Motorola has now filed its response to Apple's appeal of Judge Richard Posner's decision to toss out Apple's claims against Motorola (and vice versa), and it adds its own cross appeal [PDF] on the vice versa part -- especially challenging the implication of Judge Posner's ruling that there can be no injunctive relief for FRAND patent owners ever, as a categorical rule. A blanket denial of the right to seek injunctive relief, Motorola argues, violates patent law, contradicts eBay v. MercExchange [PDF], where the US Supreme Court held that it was error to come up with a categorical rule

that “injunctive relief could not issue in a broad swath of

cases”, and violates the original expectations of donors of technology to standards bodies. In fact, it says any such rule would violate the US Constitution, which provides that Congress shall have power to secure exclusive rights for inventors, and in the Patent Act Congress came up with, it says every grant to a patentee includes the right to exclude others. Motorola asserts that it has never waived its rights to injunctive relief and states that there is no language in its ETSI agreements requiring it to do so. Motorola argues that there should continue to be a case-by-case analysis under eBay, with judges having discretion to make such decisions based on the particular facts of each case.

Fair warning, though: the PDF is 737 pages. The actual brief is one-tenth that, 73 pages, so I've done that part of it for you as text. The rest is a collection of patents at issue, judge's orders in this case, and one from a related Apple v. Motorola litigation in Wisconsin, which is where this case began, before being transferred to Illinois and Judge Posner.

Here's how Motorola puts it: As to the denial of any injunctive relief to Motorola, the district court set forth a seemingly categorical rule against injunctions for infringement of essential patents whose holders commit to SDOs to offer licenses on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (“FRAND” or “RAND”) terms. Under this rule, the district

court declined to examine Apple’s refusal to accept a license over years of infringing use. That ruling requires this Court’s reversal, because the district court’s automatic rule that injunctions are never available for SEPs is contrary to the Patent Act, which provides injunctions as a statutory remedy; to the equitable principles of eBay; and to Motorola’s FRAND commitments to the SDOs at issue here, which did not waive its rights to injunctive relief. Subject to the terms of the FRAND commitments at issue, the same injunction rules should apply to SEPs as to all other patents, and while the traditional factors reaffirmed in eBay set a high bar, Motorola should be given the chance to surmount it.

The district court’s rulings require this Court’s vacatur or reversal because they devalue essential patents as a manner of protecting fundamental research and development, upset the settled expectations of contributors to industry standards, and create disincentives going forward for others to participate in standards development that have served consumers well for decades....

Injunctions are a remedy for patent infringement authorized by Congress. The FRAND commitments at issue in this case do not waive the right to seek injunctions and thus should not deprive Motorola of that remedy. The Constitution provides that Congress shall have power to secure exclusive rights for authors and inventors for a limited time period. U.S. Const. art. I, §8. Congress enacted the Patent Act, which provides that every patent shall contain “a grant to the patentee, his heirs or assigns, of the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States, or importing the invention into the United States. . . .” 35 U.S.C. §154(a). The Patent Act further provides that “[t]he several courts having jurisdiction of cases under this title may grant injunctions in accordance with the principles of equity to prevent the violation of any right secured by patent, on such terms as the court deems reasonable.” 35 U.S.C. §283.

The error in Motorola's view stems from viewing FRAND agreements as contracts, but if they *are* contracts, then there should be some wording about waiving injunctions, and there isn't any such language:

The district court

held that patent owners agree to license standards-essential patents on

FRAND terms “as a quid pro quo for their being declared essential to the

standard.” ... This “quid pro quo” analysis derives from Apple’s

contention that a FRAND commitment is a contract. But if FRAND commitments

are to be analyzed as contracts, principles of contract interpretation must

apply. Any contract (or commitment) that purports to deprive a patent owner

of the statutory remedies provided by Congress must clearly do so and the

ETSI policy does not. The district court’s conclusion regarding the “quid

pro quo” was incorrect. The record shows that although ETSI’s policy at one

time restricted standards-essential patent owners from seeking injunctions

in certain circumstances, that restriction was withdrawn in 1994—years

before Motorola’s patented technology was incorporated into an ETSI

standard (and over a decade before this case)....

Since 1994, the ETSI policy has contained no rule or restriction on the

availability of injunctions.... Therefore, it is

incorrect to conclude that Motorola surrendered its right to seek

injunctive relief for infringement of the patent at issue. OK, Motorola says, if we are now to view all this as a contract, let's do that a little more precisely. You can waive rights under a contract, but Motorola did not. It's there in black and white. Or rather, it *isn't* there in black and white, and in contract law, that means it doesn't exist as a requirement.

In addition, Motorola believes that the way Judge Posner decided to value patents was wrong, valuing them at their value when donated back in the Stone Ages, instead of when Apple chose to infringe, from 2007 onward. By the way, Apple is still infringing, Motorola mentions, and given how patent infringement litigation goes when it goes all the way to trial, they can string this infringement along for years and years. They already have: Apple has not historically participated in SDOs and only recently joined ETSI.... Utilizing the technology developed by Motorola and other companies, Apple entered into the cell phone market in 2007. Apple knew that Motorola owned essential patents, but released its phone without seeking a license. They didn't even try, in other words, to pay for the patents. That's not a normal launch, or it shouldn't be. I mean, they had to know what "standard-essential" means. This litigation began in 2010, three years after Apple began to infringe, as Motorola tells the history, and Apple never once offered a reasonable royalty rate. So litigation launched, and now it's 2013 and Apple still hasn't paid a penny for these patents. Apple has been knowingly infringing since 2007, six years, then, as Motorola relates.

What would happen if you rented a home and failed to pay rent for six years, ran to court instead claiming you were willing eventually to pay but not at the exorbitant rent the landlord was charging and asked the judge to set a price? And you didn't pay a dime, year after year, while the court took its time to decide if your claim that the rent was too high played out? And meanwhile, the landlord was forbidden to try to evict you? In what alternate universe does *that* happen? In USPatentWorld, where crazy is normal, and everybody loses something no matter what they do. The judge's implied ruling that owners of FRAND patents never have a right to injunctive relief, even when a licensee is unwilling, violates established law and should be overturned, Motorola argues:

This

Court should decline to adopt a categorical rule barring injunctions for

all FRAND-committed patents because that would deprive the district courts

of their discretion to fashion appropriate remedies on a case-by-case

basis. Indeed, this Court has repeatedly recognized that under eBay, the

decision to grant or deny injunctive relief rests within the discretion of

the district courts. See Edwards Lifesciences AG v. CoreValve, Inc., 699

F.3d 1305, 1314-15 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (quoting eBay, 547 U.S. at 394)

(“equitable aspects should always be considered” when deciding “whether to

grant or deny injunctive relief”); see also TiVo Inc. v. EchoStar Corp.,

646 F.3d 869, 890 n.9 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (en banc) (“[D]istrict courts are in

the best position to fashion an injunction tailored to prevent or remedy

infringement.”).

The Supreme Court in eBay also specifically noted that the

district court in that case erred in creating a categorical rule to

determine that “injunctive relief could not issue in a broad swath of

cases.” 547 U.S. at 393. Adopting such a categorical rule “cannot be

squared with the principles of equity adopted by Congress.” Id. This Court

has also found that “the fact that a patentee has previously chosen to

license the patent . . . is but one factor for the district court to

consider.” Acumed LLC v. Stryker Corp., 551 F.3d 1323, 1328 (Fed. Cir.

2008). An automatic rule prohibiting injunctions for all

standards-essential patents is

inconsistent with the equitable principles of eBay

and would divest the district courts of their discretion.

Here's a list of all the attachments, so you can find them in the PDF a little more easily:

- Order Dated January 16, 2012 (pages 92-111 of PDF - Judge Posner)

- Order Dated January 25, 2012 (pages 112-122 of PDF - Posner, summary judgment)

- Order Dated March 19, 2012 (pages 123-144 of PDF - Posner, claim construction)

- Order Dated March 29, 2012 (pages 145-151 of the PDF - Posner, means-plus-function, re Apple '949)

- Order Dated April 27, 2912 (pages 152-157 of the PDF - Posner, granting Motorola SJ on '949 ("Apple’s final equivalents argument is that “a tap is a zero-‐‑length swipe.” That’s silly. It’s like saying that a point is a zero-‐‑length line.")

