circuit did not discuss waiver of

constitutional rights, and did not even decide whether the German injunction against

Microsoft was unwarranted. Rather, it merely affirmed the district court’s grant of a

preliminary injunction against enforcement of the German injunction, based in part on

the following rationale:

We conclude that the district court did not abuse its

discretion in determining that Microsoft’s contract based claims, including its claim

that the RAND commitment precludes injunctive relief, would, if decided in favor of

Microsoft, determine the propriety of the enforcement by Motorola of the injunctive

relief obtained in Germany.

696 F.3d at 885. The Ninth Circuit could not have been

clearer that it viewed the issue as one that turned on whether Motorola could

establish the prerequisites for obtaining a permanent injunction against the use of

its SEPs, not whether it had waived its constitutional rights.2

The other cited

decision – Apple, Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., 869 F. Supp. 2d 901 (N.D. Ill. 2012)

(Posner, J., sitting by designation) – cuts strongly against the Commission’s

position. In

Federal Trade Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 13

that decision, Judge Posner dismissed the claims for

injunctive relief filed against one another by Apple and Motorola in connection with

their long-running patent disputes. In dismissing Motorola’s claims for injunctive

relief with respect to its SEPs, Judge Posner’s analysis mirrored precisely the

analysis described above by WLF, not the waiver-of-rights analysis espoused by the

Commission. Id. at 913-15. The language cited by the Commission (at Footnote 7 of its

Statement) makes our point precisely. According to Judge Posner, what is “implicit”

in Motorola’s FRAND commitment is an “acknowledg[ment] that a royalty is adequate

compensation for a license to use that patent,” 869 F. Supp. 2d at 914, not (as the

Commission would have it) a waiver of the constitutional right to petition the

government.3

In sum, there is no evidentiary support for the Commission’s assertion

that Motorola and Google have waived their First Amendment rights to petition the

government to enjoin other companies from using their SEPs. In the absence of a

waiver, the Commission is acting in excess of its Section 5 powers in bringing an

enforcement action based on the decisions of

Federal Trade Commission

February 22,

2013

Page 14

Motorola and Google to pursue injunctive relief claims in the federal

courts. Accordingly, WLF urges the FTC to withdraw its Complaint and not to enter

into the proposed Consent Agreement.

WLF nonetheless agrees with the FTC that there

has been far too much litigation over the licensing of SEPs, and that such litigation

could adversely affect competition. Accordingly, WLF has no objection to FTC efforts

to propose standard procedures for resolving licensing disputes. The mandatory

arbitration procedures set forth in the Consent Agreement strike WLF as a step in the

right direction. Perhaps the FTC can work with SSOs to encourage them, before

designating any SEPs, to require the SEP holders to commit to such procedures.

VI. The Relief Ordered by the Commission Is Particularly Inappropriate Because the

Problems Identified by the Commission Appear to Be Self-Correcting

If, as the FTC

believes, the FRAND commitment bars Motorola and Google from obtaining injunctive

relief against alleged infringers, then one can expect federal courts and the

International Trade Commission to arrive at the same conclusion after reviewing the

same contractual material. Indeed, the evidence indicates that federal courts are

quite reluctant to grant injunctive relief to SEP holders that have made FRAND

commitments.

Perhaps the best example is Judge Posner’s decision, cited above, from

June 2012. Apple Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., 869 F. Supp. 2d 901 (N.D. Ill. 2012). Judge

Posner explained at length why SEP holders are unlikely to be able to establish the

irreparable harm necessary to obtain injunctive relief. Id. at 913-915. An increasing

awareness among defendants that courts are highly unlikely to grant injunctive relief

will make them increasingly less likely to sign settlement agreements calling fo

unreasonably high royalties. It is the FTC’s fear of such “hold-

Federal Trade

Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 15

up” settlements (which may result in

unreasonably high prices being passed along to consumers) that the FTC has cited in

support of its recent intervention into SEP patent litigation. But the FTC to date

has cited no evidence of any actual consumer injury. Moreover, now that defendants’

fears of injunctions has diminished considerably, the likelihood of future consumer

injury is rapidly diminishing.

