|

|

| Allen v. World - The Fight Over Claim Construction |

|

|

Tuesday, October 30 2012 @ 02:00 PM EDT

|

Interval Licensing's infringement suit against AOL, Apple, Google and Yahoo! moves forward, the stay pending the USPTO reexamination outcome having been lifted. Now it is on to claim construction, and not surprisingly the parties have highly divergent views of what the claims mean or if they mean anything whatsoever (i.e., they are ambiguous).

Interval insists all is clarity and all is well. The Defendants, not so much. At issue are 15 terms used in U.S. Patent Nos. 6,034,652 and 6,788,314. Interval insists the Defendants "over and

over again, [they] attempt to add language to the definition in an attempt to create ambiguity and

unnecessarily change the scope of the claims in ways unsupported by the specification and claim

language." However, both parties agree the patents are about providing "information to a user in non-distracting

ways that do not interfere with the user’s primary activity on a device such as a computer."

First up is the issue of the claim recitation that the "images must be displayed in an “unobtrusive manner." Second is the issue of the claim recitation that the "display of images must not “distract a user” from the user’s “primary interaction”

with the apparatus." Defendants insist these are nebulous concepts, subjective in nature, and impossible to quantify to the measurable extent required for patent protection, i.e., the claims are indefinite. Interval, in its original claim construction brief (300 [PDF; Text]) essentially ignores this fundamental issue before moving directly to the 15 disputed terms. For their part, the Defendants in their original claim construction brief (301 [PDF; Text]) observe that these issues are fundamental and must be addressed before moving to the 15 specific disputed terms.

Defendants argue that the ambiguity/indefiniteness of these two terms "render[s] the claims of the ’314 Patent and claims 4-8, 11, 34, and 35 of

the ’652 Patent invalid." Relying on the Halliburton and Datamize cases, Defendants find two criteria establishing indefiniteness:

First, a

term is indefinite if one skilled in the art would not know from one use to the next whether the

accused product was within the scope of the claims because outside factors affect whether the

limitation is met.

...

Second, claim language that “depend[s] solely on the unrestrained, subjective opinion of

a particular individual purportedly practicing the invention” is indefinite. ... When a subjective claim term is used, “[s]ome objective standard must be provided in

order to allow the public to determine the scope of the claimed invention.”

This argument appears to have some merit. What is obtrusive or unobtrusive. Won't that standard be different for each individual? Likewise, what is distracting or not distracting. As Defendants argue, aren't these essentially issues of what is "aesthetically pleasing." Compounding Interval's problem with these two terms is the fact that Interval's own expert admitted "that two users presented

with the identical displayed image may reach different conclusions about whether the image was

displayed in an “unobtrusive manner” confirms the inherent subjectivity of this term [unobtrusive]." Further, that same expert "confirmed that

many factors, outside the control of an accused infringer, affect whether a particular displayed

image would distract a user from a primary interaction."

While Interval did not address the nonobtrusive/nondistraction factors separately from the disputed claim language in its original brief, it rejects the arguments in its response brief (311 [PDF]). Citing to Exxon Research and Haemonetics Corp. Interval responds that just becuase discerning the meaning of the claim is difficult doesn't mean the claim is indefinite. More importantly, Interval argues the specification provides the needed parameters when it provides "'in an unobtrusive manner that does not distract the user' refers to an

embodiment that uses the 'unused spatial capacity' of the display screen." In other words, the standard is one of not overlapping the primary display.

Let's take a look at a handful of the 15 disputed terms.

"selective display" terms

Defendants argue that image content to be displayed must come from a predetermined scheduling information, i.e., you can't choose from that which does not exist. Interval argues that the "predetermined scheduling information" limitation only exists in dependent claims as a further embodiment and is not an implied limitation on the independent claims ('652 patent, claims 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 11, and '314 patent, claims 1, 3, 7, 10 and 13).

"image generated from a set of content data"

The disagreement here is with the Defendants' assertion that the output must be "defined by a content provider." The Defendants point to the specification of the '652 patent which states: "Each set of content data is formulated by a content provider and made available by a corresponding content providing system for use with the attention manager.” The Defendants also argue that this limitation goes to the very purpose of the patents, i.e., "afford[ing] an opportunity to content providers to

disseminate their information.” Defendants' position is that to ignore this limitation would provide an interpretation for the claims that exceeds the specification.

Interval again argues that Defendants' added language overlays an embodiment on the claims thus improperly limiting the claims. While Interval concedes that the content does come from content providers, that does not mean that the invention cannot manipulate and display that information in a manner other than that of the content provider.

"primary interaction"

This disagreement arises over what is not part of the primary interaction. Interval points to the introductory claim language: "A system for engaging the peripheral attention of [the user]." Defendants ignore this definition from the claim language and refer instead to language from the specification: "other

than operation that is part of the

attention manager according to the

invention." Defendants' argue that these two definitions are not consistent and that the definition extracted from the claim exceeds the scope of the definition taken from the specification.

“each content provider provides its content data to [a/the] content display

system independently of each other content provider”

Here the dispute is over what it means to "provide ... independently. Interval argues that that to provide independently means selecting the content to be provided without influence from other parties. Defendants argue it goes to the means for transmitting the information; in other words the content must come directly from the content provider and not through some other party. Interval points out that the limitation suggested by Defendants was specifically removed during the original prosecution of the patent.