- Opinion and Order Dated May 22, 2012 (pages 158-180 of the PDF - Posner, experts)

- Opinion and Order Dated June 22, 2012 (pages 181-219 of the PDF - Posner, dismissal of liability claims)

- Judgment Dated June 22, 2012 (pages 220-221 of the PDF - Clerk, judgment form)

- US Patent No. 5,946,647 (pages 222-238 of the PDF)

- US Patent No. 6,343,263 B1 (pages 239-255 of the PDF)

- US Patent No. 7,479,949 (pages 256-618 of the PDF)

- Opinion and Order Dated October 13, 2011 (pages 619-693 of the PDF - Wisconsin, Judge Barbara Crabb, claim construction of 10 Apple patents, including '559)

- Order Dated March 30, 2012 (pages 694-697 of the PDF - Posner, denial of reconsideration motion by Apple)

- Order Dated April 9, 2012 (pages 698-703 of the PDF - Posner, denial of Motorola SJ of noninfringement of '002, '263, '559, '647 patents)

- Order Dated June 5, 2012 (pages 704-708 of the PDF - Posner, grants Apple SJ of noninfringement of '559 patent)

- US Patent No. 5,319,712 (pages 709-716 of the PDF)

- US Patent No. 6,175,559 B1 (pages 717-724 of the PDF)

- U.S. Patent No. 6,359,898 B1 (pages 725-731 of the PDF)

- Order Dated May 20, 2012 (pages 732-737 of the PDF, Posner, claim construction of "forming" in claim 5 of '559 patent)

Here's the brief, as text:

*****************************

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

________________

Appeal Nos. 2012-1548, 2012-1549

_________________

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT

__________________

APPLE INC. AND NEXT SOFTWARE, INC.

(formerly known as NeXT Computer Inc.),

Appellants,

v.

MOTOROLA INC. (now known as Motorola Solutions, Inc.) AND

MOTOROLA MOBILITY, INC.,

Appellees-Cross-Appellants,

________________

Appeals from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois

in case no. 11-CV-8540, Judge Richard A. Posner

________________

RESPONSIVE AND OPENING BRIEF OF APPELLEES-CROSS-

APPELLANTS MOTOROLA MOBILITY LLC AND

MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS, INC.

________________

Kathleen M. Sullivan

Edward J. DeFranco

QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP

[address, phone]

Charles K. Verhoeven

QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP

[address, phone]

David A. Nelson

Stephen A. Swedlow

QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP

[address, phone]

Brian C. Cannon

QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP

[address, phone] 6

Attorneys for Motorola Mobility LLC and

Motorola Solutions, Inc.

[PJ: See PDF for Certificate of Interest, Addendum to it.]

i-iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES....................................ix

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT...................................1

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT.................................4

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED.....................5

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE CASE.............................6

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE FACTS............................9

A. Motorola’s Contributions To Cell Phone And Wireless

Standards....................................9

B. Apple’s Refusal To Pay FRAND Royalties On SEPs................10

C. Apple’s ‘949 Patent.....................................11

D. Apple’s ‘263 Patent.........................................13

E. Apple’s ‘647 Patent........................................14

F. Motorola’s ‘559 Patent........................................14

G. Motorola’s ‘712 Patent....................................15

H. Motorola’s 898 Patent........................................16

I. The District Court Decisions Excluding Damages Experts And

Denying Injunctive Relief.......................................16

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT..........................................17

ARGUMENT – ISSUES ON APPEAL..................................20

I. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY FOUND THAT THE ‘949

PATENT’S CLAIMS ARE

MEANS-PLUS-FUNCTION CLAIMS

BECAUSE THE CLAIMS RECITE INSUFFICIENT STRUCTURE

TO PERFORM THE CLAIMED COMPUTER FUNCTIONS....................20

v

A. The Term “Heuristics” Connotes No Definite Structure Or

Algorithm...................................................20

B. Claim 1 Of The ‘949 Patent Is A

Means-Plus-Function Claim,

As Found By The District Court.............................21

C. Claim 1

Is Invalid As Indefinite Because There Is Insufficient

Structure Recited In The Specification .........................23

D. To The Extent Sufficient Structure Is Disclosed, The District

Court

Properly Limited The Next Item Heuristic To A Right

Tap..............................................26

II. THE DISTRICT COURT MISCONSTRUED THE

‘263 TERM

“REALTIME API.”......................................28

III. THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY CONSTRUED THE

TERMS FROM THE ‘647 PATENT..................................31

A. The

District Court Correctly Construed The Term “Analyzer

Server”..................................................31

B. The District Court Correctly Construed The Phrase “Linking

Actions To The Detected Structures”................................35

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY GRANTED SUMMARY

JUDGMENT DENYING RELIEF ON APPLE’S PATENTS.................37

A. The Court Properly Excluded Apple’s Damages

Expert For

The ‘949, ‘263 and ‘647 Patents And Granted Summary

Judgment Denying Damages................................38

1. Napper Failed To Measure The Value Of The Patented

Features Of The ‘949 Patent ...............................38

2. Napper Had No Reliable Evidence To Identify Design-

Around Alternatives To The ‘263 Patent..................................39

3. Napper Improperly Valued The ‘647 Patent Based On

Facts Unrelated To This Case ..........................................40

B. The District Court Correctly Denied Apple Injunctive Relief............42

vi

1. Apple Failed to Show Any Causal Nexus To Irreparable

Harm.................................................43

2. Apple Failed To Show That Monetary Damages Are

Inadequate.................................45

3. The Balance Of Hardships Favors Motorola, And An

Injunction Would Not Be In The Public Interest......................47

ARGUMENT – ISSUES ON CROSS-APPEAL..........................................48

I. The District

Court Erred in its Claim Construction of the ‘559 Patent.........48

A. The Court Erroneously Required That The Steps Of Claim 5

Must Be Performed In Sequential Order..................................48

1. Claim 5 Does Not

Impose Any Storage Or Temporal

Requirement On The “Forming” Steps....................................49

2. Nothing In The

Specification Directly Or Implicitly

Requires Claim 5 To Be Performed In Strict Order .................50

B. The Court Read The Preferred Embodiment Out of Claim 5 .............51

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRONEOUSLY CONSTRUED THE

‘712 PATENT......................................53

III. The District Court Erred in Granting Summary Judgment of No

Damages for the ‘898 Patent...........................................56

A. Motorola’s Damages Theory Is Valid And Supported By The

Evidence............................................59

B. The District Court Improperly Discounted The Opinions Of

Motorola’s Expert Charles Donohoe................................62

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN CATEGORICALLY

BARRING INJUNCTIVE RELIEF FOR INFRINGEMENT OF

STANDARDS-ESSENTIAL PATENTS.....................................63

A. Injunctions Are A Remedy Authorized By Congress For All

Patents.......................................65

vii

B. FRAND Commitments Do Not Waive

The Right To Injunctive

Relief...........................................67

C. Imposing An Automatic Rule Barring Injunctions For

Standards-Essential Patents Upsets The Balance Between

Patent Owners And The Public.................................68

D. Motorola Should Be Allowed To Make Its Case For Injunctive

Relief At Trial..............................71

1. The District Court Failed To Apply The eBay Factors.............71

2. Material Fact Disputes Should Have Precluded The

District Court’s Ruling That Motorola Could Not Obtain

An Injunction..............................72

CONCLUSION..........................................74

Material has been deleted from pages 9, 10,

21, 46 of the nonconfidential Brief of Defendants-Cross-Appellants Motorola

Mobility LLC and Motorola Solutions, Inc. This material is deemed

confidential information pursuant to the Protective Orders entered January

28, 2011 (A1-A26) and February 1, 2012 (A596). The material omitted from

these pages contains confidential deposition testimony, confidential

business information, confidential patent application information, and

confidential licensing information.

viii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

CASES

Absolute

Software, Inc. v. Stealth Signal, Inc.,

659 F.3d 1121 (Fed. Cir. 2011).........................51

Acumed LLC v. Stryker Corp.,

551 F.3d 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2008)...........................................66

AIA Eng’g Ltd. v. Magotteaux Int’l S/A,

657 F.3d 1264 (Fed. Cir. 2011)...........................................55

Altiris, Inc. v. Symantec Corp.,

318 F.3d 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2003)....................................48

Andersen Corp. v. Fiber Composites, LLC,

474 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2007).........................................34

Apple Inc. v. Motorola Mobility, Inc.,

886 F. Supp. 2d 1061 (W.D. Wis. 2012)........................................64

Apple Inc.

v. Motorola Mobility, Inc.,

No. 3:11-cv-00178-BBC, 2012 WL 5416941, at *15

(W.D. Wis. Oct.