In WLF’s view, the real problem is that the value of

SEP licenses has been notoriously difficult to quantify. Not surprisingly, SEP

holders tend to believe that their patents are extremely value (separate and apart

from the increased value caused by the patents being designated as the industry

standards by SSOs), while competitors who have few realistic alternatives to

continuing to use the patents tend to have quite different appraisals of the patents’

value. The wide divergence of opinion regarding what constitutes a reasonable SEP

royalty has inevitably led to very high levels of litigation.

By bringing enforcement

actions against SEP holders, the FTC appears to be taking the side of defendants in

these royalty lawsuits. WLF questions whether that is an appropriate position for the

FTC to be taking. Making patent enforcement more difficult for SEP holders will

likely lead to a decrease in royalty payments and may even lead to a decrease in

consumer prices. But it should not be the role of the FTC to fight against

enforcement of patent rights. The patent system was adopted for the purpose of

encouraging increased research and development expenditures – in the hope that such

expenditures will lead to the development of new and useful products. WLF

respectfully suggests that the FTC lacks the technical expertise to know when royalty

being demanded by SEP holders are unreasonable and when it is the users

Federal Trade

Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 16

of the SEPs who are being unreasonable in

refusing royalty demands.

WLF encourages the FTC to devote its energies in this area

to finding ways to encourage low-cost methods of settling royalty disputes. All can

agree that the current high level of litigation creates inefficiencies. WLF applauds

the FTC’s encouragement of mandatory arbitration regimes. WLF also applauds the FTC’s

conclusion that if a user seeks a determination of a fair royalty, it must provide

the SEP holder with a commitment to abide by the court’s (or arbitrator’s)

determination regarding what constitutes a fair royalty.

Finally, WLF urges the FTC

to trust the ability of courts and the International Trade Commission to reach

appropriate resolution of SEP royalty disputes. They too have been assigned a role in

resolving such disputes. WLF deems it inappropriate for the FTC to issue decisions

whose effect is to make it the sole arbiter of those disputes.

Federal Trade

Commission

February 22, 2013

Page 17

CONCLUSION

WLF respectfully requests that the

FTC withdraw its complaint and not enter into the proposed Consent Agreement. It

further requests that the Commission: (1) explicitly acknowledge that its Section 5

enforcement authority is subject to the Noerr-Pennington doctrine; and (2) announce

that it will not take enforcement action against a SEP holder for petitioning the

courts for injunctive relief, in the absence of evidence that the SEP holder has

explicitly waived its constitutional rights to engage in such activity.

Sincerely,

/s/ Richard A. Samp

Richard A. Samp

Chief Counsel

/s/ Cory L. Andrews

Cory L. Andrews

Senior Litigation Counsel

___________

1 The Commission’s phrase, “[a]s noted above,” apparently refers to

Footnote 7 of its Statement. The footnote states, “A number of courts have recognized

the tension between Google’s FRAND commitments and seeking injunctive relief.”

Statement at 2 n.7.

2 The Ninth Circuit confined to a single sentence (the one cited in

the Commission’s Statement) any discussion of whether Motorola might have made a

contractual commitment not to seek injunctive relief. In that sentence, the court

raised the possibility (without deciding) that such a commitment could “arguably” be

“implicit” in Motorola’s RAND commitment to the SSO. 696 F.3d at 884. Other than that

passing observation, the court focused solely on the appropriateness of injunctive

relief, not on the appropriateness of seeking such relief.

3 Judge Posner relied on Motorola’s

acknowledgment of the adequacy of a royalty (as compensation for its injuries) as the

basis for dismissing Motorola’s claim for injunctive relief. He explained: [T]he

Supreme Court has held that the standard for deciding whether to grant [injunctive]

relief in patent cases is the normal equity standard. And that means, with immaterial

exceptions, that the alternative of monetary relief must be inadequate. A FRAND

royalty would provide all the relief to which Motorola would be entitled if its

proved infringement of the ’898 patent, and thus it is not entitled to an injunction.

Id. 915 (citations omitted). At no point did Judge Posner suggest that Motorola had

made a contractual commitment not to seek injunctive relief in lawsuits for

infringement of its SEPs, let alone a commitment to waive its constitutional rights

to petition the government for such relief.

And here's Qualcomm's comment [PDF] in full:

UNITED STATES FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION

WASHINGTON, D.C.