These are not minor disagreements. They could dramatically alter the scope of the claims and, as a consequence, whether the claims have been infringed.

In two separate matters the Court has sided with Interval with respect to its motion to incorporate Apple's OS X into the complaint. (see, Interval Moves to Incorporate Mountain Lion) Second, the Court granted the Defendants' motion to compel (281 [PDF]) with respect to again producing Interval's expert witness for deposition.

***************

Docket

272 - Filed: 08/15/2012 -

APPLICATION OF ATTORNEY Matthew Behncke FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR PRO HAC VICE for Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC (Fee Paid) Receipt No. 0981-2914063. (Berry, Matthew) (Entered: 08/15/2012)

273 - Filed: 08/16/2012 -

ORDER re (272 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP) Application for Leave to Appear Pro Hac Vice. The Court ADMITS Attorney Matthew Behncke for Interval Licensing LLC, by William M. McCool. (No document associated with this docket entry, text only.)(DS) (Entered: 08/16/2012)

274 - Filed: 08/22/2012 -

FILED IN ERROR, ATTY WILL REFILE MOTION. MOTION for Leave to Amend its Supplemental Infringement Contentions by Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Declaration of Nick P. Patel, # 2 Exhibit A, # 3 Exhibit B, # 4 Exhibit C, # 5 Exhibit D, # 6 Exhibit E, # 7 Exhibit F, # 8 Proposed Order)(Patel, Niraj) Modified text on 8/23/2012 (CL). (Entered: 08/22/2012)

08/23/2012

Filed: 8/23/2012 - Noting Date Set/Reset re (274 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP) MOTION for Leave to Amend its Supplemental Infringement Contentions : Noting Date 9/7/2012, (IM) (Entered: 08/23/2012)

Filed: 08/23/2012 -

***Motion terminated: 274 MOTION for Leave to Amend its Supplemental Infringement Contentions filed by Interval Licensing LLC. (Per filing atty, motion filed in error, will refile motion) (CL) (Entered: 08/23/2012)

275 - Filed: 08/23/2012 -

MOTION for Leave to Amend its Supplemental Infringement Contentions by Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Declaration of Nick P. Patel, # 2 Exhibit A, # 3 Exhibit B, # 4 Exhibit C, # 5 Exhibit D, # 6 Exhibit E, # 7 Exhibit F, # 8 Proposed Order) Noting Date 9/7/2012, (Patel, Niraj) (Entered: 08/23/2012)

276 - Filed: 09/04/2012 -

STATEMENT re 275 MOTION for Leave to Amend its Supplemental Infringement Contentions by Defendant Apple Inc. (Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 09/04/2012)

277 - Filed: 09/14/2012 -

STATEMENT re Joint Claim Construction and Prehearing Statement by Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit A - '652 Patent, # 2 Exhibit B - '314 Patent, # 3 Exhibit C1 - '652 Intrinsic Evidence, # 4 Exhibit D1 - '314 Intrinsic Evidence, # 5 Exhibit 1 - Joint Claim Chart, # 6 Exhibit 2 - Interval's Infringement Contentions, # 7 Exhibit 3 - Defendants' Invalidity Contentions)(Wilson, Douglas) (Entered: 09/14/2012)

278 - Filed: 09/17/2012 -

APPLICATION OF ATTORNEY James E. Eakin FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR PRO HAC VICE for Interested Parties Golan Levin, Paul Freiberger, Philippe Piernot (Fee Paid) Receipt No. 0981-2948604. (Thomas, Jeffrey) (Entered: 09/17/2012)

279 - Filed: 09/17/2012 -

NOTICE of Appearance by attorney Jeffrey I Tilden on behalf of Interested Parties Paul Freiberger, Golan Levin, Philippe Piernot. (Tilden, Jeffrey) (Entered: 09/17/2012)

280 - Filed: 09/18/2012 -

ORDER re (278 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP) Application for Leave to Appear Pro Hac Vice. The Court ADMITS Attorney James E. Eakin for Paul Freiberger, Golan Levin, and for Philippe Piernot, by William M. McCool. (No document associated with this docket entry, text only.)(DS) (Entered: 09/18/2012)

281 - Filed: 09/20/2012 -

Joint MOTION to Compel LR 37 Submission Re Expert Deposition by Defendant Google Inc. Noting Date 9/20/2012, (Jost, Shannon) (Entered: 09/20/2012)

282 - Filed: 09/20/2012 -

DECLARATION of Shannon M. Jost filed by Defendants Google Inc, Google Inc re (281 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP, 34 in 2:11-cv-00711-MJP, 32 in 2:11-cv-00716-MJP, 33 in 2:11-cv-00708-MJP) Joint MOTION to Compel LR 37 Submission Re Expert Deposition (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit, # 2 Proposed Order)(Jost, Shannon) (Entered: 09/20/2012)