29, 2012)................................................68

Apple Inc. v. Motorola Mobility, Inc., No.

3:11-cv-178-BBC, 2012 WL

5943791, at *2 (W.D. Wis. Nov. 28, 2012)

Apple

Inc. v. Motorola Mobility, Inc.,

No. 3:11-cv-178-BBC, 2012 WL 5943791 (W.D. Wis. Nov.

28, 2012)...........................................71

Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd.,

678 F.3d 1314 (Fed. Cir. 2012)................................43, 45

Apple

Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd.,

695 F.3d 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2012)..............................43, 44

Applied Med. Res. Corp. v. U.S. Surgical Corp.,

435 F.3d 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2006).....................................59

ix

Aristocrat Technologies Australia PTY Ltd. v. Int’l Game Technology,

521 F.3d 1328 (Fed. Cir. 2008)..........................................20, 23, 24

Blackboard, Inc. v. Desire2Learn Inc.,

574 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2009)..............................................24

Cybersettle, Inc. v. Nat’l Arbitration Forum, Inc.,

243 Fed. Appx. 603 (Fed. Cir. 2007)................................................48

Daubert v.

Merrell Dow Pharm., Inc.,

509 U.S. 579 (1993)....................................passim

eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C.,

547 U.S. 388 (2006).........................................passim

Edwards Lifesciences AG v. Corevalve, Inc.,

699 F.3d 1305 (Fed. Cir. 2012)...............................46, 66

ePlus, Inc. v. Lawson Software, Inc.,

700 F.3d 509 (Fed. Cir. 2012)............................................23

ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH v. Canady Technology LLC,

629 F.3d 1278 (Fed. Cir. 2010)............................................64

Genentech, Inc. v. Chiron Corp.,

112 F.3d 495 (Fed. Cir. 1997)............................................54

Grain Processing Corp. v. Am. Maize-Prods. Co.,

185 F.3d 1341 (Fed. Cir. 1999)...................................61

In re Katz Interactive Call Processing Patent Lit.,

639 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2011)....................................22

Interactive Gift Express, Inc. v. Compuserve Inc.,

256 F.3d 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2001)........................................48

Lapsley v. Xtek, Inc.,

689 F.3d 802 (7th Cir. 2012).......................................61

Lewis v. CITGO Petroleum Corp.,

561 F.3d 698 (7th Cir.

2009)......................................38

x

Mangosoft, Inc. v. Oracle Corp.,

525 F. 3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2008)....................................30

Mass. Inst. Of Tech. v. Abacus Software,

462 F.3d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2006).........................................21

Merck & Co., Inc. v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc.,

395 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2005)..........................................35

On-Line Techs., Inc. v. Bodenseewerk Perkin-Elmer GmbH,

386 F.3d 1133 (Fed. Cir. 2004)........................................52

Phillips v. AWH Corp.,

415 F. 3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005).......................................30, 55

SSL Servs., LLC v. Citrix Sys., Inc.,

No. 2:08-cv-158-JRG, 2012 WL 1995514, at

*3 (E.D. Tex. June 4,

2012).....................................61

State Indus., Inc. v. Mor-Flo Indus.,

Inc.,

884 F.2d 1573 (Fed. Cir. 1989)

................................59

Stickle v. Heublein, Inc.,

716 F.2d 1550 (Fed. Cir. 1983).............................70

Storer v. Hayes Microcomputer Products, Inc.,

960 F. Supp. 498 (D. Mass.

1997)....................................22

TiVo Inc. v. EchoStar Corp.,

646 F.3d 869 (Fed. Cir. 2011)............................66

Weinberger v. Romero-Barcelo,

456 U.S. 305

(1982)......................................42

Welker Bearing Co. v. PHD, Inc.,

550 F.3d 1090 (Fed. Cir. 2008)................................22

WMS

Gaming, Inc. v. Int’l Game Technology,

184 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 1999)....................................23

STATUTES

19 U.S.C. § 1337(d)......................................67

xi

28 U.S.C. §1295(a)(1)................................4

28 U.S.C. §1331......................................4

28 U.S.C. §1338......................................4

35 U.S.C. §112......................................20, 21

35 U.S.C. §154(a)....................................65

35 U.S.C. §283....................................42, 65, 67

35 U.S.C.

§284................................................58

OTHER AUTHORITIES

In re Certain

Personal Data and Mobile Commc’ns Devices and Related

Software, Inv. No. 337-TA-710, ITC LEXIS 2874, at *34, 42 (Dec. 29,

2011)............................................41

U.S. Const. art. I, §8........................................65

RULES

Fed. R. App. P. 4(a)....................................4

Fed. R. Evid. 702................................38, 62

ADDENDUM

Order, Dated January 16, 2012 (DKT 526)......................... A40-58

Order, Dated January 25, 2012 (DKT 556).............................. A59-68

Order, Dated March 19, 2012 (DKT 671)..................................... A69-89

Order, Dated March 29, 2012 (DKT 691)....................................... A90-95

Order, Dated April 27, 2012 (DKT 826)..................................... A96-100

Order, Dated May 22, 2012 (DKT 956)...................................... A101-22

Opinion and Order, Dated June 22, 2012 (DKT 1038) ...........................A123-60

xii

Judgment, Dated June 22, 2012 (DKT 1039)...............................A161

U.S. Patent No. 5,946,647........................................ A162-77

U.S. Patent No. 6,343,263.................................. A178-93

U.S. Patent No. 7,479,949.................................. A194-555

Order, Dated October 13, 2011 (DKT 176)................................. A3312-85

Order, Dated March 30, 2012 (DKT 706) .............................A12688-90

Order, Dated April 9, 2012 (DKT 751)........................... A14702-06

Order, Dated June 5, 2012 (DKT 1003) ...............................A100146-49

U.S. Patent No. 5,319,712.................................. A100181-87

U.S. Patent No. 6,175,559.................................. A100209-15

U.S. Patent No. 6,359,898............................... A100216-21

Order, Dated May 20, 2012...............................A140427-29

xiii

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES

Prior to dismissal in November 2012,

the Court was considering Apple’s appeal of an ITC decision involving

infringement by HTC Corp. of the ‘647 and ‘263 patents at issue here, Apple

Inc. v. ITC, No. 2012-1125 (Fed. Cir. filed Dec. 29, 2011), and HTC’s

appeal from that same decision regarding the ‘647 patent, HTC Corp. v. ITC,

No. 2012-1226 (Fed. Cir. filed Feb. 24, 2012). A December 2011 ITC

exclusion order prohibited HTC from importing devices that infringe the

‘647 patent. In re Certain Personal Data and Mobile Commc’ns Devices and

Related Software, Inv. No. 337-TA-710, USITC Pub. No. 4331 (Dec. 19, 2011)

(Final). Also related to that case was Apple Inc. v. HTC Corp., No.

1:10-cv-00166- GMS (D. Del. filed Mar. 2, 2010), which was stayed pending

completion of the proceedings arising from the ITC. In November 2012, Apple

and HTC dismissed all current lawsuits pursuant to a global settlement.

This Court therefore dismissed the consolidated appeals. HTC Corp. v. ITC,

No. 12-1226, Dkt. No. 43 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 15, 2012); Apple Inc. v. ITC, No.

12-1125, Dkt. No. 48 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 15, 2012).

The ‘647 patent is also at

issue in Apple Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., No. 5:12-cv-00630-LHK

(N.D. Cal. filed Feb. 8, 2012). This Court recently considered Samsung’s

appeal of the district court’s grant of a preliminary

xiv

injunction, but

that appeal was limited to a single patent not at issue here. Apple Inc. v.

Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 12-1507 (Fed. Cir. filed July. 6, 2012). Apple has

filed a complaint against Samsung in the ITC that involves the ‘949 patent.

In re Elec. Digital Media Devices, Inv. No. 337-TA-796 (U.S.I.T.C. filed

July 5, 2011). The ITC has not issued a final determination. The target

date is currently set for August 1, 2013. Apple had also asserted the ‘263

patent against Nokia in the District of Delaware, but all claims and

counterclaims were dismissed when the parties settled. Nokia Corp. v. Apple

Inc., No. 1:09-cv-00791-GMA (D. Del. filed Oct. 22, 2009).

xv

PRELIMINARY

STATEMENT

In the almost two decades preceding Apple’s introduction of the

iPhone, Motorola—together with others in the telecommunications

industry—developed the mobile communication technology that we now take for

granted. Contributing both its patented and non-patented research and

development, Motorola worked with standards-development organizations

(“SDOs”) to improve the ability of mobile devices to transmit, receive and

process data by developing telecommunications and wireless standards that

allow different devices to operate compatibly. Motorola and others

developed large portfolios of standard-essential patents

(“SEPs”)—technology that must be licensed in order to practice a particular

standard. The system worked. Industry participants cross-licensed each

other, creating ever more efficient networks and advantages to consumers.

Apple is a relative newcomer to cellular communications. In 2007, Apple

released the iPhone, its first device that relies upon cellular

communications technology. The product has generated billions of dollars in

profits. Yet Apple has not paid one dollar for its use of Motorola’s

hundreds of fundamental patents.

The district court was correct to dismiss

Apple’s claims for infringement of three patents directed to user interface

features. The district court also correctly dismissed Apple’s claim for

damages under the Daubert standard, finding its experts’ damages theories

unreliable, because they failed to use reliable

1

benchmarks and

failed to consider reasonable design around costs. The district court also

correctly dismissed Apple’s claim for an injunction under the eBay factors,

because Apple failed to show any nexus between any irreparable harm and

infringement of its patents.

In its brief, Apple touts its user interface

design as propelling Apple’s “meteoric rise.” Apple Opening Brief (“AOB”)

at 2. But Apple ignores that it sells a cellular phone, and that its phone

uses technology developed by others. Apple’s mobile applications and user

interface design would mean nothing if Motorola and others had not invested

in the development of fundamental communications standards.

Motorola’s

cross-appeal concerns three of its SEPs: the ‘559 patent (essential to 3G

cellular standard), the ‘712 patent (essential to WiFi), and the ‘898

patent (essential to GPRS cellular standard). For the ‘559 and ‘712

patents, the district court erred in claim construction and used those

incorrect constructions to find that the patents were not infringed. For

the ‘898 patent, the district court’s claim construction was correct, but

the court nevertheless wrongly dismissed Motorola’s claims, ruling that

neither damages nor an injunction were available for Apple’s infringement.

In rejecting Motorola’s claim for damages for infringement of its SEPs, the

district court failed to take into account that patents essential to a

2

telecommunication standard are extremely valuable. Technology incorporated

into standards is voted upon by industry participants, and represents the

industry’s best available solution for standards that are adopted

worldwide. Motorola owns a portfolio of SEPs and licenses them as a

portfolio. Because of the nature of SEPs—which all cover a defined

standard, meaning an implementer of the standard infringes all patents on

that standard—has never licensed its SEPs on a patent-by-patent basis. The

best available evidence of damages for Motorola’s SEPs is therefore its

portfolio rate. Motorola submitted expert testimony that different patents

can have different contributions to the value of a standard, and that in

practice, the first patent negotiated from a portfolio may command a

disproportionate portion of the portfolio rate. The district court rejected

that theory and ruled that Motorola’s damages must be measured by valuing

the patent in question at the time right before it is contributed to the

standard—many years before Apple began infringement. This was error. The

statute provides for a “reasonable royalty” that is based on a hypothetical

negotiation occurring at the time of first infringement, not an ex ante

valuation of the patent.

As to the denial of any injunctive relief to

Motorola, the district court set forth a seemingly categorical rule against

injunctions for infringement of essential patents whose holders commit to

SDOs to offer licenses on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (“FRAND”

or “RAND”) terms. Under this rule, the district

3

court declined to

examine Apple’s refusal to accept a license over years of infringing use.

That ruling requires this Court’s reversal, because the district court’s

automatic rule that injunctions are never available for SEPs is contrary to

the Patent Act, which provides injunctions as a statutory remedy; to the

equitable principles of eBay; and to Motorola’s FRAND commitments to the

SDOs at issue here, which did not waive its rights to injunctive relief.

Subject to the terms of the FRAND commitments at issue, the same injunction

rules should apply to SEPs as to all other patents, and while the

traditional factors reaffirmed in eBay set a high bar, Motorola should be

given the chance to surmount it.

The district court’s rulings require this

Court’s vacatur or reversal because they devalue essential patents as a

manner of protecting fundamental research and development, upset the

settled expectations of contributors to industry standards, and create

disincentives going forward for others to participate in standards

development that have served consumers well for decades.

JURISDICTIONAL

STATEMENT

Motorola agrees that this Court has jurisdiction over Apple’s

appeal. Motorola timely filed its Notice of Cross-Appeal from the final

judgment. Fed. R. App. P. 4(a). The district court had jurisdiction

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§1331 and 1338, and this Court has jurisdiction over

the cross-appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1295(a)(1).

4

COUNTER-STATEMENT

OF ISSUES PRESENTED

Issues on Appeal

1. Did the district court (a) rule

correctly that the ‘949 patent’s claims are means-plus-function claims,

and, in the alternative, (b) err in failing to rule that Apple’s ‘949

patent claims—directed to ambiguous software “heuristics” for accomplishing

functions—are invalid as indefinite, because they rely on purely functional

claiming?

2. Did the district court err in its claim construction of the

term “realtime application program interface” from Apple’s ‘263 patent?

3. Did the district court correctly construe the disputed terms of

Apple’s ‘647 patent?

4. Did the district court (a) properly exclude

Apple’s damages expert for the ‘949, ‘263 and ‘647 patents for lacking

foundation to rely on the costs of non-infringing alternatives, and (b)

properly deny Apple a permanent injunction, because Apple failed to

establish irreparable harm?

Issues on Cross-Appeal

1. Did the district

court err in its construction of Motorola’s ‘559 patent?

2. Did the

district court err in its construction of Motorola’s ‘712 patent?

3. Did

the district court err in (a) granting summary judgment of no damages for

infringement of Motorola’s ‘898 patent where factual issues existed

5

that should have

been heard by the jury, and (b) excluding the reliable testimony of

Motorola’s damages experts?

4. Did the district court err in applying an

automatic rule that injunctions are never available for patents declared

essential to SDOs, and thus in declining to consider evidence that Apple

was an unwilling licensee?

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Apple released its

first cell phone—the iPhone—in 2007. It did not seek a license from

Motorola for any of Motorola’s patents related to the cellular or wireless

communication standards Motorola helped to develop, even though it is

undisputed that the iPhone leverages these same standards. Consequently,

Motorola approached Apple to initiate licensing discussions. But after

years of refusal by Apple to negotiate in good faith for a license to

Motorola’s patents, and the launch of a lawsuit by Apple against HTC

alleging infringement of a number of Apple patents by the same Android

platform that Motorola used in its offerings, Motorola filed suit against

Apple in both the district courts and the International Trade Commission.

Shortly thereafter, Apple extended its action against the Android platform

by suing Motorola in a number of venues.

This appeal arises from a

complaint that Apple filed in the Western District of Wisconsin on October

29, 2010, alleging that Motorola’s offerings infringed three Apple patents.

Motorola filed a counterclaim alleging that Apple infringed

6

six patents.

Apple then filed an amended complaint, adding twelve additional patents.

The case was transferred to the Northern District of Illinois in December

2011, with Judge Posner, sitting by designation, presiding.

This appeal

concerns a subset of the patents originally raised by the parties, namely: -

Apple’s Patent Nos. 7,479,949 (“‘949 patent”) [A194-551]; 6,343,263

(“‘263 patent”) [A178-193]; and 5,946,647 (“‘647 patent”) [A162- 177].