In the Matter

of

Motorola Mobility LLC and Google Inc.

File No. 121-0120

QUALCOMM INC.’S RESPONSE TO THE COMMISSION’S REQUEST FOR

COMMENTS ON THE PROPOSED

AGREEMENT CONTAINING CONSENT ORDER

(78 Fed. Reg.

2398 (Jan. 11, 2013))

___________________________

Roger G. Brooks

CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LLP

[address, phone]

Counsel for Qualcomm

Inc.

Dated: February 22, 2013

QUALCOMM Incorporated (“Qualcomm”) respectfully submits these comments in

response to the request of the Federal Trade Commission (“Commission”) for public

comment on the January 3, 2013 Decision and Order (“D&O”) issued in the

above-captioned proceeding. Qualcomm understands that the D&O is a result of

allegations and discussions particular to, and the consent of, the Respondent.

Qualcomm nonetheless is concerned that the D&O gives insufficient weight to the fact

that an injunction for infringement of a standards-essential patent (“SEP”) will not

be entered by a U.S. court unless and until any “failure to offer FRAND terms”

defense has been adjudicated against the infringer, and instead imposes a lengthy and

detailed procedure before injunctive relief can be sought. Qualcomm respectfully

suggests that certain aspects of the D&O would, if non-consensual and applied more

broadly than in this matter, result in more litigation rather than less, by

undermining the incentives of infringers to negotiate and enter into license

agreements for SEPs on FRAND terms.

I. STATEMENT OF INTEREST

Qualcomm is one of

the world’s leading communications technology development and licensing companies.

Understanding that research and development (“R&D”) is the lifeblood of innovation,

Qualcomm invests enormous amounts in developing a variety of new, enabling

technologies, in particular cellular communications and other advanced communications

technologies: $3 billion in 2011, rising from $2.5 billion the year before. Qualcomm

also holds a significant patent portfolio covering its inventions, containing over

33,000 patents, which it has licensed to more than 200 licensees, and Qualcomm has

over 77,000 patent applications pending worldwide. In addition, Qualcomm is a leading

supplier of chipsets for wireless devices. Qualcomm also licenses intellectual

property from third parties in connection with its chipset and other businesses.

Because industry standards play an important role for cellular devices and

infrastructure equipment, as well as for other communications

products, Qualcomm is

an active and longstanding participant in numerous standards-setting organizations

(“SSOs”), including the European Telecommunication Standards Institute (“ETSI”), the

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (“IEEE”), the Telecommunications

Industry Association (“TIA”), the Alliance for Telecommunications Industry Solutions

(“ATIS”), and others. Qualcomm has actively participated over the years in multiple

deliberations within these and other SSOs concerning policies regarding FRAND

commitments and licensing of SEPs.

Qualcomm’s business model situates it at the

intersection of the licensor/implementer tension. Because Qualcomm is both a

technology licensor and a supplier of chipsets for incorporation into equipment that

implements standardized technologies, Qualcomm’s business success depends both on

access to others’ patents and on the ability to monetize its patented inventions and,

if necessary, to enforce its own patents covering those inventions—including SEPs and

other, non-standards-essential patents.

Qualcomm is therefore particularly well

placed to comment on the Commission’s contemplated enforcement actions, and their

impact on SSOs, patentees, and implementers. Qualcomm appreciates the Commission’s

consideration of these comments.

II. IMPOSING REQUIREMENTS FOR SEEKING INJUNCTIVE

RELIEF IS

UNNECESSARY

The D&O provides that “Respondents shall not file a claim

seeking, or otherwise obtain or enforce” injunctive relief without first following

lengthy and detailed procedures.1

3

Elsewhere the Commission

states its concern that “seeking” injunctions may “impair competition”.2

We believe

that the Commission is correct, as a matter of contract interpretation and the law of

estoppel, that where an infringer asserts, in good faith, a defense based on an

SEP-holder’s alleged failure to offer FRAND terms to an infringer, no injunction

against the infringer should be entered and enforced unless and until that FRAND

defense has been adjudicated.