283 - Filed: 09/20/2012 -

DECLARATION of Douglas Wilson filed by Defendants Google Inc, Google Inc re (281 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP, 34 in 2:11-cv-00711-MJP, 32 in 2:11-cv-00716-MJP, 33 in 2:11-cv-00708-MJP) Joint MOTION to Compel LR 37 Submission Re Expert Deposition (Jost, Shannon) (Entered: 09/20/2012)

284 - Filed: 09/24/2012 -

MOTION for Leave to Amend Their Invalidity Contentions by Defendant Apple Inc. (Attachments: # 1 Proposed Order) Noting Date 10/12/2012, (Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 09/24/2012)

285 - Filed: 09/24/2012 -

DECLARATION of Mark Liang filed by Defendant Apple Inc re 284 MOTION for Leave to Amend Their Invalidity Contentions (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit Exhs A - C, # 2 Exhibit Exhs D - G1, # 3Exhibit Exhs G2 - I1, # 4 Exhibit Exhs I2 - J)(Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 09/24/2012)

286 - Filed: 09/24/2012 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE by Defendant Apple Inc re 284 MOTION for Leave to Amend Their Invalidity Contentions . (Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 09/24/2012)

287 - Filed: 09/27/2012 -

APPLICATION OF ATTORNEY Robert A. Bullwinkel FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR PRO HAC VICE for Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC (Fee Paid) Receipt No. 0981-2961374. (Berry, Matthew) (Entered: 09/27/2012)

288 - Filed: 09/27/2012 -

ORDER re (287 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP) Application for Leave to Appear Pro Hac Vice. The Court ADMITS Attorney Robert A. Bullwinkel for Interval Licensing LLC, by William M. McCool. (No document associated with this docket entry, text only.)(DS) (Entered: 09/27/2012)

289 - Filed: 09/27/2012 -

ORDER granting (275)Plaintiff's Motion for Leave to amend it's Supplemental Infringement Contentions in case 2:10-cv-01385-MJP; granting (29) Motion for Leave in case 2:11-cv-00708-MJP, by Judge Marsha J. Pechman. (Order filed in both C10-1385MJP and related case C11-708MJP)(MD) (Entered: 09/27/2012)

290 - Filed: 09/27/2012 -

ORDER on LR 37 submission - granting (281) Joint Motion to Compel in case 2:10-cv-01385-MJP; granting (33) Motion to Compel in case 2:11-cv-00708-MJP; granting (34) Motion to Compel in case 2:11-cv-00711-MJP; granting (32) Motion to Compel in case 2:11-cv-00716-MJP, by Judge Marsha J. Pechman. (Order Posted in Lead and related cases C10-1385MJP, C11-708MJP, C11-711MJP, C11-716MJP)(MD) (Entered: 09/28/2012)

291 - Filed: 10/01/2012 -

MOTION Joint Request to Adjust Claim Construction Briefing Schedule by Defendant Google Inc. (Attachments: # 1 Proposed Order) Noting Date 10/1/2012, (Jost, Shannon) (Entered: 10/01/2012)

292 - Filed: 10/03/2012 -

ORDER granting (291) Joint Motion to adjust Claim Construction Briefing Schedule (Track 314-652) in case 2:10-cv-01385-MJP. Opening claim construction briefs due 10/9/2012, by Judge Marsha J. Pechman. (Order posted in Case Numbers C10-1385MJP, C11-708MJP, C11-711MJP and C11-716MJP)(MD) (Entered: 10/04/2012)

293 - Filed: 10/08/2012 -

RESPONSE, by Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC, to 284 MOTION for Leave to Amend Their Invalidity Contentions. Oral Argument Requested. (Attachments: # 1 Declaration of Nick Patel, # 2Exhibit A, # 3 Exhibit B, # 4 Exhibit C, # 5 Exhibit D, # 6 Exhibit E, # 7 Exhibit F, # 8 Proposed Order)(Patel, Niraj) (Entered: 10/08/2012)

294 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

MOTION for Protective Order Tri-Party Rule 37 Submission by Defendant AOL Inc, Interested Parties Paul Freiberger, Golan Levin, Philippe Piernot, Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Proposed Order) Noting Date 10/9/2012, (Thomas, Jeffrey) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

295 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

DECLARATION of James E. Eakin filed by Defendant AOL Inc, Interested Parties Paul Freiberger, Golan Levin, Philippe Piernot, Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC re 294 MOTION for Protective Order Tri-Party Rule 37 Submission (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit Exs A-G and K)(Thomas, Jeffrey) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

296 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

DECLARATION of Mark P. Walters filed by Defendant AOL Inc, Interested Parties Paul Freiberger, Golan Levin, Philippe Piernot, Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC re 294 MOTION for Protective Order Tri-Party Rule 37 Submission (Thomas, Jeffrey) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

297 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

DECLARATION of Matthew Berry filed by Defendant AOL Inc, Interested Parties Paul Freiberger, Golan Levin, Philippe Piernot, Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC re 294 MOTION for Protective Order Tri-Party Rule 37 Submission (Thomas, Jeffrey) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

298 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

DECLARATION of Cortney S. Alexander filed by Defendant AOL Inc, Interested Parties Paul Freiberger, Golan Levin, Philippe Piernot, Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC re 294 MOTION for Protective Order Tri-Party Rule 37 Submission (Thomas, Jeffrey) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