-

Motorola’s Patent Nos. 5,319,712 (“‘712 Patent”) [A100181-87]; 6,175,559

(“‘559 patent”) [A100209-215]; and 6,359,898 (“‘898 patent”) [A100216-221].

The district court issued a number of orders that are relevant to this

appeal: On October 13, 2011, the district court construed the phrase

“transmit overflow sequence number” in Motorola’s ‘712 patent, holding that

it cannot be transmitted to the receiver. A333-3341.

On January 16, 2012,

the district court provided initial claim constructions for Apple’s ‘949

patent in its summary judgment order, finding that the ‘949 patent claims

“gesture towards” the step-by-step process required for means-plus-function

claims. A45-47.

7

On January 25, 2012, the Court construed “realtime application

program interface,” in Apple’s ‘263 patent to mean: “API that allows

realtime interaction between two or more subsystems.” A66-68.

On March 19,

2012, the district court construed claim 5 of Motorola’s ‘559 patent,

A85-86, and certain terms in the ‘647 patent, A76-79. The Court also held

that the claims of the ‘949 patent were means-plus-function claims. A80-83.

On March 29, 2012, the Court provided a supplemental claim construction

order for Apple’s ‘949 patent, where the Court determined the structure in

the specification for each claim. A90-95. The district court denied Apple’s

motion for reconsideration of the court’s claim construction for the ‘949

patent on March 30, 2012. A12688-90.

On April 27, 2012, the Court granted

in part Motorola’s renewed motion for summary judgment of non-infringement

of Apple’s ‘949 patent. A96-100.

On May 20, 2012, the district court

construed an additional limitation in claim 5 of the ‘559 patent, holding

that the “forming” steps in the patent must be performed in order.

A140427-29.

On May 22, 2012, the Court struck the damages experts of both

sides, ruling that neither party’s expert had presented sufficiently

rigorous damages analyses. A101-122.

8

[Confidential Material Omitted]

The

Court granted Apple summary judgment of non-infringement for claim 5 of the

‘559 patent on June 5, 2012. A100146-49.

On June 22, 2012, the Court

granted both sides summary judgment on the grounds that neither side was

entitled to monetary or injunctive relief. A123-160. The court dismissed

the cases in their entirety. Id.

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

A. Motorola’s Contributions To Cell Phone And Wireless Standards

Motorola has been a pioneer in phone and radio technology, and was

responsible for the first-ever commercial portable cellular telephone in

1983. A118036-37. As part of that research and development, Motorola has

participated in approximately 30 SDOs, including the European Technical

Standards Institute (“ETSI”). A117796. Members of SDOs like Motorola work

together to determine technical solutions enabling interoperability among

manufacturers’ products and then implement those solutions into standards.

Sometimes, those standards use patented technology. A117793. When member

companies declare their patents essential to a standard, often they agree

to license those patents on FRAND/RAND terms. A117794, A117797-98.

Motorola

has successfully negotiated and entered into cross licenses for its

standards essential patents with [redacted]

9

[Confidential Material Omitted]

[redacted]

Motorola’s portfolio

has generated [redacted] in royalties and, through cross-licensing, additional

value in the form of freedom of operation for Motorola to develop its own

mobile devices. A118883.

B. Apple’s Refusal To Pay FRAND Royalties On

SEPs

Apple has not historically participated in SDOs and only recently

joined ETSI. A117800. Utilizing the technology developed by Motorola and

other companies, Apple entered into the cell phone market in 2007. A117800.

Apple knew that Motorola owned essential patents, but released its phone

without seeking a license. A117801.

Shortly after Apple released the first

generation iPhone in the summer of 2007, Motorola reached out to Apple to

initiate cross-license discussions. A117802. Motorola offered to license

its standards essential portfolio to Apple in exchange for a 2.25% royalty

on licensed sales, the same proposal Motorola has made to dozens of other

companies. A118883-85. But Apple made plain at the parties’ initial meeting

that it had no intention of taking a license. A104856.

10

Motorola

continued to seek to license its portfolio to Apple, but for years Apple

resisted taking a license, rejected Motorola’s proposals, and refused to

provide any counter-offer. A118885-86. Up through the fall of 2010, when

Motorola filed this lawsuit, Apple had still failed to make any reasonable

licensing proposal.

C. Apple’s ‘949 Patent

Apple’s ‘949 patent claims

“heuristics” for translating finger movements on a touchscreen device into

computer commands. A194-555. Apple asserted claim 1 and dependent claims 2,

9 and 10. A4799. Claim 1 of the patent provides:

A computing device,

comprising: a touch screen display; one or more processors; memory; and

one

or more programs, wherein the one or more programs are stored in the memory

and configured to be executed by the one or more processors, the one or

more programs including:

instructions for detecting one or more finger

contacts with the touch screen display;

instructions for applying one or

more heuristics to the one or more finger contacts to determine a command

for the device; and

instructions for processing the command;

wherein the

one or more heuristics comprise:

a vertical screen scrolling heuristic for

determining that the one or more finger contacts correspond to a one-

dimensional vertical screen scrolling command rather

11

than a two-dimensional

screen translation command based on an angle of initial movement of a

finger contact with respect to the touch screen display;

a two-dimensional

screen translation heuristic for determining that the one or more finger

contacts correspond to the two-dimensional screen translation command

rather than the one-dimensional vertical screen scrolling command based on

the angle of initial movement of the finger contact with respect to the

touch screen display; and

a next item heuristic for determining that the

one or more finger contacts correspond to a command to transition from

displaying a respective item in a set of items to displaying a next item in

the set of items.

A549-50.

At claim construction, the district court

adopted Apple’s definition of heuristics as “one or more rules to be

applied to data to assist in drawing inferences from that data.” A45-47.

But the court construed the ‘949 heuristic elements as means-plus-function

claims, finding: “Apple’s patent cannot cover every means of performing the

function of translating user finger movements into common computer commands

on a touch-screen device—that would be a patent on all touch-screen

computers.” A83.

Following the court’s claim construction rulings, Motorola

filed a renewed motion for summary judgment, A14713-49, which the court

granted in large part.

12

A96-100. The remainder of the case concerning the

‘949 patent was dismissed due to Apple’s failure to prove any

damages.1 A123-61.

D. Apple’s ‘263 Patent

Apple’s ‘263 patent relates

to a system to perform “realtime” services using a “realtime API” allowing

the host processor to interact with the realtime subsystem. A178-93.

Claim 1 of the patent provides:

1. A signal processing system for providing

a plurality of realtime services

to and from a number of independent client

applications and devices, said system

comprising:

a subsystem comprising a

host central processing unit (CPU) operating in accordance with at least

one application program and a device handler program, said subsystem

further comprising an adapter subsystem interoperating with said host CPU

and said device;

a realtime signal processing subsystem for performing a

plurality of data transforms comprising a plurality of realtime signal

processing operations; and

at least one realtime application program

interface (API) coupled between the subsystem and the realtime signal

processing subsystem to allow the subsystem to interoperate with said

realtime services.

A190. The district court adopted Apple’s proposed

construction for “realtime API,” A66-68, and denied Motorola’s motion for

summary judgment of non- infringement, A14702-06.

13

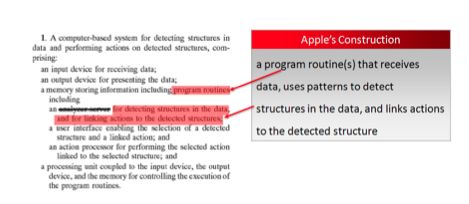

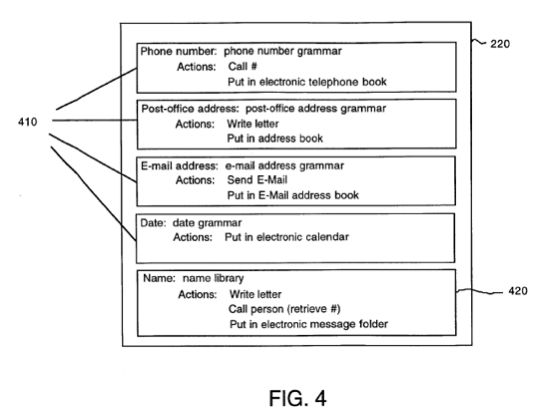

E. Apple’s ‘647 Patent

Apple’s ‘647 patent is directed to a

system that detects “structures” (e.g., phone numbers) in documents, links

user actions to those structures, and provides users with the ability to

select one of those actions. A162-77. Claim 1 provides:

A computer-based

system for detecting structures in data and performing actions on detected

structures, comprising:

an input device for receiving data;

an output

device for presenting the data;

a memory storing information including

program routines including

an analyzer server for detecting structures in

the data, and for linking actions to the detected structures;

a user

interface enabling the selection of a detected structure and a linked

action;

and an action processor for performing the selected action linked

to the selected structure; and

a processing unit coupled to the input

device, the output device, and the memory for controlling the execution of

the program routines. A176.