We are unclear, however, as to the nature of the

Commission’s concern regarding “seeking” injunctions (or equivalents, such as an

exclusion order) apart from actual entry and enforcement. On the one hand, the

Commission rightly does not rule out injunctions based on SEPs in all contexts; it

appears to recognize that in the case of an “obstinate infringer”—an infringer that

is not in fact willing to take a license on FRAND terms—an injunction is appropriate

and indeed necessary.3 Any other rule would create strong incentives for

intransigence by infringers in negotiation, an incentive that both undercuts the

legitimate functions served by SSOs and is contrary to the public policy of

encouraging private dispute resolution. On the other hand, the direction clearly

being taken by courts is that an injunction will not be entered on SEPs that are

subject to a FRAND commitment unless and until any defense based on a patentee’s

FRAND commitment has been adjudicated against the infringer. Indeed, a U.S. district

and appellate court have recently been willing to enjoin the enforcement abroad of an

injunction obtained in a foreign jurisdiction, until a related dispute regarding a

4

FRAND

commitment can be adjudicated.4 Negotiators are likely well aware of these widely

publicized facts, removing any credible threat that a quick, “pre-FRAND adjudication”

injunction will disrupt the infringer’s business.

Given this reality, Qualcomm does

not understand why the Commission accords substantive significance to merely

“seeking” an injunction, if this is understood to include a request for injunctive

relief in a patent infringement complaint or counterclaim. To illustrate Qualcomm’s

concern, one can imagine an SEP-holder seeking injunctive relief on a conditional

basis, noting from the outset that it is only seeking an injunction “if it is

determined that the potential licensee has refused an offer of a license on FRAND

terms”. We do not understand how such a request could be viewed as either raising an

improper threat against the infringer or bestowing inappropriate negotiating power on

the SEP-holder. And indeed, Qualcomm believes that as a practical matter any request

for injunctive or exclusionary relief based on an SEP is already impliedly subject to

this important condition.

The D&O is of course specific to the party which has agreed

to it and to the facts that gave rise to that agreement, and the Commission has not

suggested that the lengthy process spelled out by the D&O before an injunction can be

included in a “request for relief” can or should be treated as a generally applicable

model. Nor should it. Qualcomm is very concerned that this process—if applied more

broadly by the Commission or foreign governmental entities— would inefficiently delay

and fragment licensing disputes. The ordinary procedure of requesting injunctive

relief as part of the prayer for relief in a patent infringement suit—with an

injunction being awarded only after an adjudication of FRAND defenses—permits the

efficient resolution of all issues in logical sequence in a single forum, likely

providing the fastest way to a final

5

decision on all issues, and in due course

precipitating final negotiation of license terms. By contrast, the process set out in

the D&O would give obstinate infringers (or those infringers determined to delay

taking a license as long as possible) numerous additional procedural barriers to

place between themselves and any meaningful resolution or sanction for their

unreasonable or bad-faith conduct. First is the multi-month process of negotiation,

followed by offers of a license and arbitration,5 during all of which the infringer

need not engage the SEP-holder in any way. This, in turn, is followed by either

arbitration (assuming the infringer agrees to arbitrate) or litigation initiated by

the infringer for the purpose of seeking a FRAND determination if the infringer

refuses arbitration.6 An infringer could then keep the scales tilted in its favor

by pursuing the litigation in the hopes of a positive outcome, and only if there is a

finding that a FRAND offer was made and rejected would the SEP holder at last be

permitted to go to court and request an injunction.7 Only at the end of this long

chain will the infringer be put at some risk and forced to make a decision with real

consequences: either begin—at long last—to engage in good-faith negotiations, or to

put the SEP-holder to the expense and trouble of filing that new action to seek an

injunction.8 This new proceeding to establish infringement and entitlement to

6

an injunction would then likely go on for multiple

additional years. The longer the delay the greater the pressure will become on the

SEP-holder to accept something less than fair terms for a license to the patents, and

the longer the infringer’s competitors who have done the right thing in the first

instance and entered into licenses with the SEP-holder will be placed at a

competitive disadvantage. If broadly applied outside the facts, allegations, and

findings of the current D&O, the net result of these opportunities for delay and

obstruction will be to multiply litigated (or arbitrated) disputes rather than to

facilitate timely negotiated solutions.9

Certainly, there are complex issues involved

here. More than a century ago, in a context also dealing with recovery of value for

patent rights, the Supreme Court cautioned that “The vast pecuniary results involved

in such cases, as well as the public interest, admonish us to proceed with care . . .