299 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE by Defendant AOL Inc, Interested Parties Paul Freiberger, Golan Levin, Philippe Piernot, Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC re 295 Declaration, 296 Declaration, 298Declaration, 294 MOTION for Protective Order Tri-Party Rule 37 Submission, 297 Declaration, . (Thomas, Jeffrey) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

300 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

OPENING BRIEF Local Patent Rule 134(a) Opening Claim Construction Brief ('652 and '314 Patents Track) by Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC. (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit AExhibit B, # 3 Exhibit C)(Davis, Nathan) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

301 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

OPENING BRIEF Defendants' Opening Brief in Support of Proposed Claim Constructions ('652/'314 Track) by Defendant Google Inc. (Jost, Shannon) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

302 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

DECLARATION of Shannon M. Jost of Shannon M. Jost re (301 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP) Brief - Opening by Defendant Google Inc. (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit A, # 2 Exhibit B, # 3 Exhibit C, # 4 Exhibit D, # 5 Exhibit E, # 6 Exhibit F, # 7 Exhibit G, # 8 Exhibit H)(Jost, Shannon) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

303 - Filed: 10/09/2012 -

DECLARATION of Bruce Maggs re (301 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP) Brief - Opening by Defendant Google Inc. (Jost, Shannon) (Entered: 10/09/2012)

304 - Filed: 10/12/2012 -

MINUTE ENTRY for proceedings held before Judge Marsha J. Pechman- Dep Clerk: Rhonda Miller; Pla Counsel: Matthew Berry, Justin Nelson, Davina Inslee; Def Counsel: Cortney Alexander, Molly Terwilliger, Mark Walters; and James Eakin CR: Danae Hovland; Motion Hearing held on 10/12/2012 regarding 294 MOTION for Protective Order Tri-Party Rule 37 Submission filed by Paul Freiberger, Philippe Piernot, Interval Licensing LLC, Golan Levin, AOL Inc. Oral argument. Court denies motion for the reasons stated on the record. (RM) (Entered: 10/12/2012)

305 - Filed: 10/12/2012 -

REPLY, filed by Defendant Apple Inc, TO RESPONSE to 284 MOTION for Leave to Amend Their Invalidity Contentions (Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 10/12/2012)

306 - Filed: 10/12/2012 -

DECLARATION of Mark Liang filed by Defendant Apple Inc re 284 MOTION for Leave to Amend Their Invalidity Contentions (Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 10/12/2012)

307 - Filed: 10/12/2012 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE by Defendant Apple Inc re Defs' Reply in Support of Their Motion for Leave to Amend Their Invalidity Contentions. (Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 10/12/2012)

308 - Filed: 10/22/2012 -

APPLICATION OF ATTORNEY Mark Liang FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR PRO HAC VICE for Defendant Apple Inc (Fee Paid) Receipt No. 0981-2989545. (Attachments: # 1 ECF Registration Form)(Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 10/22/2012)

309 - Filed: 10/22/2012 -

NOTICE OF WITHDRAWAL OF COUNSEL: Attorney Neil L. Yang for Defendant Apple Inc. (Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 10/22/2012)

310 - Filed: 10/23/2012 -

ORDER re (308 in 2:10-cv-01385-MJP) Application for Leave to Appear Pro Hac Vice. The Court ADMITS Attorney Mark Liang for Apple Inc, by William M. McCool. (No document associated with this docket entry, text only.)(DS) (Entered: 10/23/2012)

311 - Filed: 10/26/2012 -

RESPONSIVE BRIEF Interval's Responsive Claim Construction Brief ('652 and '314 Patents Track) by Plaintiff Interval Licensing LLC.. (Attachments: # 1 Declaration, # 2 Exhibit A, # 3 Exhibit B, # 4 Exhibit C, # 5 Exhibit D, # 6 Exhibit E, # 7 Exhibit F)(Davis, Nathan) (Entered: 10/26/2012)

312 - Filed: 10/26/2012 -

NOTICE of Association of Attorney by Jeremy E Roller on behalf of Defendant Apple Inc. (Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 10/26/2012)

313 - Filed: 10/26/2012 -

APPLICATION OF ATTORNEY David Alberti FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR PRO HAC VICE for Defendant Apple Inc (Fee Paid) Receipt No. 0981-2995830. (Attachments: # 1 ECF Registration)(Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 10/26/2012)

314 - Filed: 10/26/2012 -

APPLICATION OF ATTORNEY Yakov Zolotorev FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR PRO HAC VICE for Defendant Apple Inc (Fee Paid) Receipt No. 0981-2995836. (Attachments: # 1 ECF Registration)(Roller, Jeremy) (Entered: 10/26/2012)

315 - Filed: 10/26/2012 -

RESPONSE by Defendant Yahoo! Inc re 300 Brief - Opening Apple's, Google's, AOL's, and Yahoo!'s Responsive Claim Construction Brief ('652 and '314 Patents Track). (Attachments: # 1 Appendix)(Walters, Mark) (Entered: 10/26/2012)

316 - Filed: 10/26/2012 -

DECLARATION of Mark Walters in Support of Apple's, Google's, AOL's, and Yahoo!'s Responsive Claim Construction Brief ('652 and '314 Patents Track) re 315 Response (non motion), by Defendant Yahoo! Inc. (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit A)(Walters, Mark) (Entered: 10/26/2012)

***************

Documents

300

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON

AT SEATTLE

INTERVAL LICENSING LLC,

Plaintiff,

vs.