The Court adopted Motorola's proposed constructions for the term "analyzer

server” and the phrase “linking actions to the

detected structures.” A76-79.

F. Motorola’s ‘559 Patent

Motorola’s ‘559

patent covers important aspects of 3G technology, and allows mobile devices

to initiate communications with cellular stations more

14

effectively.

A118080. Claim 5 of the ‘559 patent is dependent on claim 1 and provides:

5. A method for generating preamble sequences in a CDMA system, the method

comprising the steps of:

forming an outer code in a mobile station;

forming

an inner code in the mobile station utilizing the following equation:

where

sj, j=0,1, . . .,M-1 are a set of orthogonal codewords of length P, where M

and P are positive integers; and

multiplying the outer code by the inner

code to generate a preamble sequence.

A100215. The Court adopted Apple’s

proposed constructions, A86, and then granted summary judgment of

non-infringement, A14703, A100146.

G. Motorola’s ‘712 Patent

Motorola’s

‘712 patent covers certain WiFi technology. A108970-71. Claim 17 of the

‘712 patent provides:

17. In a communication system having a physical

layer, data link layer, and a network layer, a method for providing

cryptographic protection of a data stream, comprising:

(a) assigning a

packet sequence number to a packet derived from a data stream received from

the network layer;

(b) updating a transmit overflow sequence number as a

function of the packet sequence number; and

15

(c) encrypting, prior to communicating

the packet and the packet sequence number on the physical layer, the packet

as a function of the packet sequence number and the transmit overflow

sequence number.

A100186. The Court adopted Apple’s proposed construction,

A3340-41, and then granted summary judgment to Apple of non-infringement.

A40-42.

H. Motorola’s 898 Patent

The ‘898 patent is directed to a method

in which a mobile device informs a cellular station of when it can expect

the mobile to be finished with a transmission. It provides greater advanced

warning to the cellular station of the impending completion of a

transmission than prior art methods did.

I. The District Court Decisions

Excluding Damages Experts And

Denying Injunctive Relief

The district court

excluded Apple’s damages expert Brian Napper from offering testimony

regarding Apple’s patents. A116-17, A119. The court found that Napper

failed to exercise the same level of intellectual rigor as would be used in

the field outside litigation. A111-119. The court also found that Apple

could not prove irreparable harm, or that the balance of harms favored

granting an injunction, because Apple’s patents related to only minor

features in the accused products. A155-57.

The district court also excluded

Motorola’s damages expert Carla Mulhern, and her testimony regarding

damages for the ‘898 patent based on a portion of the established portfolio

rate. A121. In addition, the court excluded portfolio

16

licensing expert

Charles Donohoe’s declaration. A138-39. As a result, the court granted

Apple’s motion for summary judgment of no damages for the ‘898 patent.

A140. Finally, the court granted Apple’s motion for summary judgment that

Motorola could not obtain an injunction on the ‘898 patent, because it was

a standard essential patent, without regard to the standard commitment

Motorola had made or the evidence of Apple’s refusal to negotiate in good

faith. A140-143.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The ‘949 Patent: The asserted claims

of the ‘949 patent do not contain sufficient structure (in this case a

computer algorithm) to perform the functions specified in the claims. As a

result, the district court correctly determined that the “heuristic”

elements in these claims must be interpreted as means-plus-function claims.

The district court erred in part, however, in its identification of the

corresponding structure from the specification for performing the claimed

function, because the specification did not provide sufficiently definite

structure linked to the claimed functions.

The ‘263 Patent: The district

court improperly construed the term “realtime API.” The court should have

found that a “realtime API” must itself have “realtime” functionality by

placing specific time constraints on the execution of the API. Some of the

claims of the patent recite a “realtime API” providing the interface

between applications and the realtime subsystem, while others recite an

17

API

without the modifier “realtime” providing the same interface. This dictates

a distinction between “realtime” API’s and other API’s, which the district

court’s construction eliminates.

The ‘647 Patent: The district court

properly construed “analyzer server” in Apple’s ‘647 patent. Intrinsic

evidence supports the court’s construction. The district court also

properly construed “linking actions to the detected structures.”

Apple’s

Damages and Injunction Claims: The district court properly excluded the

expert opinions of Apple’s damages expert Brian Napper. Napper’s damages

opinions failed the basic prerequisites to survive Daubert.

The district

court also correctly found that Apple was not entitled to permanent

injunctive relief. Apple’s patents relate to only minor features in the

accused products, and there is no evidence in the record of any causal

nexus to any irreparable harm from their infringement.

The ‘559 Patent: The

district court improperly construed Motorola’s ‘559 patent, because it held

incorrectly that the steps in the patent must be performed in specific

sequence, and determined that the same codeword cannot be repeated, which

excludes the preferred embodiment.

The ‘712 Patent: The district court

erred in its construction of “transmit overflow sequence number” by ruling

that it can never be transmitted by the

18

wireless device to the receiver,

improperly relying on non-contemporaneous extrinsic evidence.

Ruling of No

Available Damages for the ‘898 Patent:

The district court improperly

rejected Motorola’s claim for damages. The district court improperly

required Motorola to value its patent ex ante—at the time right before the

standard was adopted, years before Apple’s infringement. This Court’s

precedent requires that a reasonable royalty be determined as of the time

of first infringement—at which point Motorola’s FRAND commitments and

cross-licensing considerations would be taken into account—but the district

court failed to apply this standard.

Availability of Injunctions for

Standards-Essential Patents:

The district court improperly held that

Motorola could not obtain an injunction on the ‘898 patent, which is

essential to the GPRS standard and subject to FRAND commitments carefully

defined by ETSI. Without referencing the actual terms of the ETSI

commitments (which include no prohibition on seeking injunctions), the

court ruled that the holder of SEPs is categorically unable to obtain

injunctive relief against willful infringers. The traditional eBay factors

should apply to SEPs, just as is the case with any other patent.

19

ARGUMENT – ISSUES

ON APPEAL

I. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY FOUND THAT THE ‘949

PATENT’S

CLAIMS ARE MEANS-PLUS-FUNCTION CLAIMS

BECAUSE THE CLAIMS RECITE

INSUFFICIENT STRUCTURE

TO PERFORM THE CLAIMED COMPUTER FUNCTIONS.

Apple’s

appeal on the ‘949 patent should be rejected because the district court

correctly found the heuristic elements of claim 1 should be interpreted as

means-plus-function, A80-83, and because there is no structure or algorithm

recited in the claims by which the claimed computer system could perform

the claimed heuristic functions. 35 U.S.C. §112, ¶6. Pure functional

claiming of computer functions without recitation of an algorithm would

render the claim indefinite. Aristocrat Technologies Australia PTY Ltd. v.

Int’l Game Technology, 521 F.3d 1328, 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

A. The Term

“Heuristics” Connotes No Definite Structure Or

Algorithm

Claim 1 of the

‘949 patent claims “instructions for applying” three “heuristics for

determining” how to perform certain functions—vertical screen scrolling

versus two-dimensional screen translation, and moving to the next item.

A549-50. Nowhere in the patent is the term “heuristic” defined. A194-555.

In its brief, Apple deems heuristics “engineer-speak for rules applied to

data . . . to assist in drawing inferences . . . from that data.” AOB 7

(emphasis added). Apple’s vague reference to “engineer-speak” is telling.

Claims are written for those of ordinary skill in the art, i.e., software

engineers in this instance. But none of the

20

[Confidential Material Omitted]

named

engineer inventors could define what “heuristics” meant. When asked to

define heuristics at his deposition, inventor Paul Marcos said [redacted]

A5054 at

15:23-24. Named inventor Scott Herz answered that [redacted] A5046 at 95:20-96:16.