.”10 In this regard, we note that vast numbers of licenses to SEPs have been

negotiated without litigation in the cellular industry (as well as innumerable other

standardized industries), and also without even a single instance in recent years of

an SEP-based injunction being enforced—prior to the adjudication of a FRAND

defense—against any infringer that could credibly be called a “willing licensee”.

This strong record counsels against large or abrupt changes to the surrounding legal

context.

7

When it comes to “proceed[ing] with care”, we are

also obliged to point out the absence of any economic or market crisis that could

compel or justify an abrupt change to the legal and regulatory environment in which

SEP licenses have been negotiated up to the present.11 While concern about “hold-up”

has been expressed by the Commission and a number of academic commentators, it is

notable that, under cross-examination recently, even the respected economic experts

sponsored by Microsoft (which was advancing a “hold-up” theory) were unable to

identify any instance in which hold-up had distorted the terms of a license

agreement.12 The currently front-page “smartphone wars” are sometimes pointed at as

“proof” of “a problem”, but we believe that Professor Farrell was correct when he

stated during the Commission’s workshop on patents and standards in 2011 (a time when

he was serving as the FTC’s Director of the Bureau of Economics) that:

Just because

there’s a dispute doesn’t mean that there is a breakdown of the system. Somebody

might be being unreasonable, and certainly, if you had that as a rule of general

inference or procedure, it would give whacko incentives to people to dispute

perfectly reasonable offers, okay? So, we can’t assume that the presence of a dispute

means the presence of a problem.13

Instead, given the vast size of the affected

industry, the extraordinary changes in technology, and rapidly shifting market

positions of the industry participants (including the entry of new

8

suppliers that are profiting greatly from their

participation), an outbreak of legal wrangling over intellectual property rights was

almost inevitable. Following litigation, negotiated private resolutions and license

agreements have been reached between Nokia and Apple, Apple and HTC, and Nokia and

RIM. License agreements have also been reached between industry giants Microsoft and

Samsung, in 2011, and between Microsoft and HTC, in 2010, without any litigation or

regulatory intervention at all. These are globally significant agreements between

major companies, and there is no reason to believe that other litigants in this

industry will not likewise be able to reach negotiated solutions within a reasonable

time frame, consistent with the intent underlying SSO FRAND policies.

Meanwhile, the

objective criteria indicate that the cellular industry is extraordinarily healthy and

competitive, successfully creating and passing through to consumers massive

“surplus”. Consumer uptake continues to increase rapidly: global cellular

subscriptions have risen from approximately 738 million in 2000 to almost 6 billion

today.14 The UK’s competition regulator, OfCom, has recently stated that there is $31

billion in “economic surplus” to consumers in the UK alone from 4G LTE;15 if correct,

the corresponding cumulative figure for U.S. consumers must be far larger.

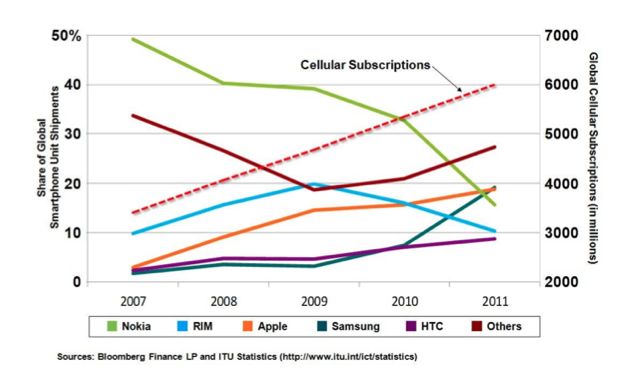

Furthermore, the industry is also characterized by transformation rather than stasis,

with the respective shares of global smartphone shipments of leading smartphone

companies shifting dramatically over recent years. For example, Apple and HTC are

highly successful “late-comer” entrants into the handset business, while Nokia,

Motorola, and RIM have seen their shares of smartphone shipments drop significantly

over the

9

last few years. As an empirical matter, it is indisputable

that existing SEP licensing practices are not preventing newcomers from competing

effectively against incumbents.