AOL, INC.; APPLE, INC.; GOOGLE, INC.;

AND YAHOO! INC.,

Defendants.

Case Nos. 2:10-cv-01385-MJP, 2:11-cv-

00708-MJP, 2:11-cv-00711-MJP, 2:11-cv-

00716-MJP

JURY TRIAL DEMANDED

PLAINTIFF INTERVAL LICENSING LLC’S LOCAL PATENT RULE 134(a)

OPENING CLAIM CONSTRUCTION BRIEF (’652 AND ’314 PATENTS TRACK)

Responsive Brief Due Date: October 26, 2012

TABLE OF CONTENTS

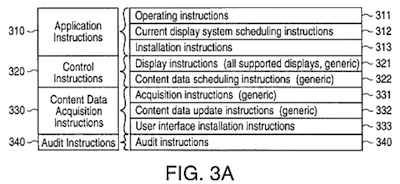

I. Introduction and Overview of the Patented Technology .............................................. 1

II. Relevant Law ..................................................................................................................... 1

III. Terms for Construction .................................................................................................... 4

1. “selective display” terms ......................................................................................... 4

2. “images generated from a set of content data” ..................................................... 7

3. “in an unobtrusive manner that does not distract a user of the apparatus from

a primary interaction with the apparatus” ........................................................... 8

4. “primary interaction” ............................................................................................ 15

5. “means for selectively displaying on the display device, in an unobtrusive

manner that does not distract a user of the apparatus from a primary

interaction with the apparatus, an image or images generated from the set of

content data” .......................................................................................................... 16

6. “each content provider provides its content data to [a/the] content display

system independently of each other content provider” ...................................... 19

7. “user interface installation instructions for enabling provision of a user

interface that allows a person to request the set of content data from the

specified information source” ............................................................................... 20

8. “during operation of an attention manager”....................................................... 22

9. “means for acquiring a set of content data from a content providing system” 23

10. “content provider” ................................................................................................. 26

11. “content data scheduling instructions for providing temporal constraints on

the display of the image or images generated from the set of content data” .... 28

12. “content data update instructions for enabling acquisition of an updated set of

content data from an information source that corresponds to a previously

acquired set of content data” ................................................................................ 30

13. “content display system scheduling instructions for scheduling the display of

the image or images on the display device” ......................................................... 30

14. “instructions” ......................................................................................................... 32

15. “means for displaying one or more control options with the display device

while the means for selectively displaying is operating” .................................... 35

IV. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................... 38

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Adams Respiratory Therapeutics, Inc. v. Perrigo Co.,

616 F.3d 1283 (Fed. Cir. 2010)..................................................................................................... 31

Arlington Indus., Inc. v. Bridgeport Fittings, Inc.,

632 F.3d 1246 (Fed. Cir. 2011)....................................................................................................... 3

Asyst Techs., Inc. v. Empak, Inc.,

268 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2001)....................................................................................................... 4

Aventis Pharma S.A. v. Hospira, Inc.,

675 F.3d 1324 (Fed. Cir. 2012)..................................................................................................... 10

Baden Sports, Inc. v. Molten, No. C06-0210,

2007 WL 1847246, (W.D. Wash. Jun. 26, 2007) ........................................................................... 3

Boss Control, Inc. v. Bombardier Inc.,

410 F.3d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2005)..................................................................................................... 10

Brown v. 3M,

265 F.3d 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2001)) ..................................................................................................... 2

Corning Glass Works v. Sumitomo Elec. U.S.A., Inc.,

868 F.2d 1251 (Fed. Cir. 1989)....................................................................................................... 1

Dealertrack, Inc. v. Huber,

674 F.3d 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2012)..................................................................................................... 37

Dentx Prods., LLC v. Advantage Dental Prods., Inc.,

309 F.3d 774 (Fed. Cir. 2002)....................................................................................................... 14

Energizer Holdings, Inc. v. Int’l Trade Comm’n,

435 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2006)..................................................................................................... 13

Exxon Res. & Eng’g Co. v. United States,

265 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2001)..................................................................................................... 13

Finisar Corp. v. DirecTV Grp., Inc.,

523 F.3d 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2008)..................................................................................................... 38

Honeywell Int’l, Inc. v. Universal Avionics Sys. Corp.,

493 F.3d 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2007)....................................................................................................... 2

Immunocept, LLC v. Fulbright & Jaworski, LLP,

ii

504 F.3d 1281 (Fed. Cir. 2007)..................................................................................................... 15

In re Suitco Surface, Inc.,

603 F.3d 1255 (Fed. Cir. 2010)..................................................................................................... 11

In re Yamamoto,

740 F.2d 1569 (Fed. Cir. 1984)..................................................................................................... 11

Kinetic Concepts, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc.,

688 F.3d 1342 (Fed. Cir. 2012)..................................................................................................... 12

Krippelz v. Ford Motor Co.,

667 F.3d 1261 (Fed. Cir. 2012)..................................................................................................... 12