“Heuristics” is an imprecise concept that does nothing to delineate a

particular structure or algorithm to perform the recited function.

Therefore, unless the term is interpreted in means-plus-function fashion,

claim 1 does not cover a specific invention but merely refers to an idea

for an invention. This is improper functional claiming. See, e.g., Mark

Lemley, Software Patents and the Return of Functional Claiming (July 25,

2012), Stanford Public Law Working Paper No. 2117302, available at

http://ssrn.com/abstract=2117302 (last visited March 12, 2013). Such

functional claiming fails to put the public on notice of what is covered by

each patent, which stifles innovation.2

B. Claim 1 Of The ‘949 Patent Is

A Means-Plus-Function Claim, As

Found By The District Court

If a claim

limitation does not use the words “means” or “means for,” there is a

rebuttable presumption against construing the limitation as

means-plus-function.

21

Mass. Inst. Of Tech. v. Abacus Software, 462 F.3d

1344, 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2006). This presumption can be overcome if a claim

“fails to recite sufficiently definite structure or else recites function

without reciting sufficient structure for performing that function.” Id.

(internal quotations and citations omitted).

For example, in Welker Bearing

Co. v. PHD, Inc., this Court determined that the claim limitation at issue

should be construed as means-plus-function, even though the limitation did

not use the word “means.” 550 F.3d 1090, 1095-1097 (Fed. Cir. 2008). This

Court noted that “the generic terms mechanism, means, element, and device,

typically do not connote sufficiently definite structure [to avoid

means-plus-function treatment] . . . The term mechanism standing alone

connotes no more structure than the term means.” Id. at 1096 (internal

quotations omitted) (emphasis removed).

The term “heuristic” is similarly

generic; it encompasses any and all rules for accomplishing the function

set forth in the claims. See, e.g., Storer v. Hayes Microcomputer Products,

Inc., 960 F. Supp. 498, 502-503, n. 5 (D. Mass. 1997) (equating a

“heuristic” to an “algorithm,” “method,” or “means.”) The law is

well-settled that, when a generic function of a general purpose computer is

recited in the claims without sufficient structure claimed to perform the

function, the claim must be interpreted to incorporate the specific

algorithm recited in the specification linked to the claimed function. In

re Katz Interactive Call Processing Patent Lit.,

22

639 F.3d 1303,

1314-15 (Fed. Cir. 2011). See also ePlus, Inc. v. Lawson Software, Inc.,

700 F.3d 509, 518-19 (Fed. Cir. 2012); WMS Gaming, Inc. v. Int’l Game

Technology, 184 F.3d 1339, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

Apple attempts to find

structure in the claim by pointing out the other generic limitations, which

include a “computing device” with a touchscreen, processors, memory and

unspecified programs. AOB 26. A “computing device” is insufficient

structure within the claim, as every software patent requires some type of

computing device. A generic computer alone does not describe the structure

needed to carry out the described function. Aristocrat Technologies, 521

F.3d at 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Claim 1 of the ‘949 patent therefore should

be analyzed as a means-plus-function claim, looking to the specification to

determine whether sufficient structure exists for the claim to survive.

C. Claim 1 Is Invalid As Indefinite Because There Is Insufficient

Structure Recited In The Specification

The district court was correct that

the heuristic elements of claim 1 should be construed as

means-plus-function claims. However, as alternative grounds for affirmance

of judgment in favor of Motorola on the ‘949 patent, this Court should hold

that the district court was incorrect in finding that there was sufficient

structure in the specification linked to each of the claimed functions.

“If

the specification is not clear as to the structure that the patentee

intends to correspond to the claimed function, then the patentee has not

paid the price but

23

is attempting to claim in functional terms unbounded by any

reference to structure in the specification.” Aristocrat Technologies, 521

F.3d at 1333 (citation omitted). “That ordinarily skilled artisans could

carry out the recited function in a variety of ways is precisely why claims

written in ‘means-plus-function’ form must disclose the particular

structure that is used to perform the recited function.” Blackboard, Inc.

v. Desire2Learn Inc., 574 F.3d 1371, 1385 (Fed. Cir. 2009). Without

claiming a definite structure, a patentee is attempting “to capture any

possible means for achieving that end.” Id.

In Aristocrat, this Court was

unable to find structure for the function “‘pay[ing] a prize when a

predetermined combination of symbols is displayed in a predetermined

arrangement of symbol positions selected by a player[.]’” 521 F.3d at 1334.

Figure 1 and Table 1 in the patent provided examples of how player

selections could translate to possible winning combinations, but that was

not sufficient. They were “at most, pictorial and mathematical ways of

describing the claimed function of the game control means. That is not

enough to transform the disclosure of a general-purpose microprocessor into

the disclosure of sufficient structure to satisfy section 112 paragraph 6.”

Id. at 1335. Therefore, this Court found that the claims were invalid.

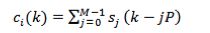

The

description of the way to perform the claimed heuristic functions in the

specification of the ‘949 patent is similarly deficient. The structure

identified by

24

the district court for the vertical screen scrolling and

two-dimensional translation heuristics, Figure 39C, contains only one

dotted arrow with the notation “o” and another dotted arrow with the

notation “>27o.”

A345. Nowhere in the figure or elsewhere in the

specification does the patent outline any of the rules or parameters that

must be considered to implement these functions, (such as speed,

acceleration or distance traveled by the measured input), nor does it

explain how to determine the “angle of initial movement.” See A194- 555.

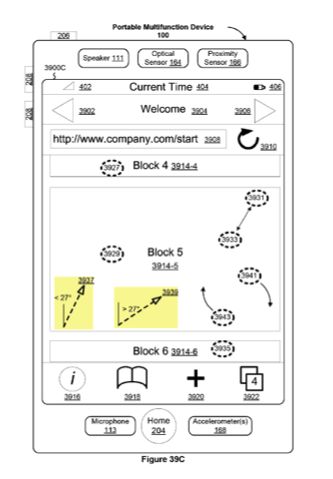

The same is true for the alleged structure of the next item heuristic,

Figure 16A, which contains merely a dotted arrow (1616) and a dotted circle

(1620).

25

A229. The specification notes myriad variables that may be analyzed to

interpret the characteristics of finger gestures (e.g., speed,

acceleration), but does not disclose an algorithm that uses these variables

to interpret a finger gesture as a next item command. A496 col. 15:10-13.

Claim 1 is therefore invalid as indefinite.

A229. The specification notes myriad variables that may be analyzed to

interpret the characteristics of finger gestures (e.g., speed,

acceleration), but does not disclose an algorithm that uses these variables

to interpret a finger gesture as a next item command. A496 col. 15:10-13.

Claim 1 is therefore invalid as indefinite.

D. To The Extent Sufficient

Structure Is Disclosed, The District Court

Properly Limited The Next Item

Heuristic To A Right Tap

To the extent there is sufficient structure

disclosed in the specification corresponding to any of the claimed

heuristic functions, the district court properly held that the next item

heuristic must be limited to a tap on the right side of the

26

screen, rather

than a “swipe” from right to left. An algorithm corresponding to the next

item heuristic must be able to determine whether a particular gesture is

intended to be a next item command. A necessary corollary to this is that

the algorithm must be able to determine that a given gesture corresponds to

one command (e.g., a next item command) rather than a different command

(e.g., a horizontal screen scrolling command).

Apple argues, AOB 31, that

the district court erred in its premise that claim 1 requires that “a

horizontal finger swipe should be interpreted as a command to shift the

screen horizontally.” A93. In Apple’s view, claim 1 instead covers a

“‘two-dimensional’ (diagonal) swipe,” which it argues is different than a

horizontal swipe. AOB 31-32. This argument has no support in the patent. On

the contrary, Figure 39C shows that a vertical screen scrolling command

will be implemented if the user’s angle of initial finger movement is less

than 27o, and that all movements at an angle greater than 27o will

implement a two-dimensional screen translation command. A345. By

definition, a horizontal 90o swipe would fall within this threshold and

would trigger a two-dimensional translation command.