Global Shares of Leading Smartphone

Industry

Participants and Global Cellular Subscribers16

In sum, while we will not comment on

the particular conduct of the Respondent that may have prompted the terms agreed to

in this D&O, we do respectfully submit that a general policy against including

requests for injunctive relief in patent infringement suits based on SEPs, or against

actions in the ITC for exclusion orders, is not justified as a matter of logic or

empirical economics.

In sum, while we will not comment on

the particular conduct of the Respondent that may have prompted the terms agreed to

in this D&O, we do respectfully submit that a general policy against including

requests for injunctive relief in patent infringement suits based on SEPs, or against

actions in the ITC for exclusion orders, is not justified as a matter of logic or

empirical economics.

10

Qualcomm has other serious concerns, which we have raised in previous

comments in other proceedings.17 In the interest of space we will cross-reference

them here and ask that the Commission take careful note of them. First, a general

rule against “seeking” injunctions would not be well-founded as a matter of contract

law.18 Second, the Commission’s primary concern appears to be one of excessive

pricing in royalty rates, but, wholly apart from the absence of empirical support for

any systemic problem of excessive rates, this does not appear to be a proper basis

for the exercise of the Commission’s jurisdiction under Section 5.19 Finally, we

believe that any categorical threat to pursue regulatory sanctions against

SEP-holders for the simple act of “seeking” an injunction would violate the

Noerr-Pennington doctrine.20 We encourage the Commission to proceed carefully, on

a fact-specific and case-by-case basis, to guard against genuine and demonstrated

abuses, rather than attempting to rely on a regulatory construct that will for a time

confuse the industry, and that will face serious judicial challenge.

11

III. WHAT CONSTITUTES A “WILLING LICENSEE” MUST BE DETERMINED ON A

CASE-BY-CASE

BASIS

We believe that the Commission is most urgently concerned about the potential

for enforcement of an injunction against a genuinely “willing licensee[]”21 that is

operating reasonably and negotiating in good faith. This is understandable, and

stated in general terms it seems unarguable that a genuinely “willing licensee”

should not suffer injunction or exclusion, nor should it be at risk of an injunction

if the SEP-owner behaves unreasonably or in bad faith. Above, we have mentioned the

judicial safeguards currently in place that already prevent this from happening.

Here, however, we wish to note that the concept of the “willing licensee” is by no

means a simple or self-evident one, and that overly generous or naive definitions of

the “willing licensee” will create perverse incentives for infringers to act in ways

that are obstinate, non-cooperative, and outside the scope of anything that an SSO

FRAND commitment can plausibly have been meant to protect.

Interpretation of the

meaning of a FRAND commitment must not lose track of the importance of preserving

adequate incentives for investing in R&D. The ETSI IPR Policy, for example, seeks to

strike a “balance between the needs of standardization for public use . . . and the

rights of the owners of IPRs”.22 In line with this, its primary “Policy

Objectives” are to: (1) standardize “solutions which best meet . . . technical

objectives”; (2) avoid IPR essential to a standard “being unavailable”; and (3)

ensure that ETSI members and third parties are “adequately and fairly rewarded for

the use of their IPRs”.23 The only one of these that speaks directly to the

allocation of value between patentee and implementer seeks to ensure that the

12

patentee is

“adequately and fairly rewarded”; the Policy provides no support at all for the

notion that SEPs should be available to implementers “on the cheap” or at

below-market rates. And it is with this “balance” in mind that the definition of a

“willing licensee” should be considered.

Any infringer would be “willing” to take a

license if it could apply the Priceline “Name Your Own Price” principle. At the other

extreme, the vast majority of implementers in the cellular industry have proven

willing to obtain needed licenses to SEPs at prices set entirely through private

negotiation, without the intervention of courts or regulators. There is a continuum

of possibilities between these two extremes. Some may be willing to agree ex ante to

take a license on terms to be arbitrated by an impartial tribunal, along the lines of

the procedure set out in Section III of the D&O. Others may be “willing” to commit to

take a license on independently adjudicated terms only if those terms fit within

unilaterally announced parameters; otherwise, they are “unwilling” and prefer to

litigate. Some implementers may have little choice but to take a license once FRAND

issues have been decided. Other potential market entrants may take the going royalty

rates into account when deciding whether or not this industry is an attractive

opportunity given that company’s particular cost structure. An infringer may be

“unwilling” to take a license, because it insists on a substantial discount over

accepted market prices or compared to its competitors, attempting to use licensing

negotiation (and/or litigation) to obtain a competitive advantage. And of course, if

the “willing licensee” is seen as a class that enjoys the special protection of the