Liebel-Flarsheim Co. v. Medrad, Inc.,

358 F.3d 898 (Fed. Cir. 2004)......................................................................................................... 3

Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc.,

517 U.S. 370 (1996) ........................................................................................................................ 2

Martek Biosciences Corp. v. Nutrinova, Inc.,

579 F.3d 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2009)....................................................................................................... 3

Micro Chem., Inc. v. Great Plains Chem. Co., Inc.,

194 F.3d 1250 (Fed. Cir. 1999)....................................................................................................... 4

Noah Systems, Inc. v. Intuit Inc.,

675 F.3d 1302 (Fed. Cir. 2012)..................................................................................................... 36

Phillips v. AWH Corp.,

415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005).............................................................................................. passim

Power-One, Inc. v. Artesyn Techs., Inc.,

599 F.3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2010)..................................................................................................... 14

Praxair, Inc. v. ATMI, Inc.,

543 F.3d 1306 (Fed. Cir. 2008)..................................................................................................... 13

Silicon Graphics, Inc. v. ATI Techs., Inc.,

607 F.3d 784 (Fed. Cir. 2010)......................................................................................................... 8

Spectrum Int’l, Inc. v. Sterilite Corp.,

164 F.3d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 1998)..................................................................................................... 10

SuperGuide Corp. v. DirecTV Enterprises, Inc.,

358 F.3d 870 (Fed. Cir. 2004)......................................................................................................... 3

iii

Thorner v. Sony Comp. Entm’t. Am. LLC,

669 F.3d 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2012)..................................................................................................... 15

Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc.,

90 F.3d 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1996)......................................................................................................... 6

Statutes

35 U.S.C. §112, ¶ 6 ................................................................................................................... 4, 36

Other Authorities

The IEEE Standard Dictionary of Electrical and Electronics Terms (6th Ed.) ............................. 32

Webster’s New World College Dictionary, 4th ed. (2010) ........................................................... 19

iv

Pursuant to Local Patent Rule 134 and the Court’s Scheduling Order (Docket No. 271),

Interval Licensing LLC (“Interval”) submits this Opening Brief on Claim Construction. In

accordance with the Court’s Scheduling Order, the parties have identified for construction 15

terms for U.S. Patent Nos. 6,034,652 (“the ’652 patent”) and 6,788,314 (“the ’314 patent”).

I. Introduction and Overview of the Patented Technology

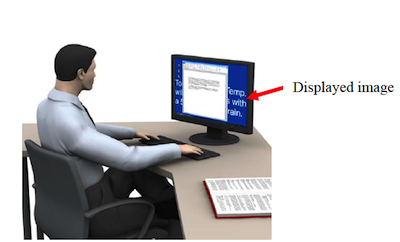

The two patents asserted in the present litigation are directed to inventions developed at

Interval Research Corporation, a private research company founded by Paul Allen and David

Liddle in the early 1990s. The rapid development of the Internet in the 1990s made an enormous

quantity of information available to the public. The inventions described in the ’652 and ’314

patents were aimed at helping users navigate and use this massive universe of information more

quickly and easily. They accomplish this by providing information to a user in non-distracting

ways that do not interfere with the user’s primary activity on a device such as a computer. In this

manner, the inventions improve users’ ability to take advantage of available information by

allowing for the flow of other sources of information that they otherwise would not see.

The primary flaw with most of the Defendants’ proposed constructions is that over and

over again, they attempt to add language to the definition in an attempt to create ambiguity and

unnecessarily change the scope of the claims in ways unsupported by the specification and claim

language.

II. Relevant Law

“A claim in a patent provides the metes and bounds of the right which the patent confers

on the patentee to exclude others from making, using, or selling the protected invention.”

Corning Glass Works v. Sumitomo Elec. U.S.A., Inc., 868 F.2d 1251, 1257 (Fed. Cir. 1989). The

1

construction of terms used in a patent claim is a question of law. Markman v. Westview

Instruments, Inc., 517 U.S. 370, 391 (1996).

Claims are to be construed from the perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art of

the field of the patented invention at the time of the effective filing date of the patent application.

Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc). In cases of nontechnical

words with ordinary meanings that are readily apparent, “elaborate interpretation” is

not required. Id. at 1314 (citing Brown v. 3M, 265 F.3d 1349, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2001)).1 When

such an ordinary meaning is not apparent, the courts look to the language of the claims, the

specification, prosecution history, and extrinsic evidence such as dictionaries and treatises. Id. at

1314-18. The specification, including the claim language, “is always highly relevant to the claim

construction analysis. Usually, it is dispositive; it is the single best guide to the meaning of a

disputed term.” Id. at 1315. The patentee may in some cases act as his or her own

lexicographer. “When a patentee defines a claim term, the patentee’s definition governs, even if

it is contrary to the conventional meaning of the term.” Honeywell Int’l, Inc. v. Universal

Avionics Sys. Corp., 493 F.3d 1358, 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2007). The prosecution history may also be

helpful. Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1317. However, “it often lacks the clarity of the specification and

thus is less useful for claim construction purposes.” Id. Extrinsic evidence may provide guidance

in some circumstances, but should not be used to “change the meaning of the claims in

___________________________

1 See also Peter S. Menell, Matthew D. Powers & Steven C. Carlson, Patent Claim Construction:

A Modern Synthesis and Structured Framework, 25 Berkeley Tech. Law J. 711, 732 (2010) (“For

many claim terms, attempting to ‘construe’ the claim language adds little in the way of clarity.