Apple is also

incorrect that the district court “appears to have confused claim 1 with

dependent claim 10, which does cover a situation where a horizontal swipe

may lead to a ‘one-dimensional horizontal screen scrolling command.’” AOB

32. Apple made this argument in its motion for reconsideration of the

district court’s

27

order, and the district court rejected it, stating “[a]t page 4

of my opinion I compare the next item heuristic not to claim 10’s

horizontal screen scrolling function, but to claim 1’s diagonal translation

function.” A12689. The district court found the “inconsiderate sloppiness”

of Apple’s “flagrant misreadings” of the district court’s order to be

“unprofessional and unacceptable,” yet Apple attempts to advance the same

arguments again here. A12689-90.

Apple has also waived its argument that

“the patent does not describe a device where ‘the same user finger movement

is understood to communicate two separate commands’ at the same time,” AOB

32. While Apple argues that “the district court misunderstood the

invention,” AOB 22, in fact, Apple did not raise this argument until its

motion for reconsideration of the district court’s claim construction

regarding the next item heuristic; at that time, the district court

“decline[d] to consider the merits” of the argument, because “Apple failed

to advance [the waived argument] anywhere in its briefing of the

construction of the ‘949 patent prior to this motion to reconsider,” and

Apple therefore forfeited it. A12690.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT

MISCONSTRUED THE ‘263 TERM

“REALTIME API.”

The district court construed the

term “realtime API,” as recited in claims 1 and 2 of Apple’s ‘263 patent to

mean: “API that allows realtime interaction between two or more

subsystems.” A68. To the extent this Court reverses the

28

district court’s

rulings relating to damages and injunctive relief on the ‘263 patent, it

should reverse its construction of “realtime API”, because it reads the

“realtime” limitation on the API itself out of the claim.

The ‘263 patent

claims recite at least two API types that interoperate with realtime

devices. The first type, recited in claim 1 and at issue here, is a

realtime API: “at least one realtime application program interface (API)

coupled between the subsystem and the realtime signal processing subsystem

to allow the subsystem to interoperate with said realtime services.” A190

col. 11:39-42. The other type, recited in independent claim 31, is an API

without any realtime requirement: “at least one application programming

interface for receiving the requests generated by said device handler

program and issuing commands to said realtime engine to perform the

requested data transformations.” A191 col. 14:40- 43 (emphasis added).

The

APIs of both claims 1 and 31 allow for realtime operations of other

components by providing an interface to the realtime subsystem, per the

express language of the claims. But the realtime API of claim 1 also must

itself be realtime.3

29

The inventors’ deliberate use of the

“realtime” modifier within the claim confirms that “realtime” elements must

have realtime functionality. See Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1314

(Fed. Cir. 2005) (use of the word “steel” in the term “steel baffles” of

the claim “strongly implies” a difference between steel baffles and other,

non-steel baffles).

The district court’s construction requires the

“realtime API” to “allow[ ] realtime interaction between two subsystems,”

A68, which facially might suggest that the “realtime” modifier for the API

is addressed by the construction. But a closer look reveals otherwise.

Claim 1 independently requires the claimed realtime API “to allow the

subsystem to interoperate with said realtime services,” meaning that the

“realtime” modifier of the API in the claim must provide an additional

limitation. Indeed, this Court rejects constructions where they would

“ascribe[ ] no meaning to the term . . . not already implicit in the rest of

the claim.” Mangosoft, Inc. v. Oracle Corp., 525 F. 3d 1327, 1330-31 (Fed.

Cir. 2008).

Motorola proposed two constructions for this term: - “an API

that itself has defined upper bounded time limits”4

- “API facilitating

constant bit rate data handling”

A6351-68.

30

The International Trade Commission, in the dispute

between Apple and HTC involving the ‘263 patent, adopted the following

construction: “an API that operates in realtime, i.e., as an API that

operates with a defined upper bonded time limit.” All of these

constructions address the notion that the API itself must be “realtime,”

and for that reason, any are acceptable.

III. THE DISTRICT COURT

CORRECTLY CONSTRUED THE TERMS

FROM THE ‘647 PATENT.

The district court

construed two terms from Apple’s ‘647 patent: “analyzer server” and

“linking actions to the detected structures.” A76-79.

A. The District

Court Correctly Construed The Term “Analyzer

Server”

The district court

adopted Motorola’s proposed construction for the term “analyzer server,”

construing it as “a server routine separate from a client that receives

data having structures from the client.” A78.

In adopting Motorola’s

construction, the district court relied on the claim language—particularly

the meaning of “server” to one of ordinary skill in the art5

—and the only

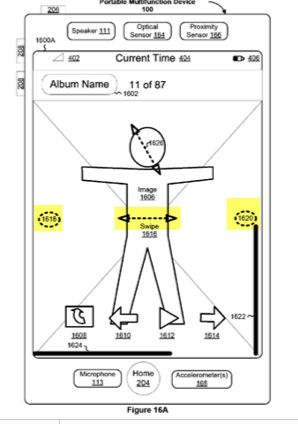

embodiment described in the specification. A77-78. The ‘647 patent

describes “the program 165 of the present invention,” which contains the

31

analyzer server, as being depicted in Figure 1 (A174 col.

3:37-44) separate from the “[a]pplication 167”:

A163. On appeal, Apple

presents no conflicting evidence about the meaning of the term “server” or

the description of the “analyzer server” in the intrinsic evidence. Indeed,

Apple acknowledges that the preferred (and only) embodiment in the patent

shows that the analyzer server is separate from the client applications,

AOB 35, consistent with a “client-server” model. Instead, Apple claims that

the ITC and district court have “issued conflicting constructions.” AOB at

33-34. That is incorrect. In the ITC case in question—which involved HTC,

not Motorola—the

32

parties agreed to a construction of “analyzer server.”6 That

construction was not evaluated by either the ALJ or the Commission.

Regardless, any ITC decision would not be binding here, and thus Apple did

not even raise the ITC proceedings with the district court.

Apple’s claim

differentiation argument also fails. Apple argues that, under the district

court’s construction, dependent claims 3 and 10 improperly cover the same

subject matter of claim 1. AOB 35. But Apple is wrong.

Claim 3 recites that

“the input device receives the data from an application running

concurrently.” A176 col. 7:27-28. Moreover, claim 3 recites that the

“program routines stored in memory further comprise an application program

interface for communicating with the application.” Id. at 7:29-31. Claim 10

recites a different application that “causes the output device to present

the data received by the input device,” and “an application program

interface that provides interrupts and communicates with the application.”

Id. at 7:58-61.

The system of claim 1 is broader than dependent claim 3,

because its input device can receive data from an application running

concurrently or not concurrently, and it can work with or without an

application program interface. The system of claim 1 is similarly broader

than dependent claim 10, because it can

33

work with or without the recited application and

application program interface of claim 10. In light of these distinctions,

any claim differentiation argument fails. Andersen Corp. v. Fiber

Composites, LLC, 474 F.3d 1361, 1369-71 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (rejecting claim

differentiation arguments where there were differences in scope between the

claims in question).

Finally, Apple proposes its own construction—one that

would eliminate the “server” concept entirely and swap it out in favor of

the broader, generic term “program routine”:

If claim 1 was not intended to

require a server, the patentees could have drafted the claims to recite a

“program routine” for performing the various “detecting,” “linking,”

“enabling,” and “performing” steps without further clarification. Indeed,

they did so in claims 13, 14, and 15. A176 col. 8:1-33. They included the

term “server” in claim 1 because it has a specific meaning—a separate

component that serves various clients. “A claim construction that gives

meaning to

34

all the terms of the claim is preferred over one that does not

do so.” Merck & Co., Inc. v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., 395 F.3d 1364, 1372

(Fed. Cir. 2005).

B. The District Court Correctly Construed The Phrase

“Linking

Actions To The Detected Structures”

The district court adopted

Motorola’s proposed construction for the phrase “linking actions to the

detected structures,” construing the phrase as “creating a specified

connection between each detected structure and at least one computer

subroutine that causes the CPU to perform a sequence of operations on that

detected structure.” A78-79.

Apple complains that the district court’s

construction—and in particular the “specified connection” language—is

improperly based on the ‘647 specification’s reference to “pointers,” which