Commission or courts, even the infringer that is actually intent on avoiding all

payment for absolutely as long as possible will stoutly maintain that it is “willing”

to take a license . . . if only the SEP-owner would agree to “reasonable” terms.

13

What we believe is clear is that “willing” cannot be defined or proven by the mere

“say-so” of the unlicensed infringer. And, to be fair, an infringer or potential

implementer may not actually know whether it is “willing” to take a license until it

knows what the terms are. Thus, objective rules and judicial discretion need to be

applied so as to protect an infringer from fear of a “death penalty by injunction” if

the infringer negotiates in good faith, fails to reach agreement, litigates its FRAND

defense, but loses. Conversely, objective rules and judicial discretion need to be

applied so as to protect innovators and SEP-owners from opportunistic behavior by

ostensibly “willing licensees” that always claim to be willing, but instead of

negotiating in good faith to an agreement, force the SEP-owner to pursue them through

endless procedural twists and turns, hoping to avoid payment indefinitely and, if

push comes to shove, to demand at the end—after putting the patentee to vast expense

and risk—the identical terms that they should have agreed to years earlier, prior to

litigation.

IV. ARBITRATION VS. LITIGATION

Based perhaps on considerations

particular to Google and its alleged conduct, the Commission and Google have agreed

on a structure for disputes over SEP licensing terms that requires Google to offer to

resolve such disputes by binding arbitration.24 We will not presume to

second-guess that particular agreement. We are, however, concerned that this D&O may

incorrectly be viewed by some—including by foreign regulators—as a template or

guideline of general applicability. We do not believe that this could be correct.

Undoubtedly, a FRAND licensing commitment to ETSI (or to other SSOs relevant to the

cellular industry) does not contain any agreement to arbitrate future disputes, or

any waiver of the fundamental and statutory right of recourse to courts of law. And

Qualcomm

14

does not believe that the FTC has any

intention of attempting to read consent to arbitration into FRAND commitments

retroactively. But we suggest that there are also strong incentive-related reasons

why an arbitration requirement should not be made a routine component of remedies—

even when other conduct of an SEP-holder leads to an enforcement action or negotiated

consent order.

First, giving infringers a right to arbitrate will radically change

incentives during any attempt at private negotiation. In an ordinary negotiation, the

parties (more or less) look for ways to “bridge the gap”, so as to avoid the cost and

risk of litigation or arbitration. However, a common perception of the dynamics in

arbitration is that it tends to result in “split the baby” outcomes in an effort to

find the middle ground, rather than make sharper decisions clearly favoring the

position of one side over the other, even if that may be the right result. Given that

rather common perception, an infringer could negotiate the best deal it can, all the

while knowing that it can and will then use arbitration to try to obtain even

“better” terms. Further, if arbitration looms over a negotiation, then both parties

have a perverse incentive to exaggerate their demands, to increase the gap, in the

hopes that by asking for a high-ball (or low-ball) result, the final “middle ground”

ruling from the arbitrator will be at an attractive point. Of course, this posturing

will decrease the likelihood of reaching agreement through negotiation, and increase

the likelihood that arbitration will be necessary. Qualcomm does not believe that the

Commission intends or would favor such an incentive.

Second, the D&O’s provision that

an infringer may “accept” selected terms from a SEP holder’s offer, and then

arbitrate only the “unagreed” terms, is clearly a well meant attempt to narrow issues

in dispute, but in fact this misapprehends the dynamics of the good faith and

constructive negotiation of license agreements, and is instead likely to give

infringers undue

15

leverage to extract additional and unjustified value out of any

arbitration. A license agreement, like any contract, must be construed as a whole,

with no term decided or interpreted in isolation. That is especially true in the case

of portfolio license agreements in a high-tech industry, which are often quite

complex, containing multiple “value items”, including not only simple one-time

payments or royalty rates, but also cross-licenses, royalty minimums or caps,

definition of royalty base, and cooperation opportunities, such as joint development

terms, engineering support, and more. In a truly private negotiation, a party that

wishes to secure agreement will put together a carefully balanced compromise package

that includes some “gives” and some “takes”. Subsequent negotiations will therefore

involve proposed changes to both the “gives” and the “takes”. But if the other party

can lock in all the “gives” while demanding arbitration of all the “takes”, then

“package” offers become impossible.