Where the perspective of a person having ordinary skill in the art would add nothing to the

analysis, there may be no need to construe the terms. . . . Where ‘construing’ a claim term would

involve simply substituting a synonym for the claim term, it may be appropriate to allow the

claim language to speak for itself.”).

2

derogation of the indisputable public records consisting of the claims, the specification and the

prosecution history . . .” Id. at 1319 (quotation marks omitted).

Features of a preferred embodiment must not be read into the claims as new limitations

unless the patentee expressed a clear intent to do so. Liebel-Flarsheim Co. v. Medrad, Inc., 358

F.3d 898, 906-08 (Fed. Cir. 2004); SuperGuide Corp. v. DirecTV Enterprises, Inc., 358 F.3d

870, 880 (Fed. Cir. 2004). In fact, the Federal Circuit cautioned in its oft-cited Phillips opinion

that “although the specification often describes very specific embodiments of the invention, we

have repeatedly warned against confining the claims to those embodiments.” Phillips, 415 F.3d

at 1323. Even today, the Federal Circuit continues to correct district courts that confine claim

scope to embodiments disclosed in the specification despite the lack of the patentee’s intent to do

so. Arlington Indus., Inc. v. Bridgeport Fittings, Inc., 632 F.3d 1246, 1254 (Fed. Cir. 2011)

(“[E]ven where a patent describes only a single embodiment, claims will not be read restrictively

unless the patentee has demonstrated a clear intention to limit the claim scope using words of

expressions of manifest exclusion or restriction.”) (quoting Martek Biosciences Corp. v.

Nutrinova, Inc., 579 F.3d 1363, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (reversing a district court that made a

similar error of limiting claim scope to a particular embodiment in the absence of limiting claim

language)). This Court’s previous rulings have been consistent with Federal Circuit precedent.

E.g., Baden Sports, Inc. v. Molten, No. C06-0210, 2007 WL 1847246, at *2 (W.D. Wash. Jun.

26, 2007) (Pechman, J.) (“Although a court should limit the meaning of a claim where the

‘specification makes clear that the invention does not include a particular feature,’ the court must

not read ‘particular embodiments and examples appearing in the specification’ into the claims

unless the specification requires it.”).

3

Section 112, ¶ 6 of the Patent Act permits claim limitations that “express[] a means or

step for performing a specified function without . . . recit[ing] structure, material, or acts in

support thereof.” These types of limitations, often referred to as “means-plus-function”

limitations, “shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described

in the specification and equivalents thereof.” 35 U.S.C. §112, ¶ 6.

Construing a means-plus-function limitation is a two-step process. Asyst Techs., Inc. v.

Empak, Inc., 268 F.3d 1364, 1369 (Fed. Cir. 2001). First, the court must “identify the function

explicitly recited in the claim.” Id. The second step is to “identify the corresponding structure

set forth in the written description that performs the particular function set forth in the claim.”

Id. at 1369-70. The identified structure must not include “structure from the written description

beyond that necessary to perform the claimed function.” Micro Chem., Inc. v. Great Plains

Chem. Co., Inc., 194 F.3d 1250, 1258 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

III. Terms for Construction2

As set forth in Exhibit A, the parties have agreed to constructions for eight terms. The

parties continue to dispute the constructions of the 15 terms identified and discussed below. For

the reasons set forth herein, Interval respectfully requests that the Court adopt Interval’s

proposed constructions and reject those proposed by Defendants.

1. “selective display” terms

| Claim Language | Interval's Proposed

| Defendants' Proposed

Construction |

“selectively displaying on the

display device . . . an image or | [choose/choosing] and

display[ing] one or more | [choose/choosing] and

display[ing] one or more |

___________________________

2 The ’652 and ’314 patents are related and share a common specification. For convenience and

brevity, citations will be provided to the ’652 patent specification. The cited passages also

appear in the ’314 patent, although the column and line numbers may not correspond exactly.

4

images generated from the set of

content data”

(’652 claim 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11 and

’314 claims 10 and 13)

“selectively display. . . an image

or images generated from a set of

content data”

(’314 claim 1 and 3)

“selective display on the display

device. . . of an image or images

generated from the set of content

data”

(’314 claim 7) | “images generated from the set

of content data” | “images generated from

the set of content data”

according to

predetermined scheduling

information |

The parties agree that selectively displaying an image or images on the display device

entails “[choose/choosing] and display[ing] one or more ‘images generated from the set of

content data.’” Defendants, however, seek to further limit selectively displaying to only occur

“according to predetermined scheduling information.” Defendants’ proposal cannot be

reconciled with dependent claims that expressly add scheduling limitations and introduces

unnecessary ambiguity about the meaning of “predetermined” that Defendants presumably

intend to rely upon in front of the jury in a manner that would exclude preferred embodiments

and conflict with the prosecution history.