Picture, for example, a licensing negotiation in

which the prospective licensee has indicated that it would be willing to bear unusual

risk in the form of a large, one-time, up-front payment if by doing so it could enjoy

a lower running royalty rate. Responding in good faith, the SEP-holder makes a good

faith offer including the requested low running royalty rate and a large, one-time,

up-front fee. Under the process laid out in the D&O, upon receipt of a licensing

offer from the SEP-holder, the licensee could seek arbitration of the up-front fee

alone, thereby locking in the running royalty rate, as well as any or all of the

other terms of the agreement—the very terms through which compromises are often

reached in a private negotiation. The result is that arbitration would become a tool

that infringers could use to seek better terms, without any risk of having to

compromise on other terms. And with that, no licensee would ever have a reason not to

use the arbitration procedure to try to obtain lower rates. Qualcomm is concerned

that this inevitably will make the private negotiation of license agreements more

difficult,

16

shifting the dynamic in the negotiating room from real efforts to “get

to yes” to posturing for the inevitable arbitration. Building in incentives for

parties not to reach agreement in licensing negotiations is a consequence that

everyone should want to avoid.

Third, a right to force a “selective arbitration” may

disrupt private negotiation and increase litigation for another reason. Already, the

large majority of patents being asserted in the so-called “cell phone wars” are

patents that are not even claimed to be essential. To some extent, this problem has

been limited by the common industry practice of negotiating whole-portfolio

cross-licenses, rather than SEP-only licenses, but the D&O specifically excludes

whole-portfolio cross-licenses from being part of the value exchanged in an Offer to

License.25 As a result, if SEPs generally were to become subject to restrictions

like those set out in the D&O, holders of significant numbers of non-essential

patents may choose to change strategy and refuse to negotiate whole-portfolio

licenses, opting instead for an opportunistic four-step strategy to extract licenses

to even major SEP portfolios at unfairly reduced cost:

Step 1: Bargain for an

SEP-only license on the best terms obtainable through negotiation;

Step 2: Demand

arbitration of only the price term of the SEP-only license, locking in all other

terms;

Step 3: After concluding the SEP license, assert non-essential patents against

the SEP-licensor in patent litigation or ITC actions, seeking injunctions against the

licensor’s products; and

Step 4: Use the leverage gained from actual or threatened

non- essential-patent-based injunctions to force a renegotiation of the SEP-only

license at even lower rates.

17

Again, Qualcomm

does not believe that the Commission intends this result, but it would be all too

probable should the “selective arbitration” provision of the Google D&O and the

limitation on exchanging cross-licensing value through non-essential patents become

templates for future enforcement actions by the Commission or foreign agencies.

Fourth, it is worth noting that arbitration is not an inherently superior dispute-resolution mechanism compared to litigation. Experience teaches that it is not always

faster, and not always cheaper. Often, the primary benefit that drives parties to

choose arbitration is confidentiality—a benefit that does not appear to be pertinent

to the Commission’s concerns. The D&O structure, of course, does not mandate

arbitration; it merely requires Google to offer binding arbitration. But where

arbitration is likely to be the more efficient route and both parties are acting in

good faith, SEP owners and implementers will always be free to elect arbitration, so

the efficiencies of arbitration, if any, are always within reach.

Fifth and finally,

pressure to arbitrate may have the effect of shifting away from the regular, private

negotiation of SEP royalty rates to a rate-regulation regime. Ordinarily, when a

dispute about compliance with a FRAND commitment arises, a court will decide

validity, infringement, past damages, and the FRAND-compliance of past offers. When

such a court finds that the patent is valid and infringed, that a FRAND-compliant

offer was made, and that the licensee nonetheless did not enter into a license on