Claim 4 of the ’652 patent is representative and comprises a “means for selectively

displaying on the display device . . . an image or images generated from the set of content

data . . . .” ’652 patent at 30:29-33. The plain language of the claim does not require selection in

accordance with scheduling information (either “predetermined” or otherwise). Although certain

embodiments include scheduling, such functionality should not be imported into claims in the

absence of a specific limitation. See Kara Tech. Inc. v. Stamps.com Inc., 582 F.3d 1341, 1348

5

(Fed. Cir. 2009) (“The claims, not specification embodiments, define the scope of patent

protection. The patentee is entitled to the full scope of his claims, and we will not limit him to his

preferred embodiment or import a limitation from the specification into the claims.”). Moreover,

claims 6-10, which depend from claim 4, do contain limitations directed to scheduling: “the

means for selectively displaying further comprises means for scheduling the display of an image

or images generated from a set of content data . . . .” Id. at 30:46-48 (emphasis added). Thus,

this limitation should not be imported into the construction of “selectively displaying” found in

the independent claims. See Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1315 (“[T]he presence of a dependent claim

that adds a particular limitation gives rise to a presumption that the limitation in question is not

present in the independent claim.”).

Defendants’ proposed “predetermination” requirement also introduces unwarranted

ambiguity and invites interpretations that would be clearly incorrect under principles of claim

construction. Defendants’ proposed addition leaves undetermined the event with respect to

which the scheduling information must be “predetermined.” If interpreted to mean before the

system begins operating or before content data is acquired, that interpretation would exclude one

of the preferred embodiments, which determines the schedule after “one or more sets of content

data ha[ve] been acquired.” See ’652 patent at 2:28-34, 10:4-8; see also Vitronics Corp. v.

Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (an interpretation that excludes a

preferred embodiment is “rarely, if ever, correct”). And if the triggering event is the display of

the first image generated from the first set of content data, such an interpretation would exclude

another preferred embodiment that permits the display schedule to be re-determined at any time.

See ’652 patent at 12:38-42. Indeed, this embodiment that permits the display schedule to be

changed at any time is directly contrary to Defendants’ proposed “predetermined schedule”

6

requirement. As the applicant emphasized during the original prosecution, the claimed invention

can provide a “flexible and varied display.” ’652 patent file history, 7/3/1998 Response to

Office Action, at 9 (IL_DEFTS0007923). A vague requirement that the display schedule must

be “predetermined” invites improper arguments that are wholly inconsistent with the claimed

invention, the specification, and the claims.

2. “images generated from a set of content data”

| Claim Language | Interval's Proposed Construction | Defendants' Proposed Construction |

“images generated

from a set of content

data”

(All Claims) | audio and/or visual output that is

generated from data within a set of

related data | audio and/or visual output defined

by a content provider that is

generated from data within a set of

related data |

The only dispute between the parties with respect to this term is whether the audio and/or

visual output must be “defined by a content provider,” as Defendants propose. This additional

limitation is improper for two reasons. First, the specification provides definitions for both

“image” and “content data,” and neither definition requires that the output be “defined by a

content provider”:

- “The term ‘image’ is used broadly here to mean any sensory stimulus that is produced

from the set of content data, including, for example, visual imagery (e.g., moving or still

pictures, text, or numerical information) and audio imagery (i.e., sounds).” ’652 patent

at 6:60-64 (emphasis added).

- “Herein, ‘content data’ refers to data that is used by the attention manager to generate

displays (e.g., video images or sounds, or related sequences of video images or sounds).”

’652 patent at 9:51-54.

These definitions expressly encompass “any” output produced from data within the set of content

data and therefore leave no room for an additional limitation restricting the claimed output to

only such output that was “defined by the content provider.” See Silicon Graphics, Inc. v. ATI

7

Techs., Inc., 607 F.3d 784, 789 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (“If the specification reveals a special definition

for a claim term, ‘the inventor’s lexicography governs.’” (quoting Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1316)).

Second, Defendants’ proposed construction also introduces unnecessary ambiguity about

what it means for the output to be “defined by a content provider”—a concept that finds no

support in the specification. The purpose of the claim construction exercise is for the Court to

identify the bounds of the claims. Introducing an amorphous new limiting concept that lacks any

basis in the specification hardly serves this function. To the extent Defendants intend to argue

that this limitation imposes a requirement that the content provider must take an active role in the

original creation of the content, that interpretation is incorrect for the reasons discussed below

with respect to the term “content provider.” See infra § III.10.

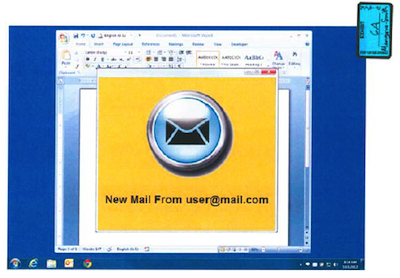

3. “in an unobtrusive manner that does not distract a user of the apparatus

from a primary interaction with the apparatus”

| Claim Language | Interval’s Proposed

Construction |

Defendants’ Proposed

Construction |

“in an unobtrusive manner that

does not distract a user of the

apparatus from a primary

interaction with the apparatus”

(’652 claim 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11)

“in an unobtrusive manner that

does not distract a user of the

display device or an apparatus

associated with the display device

from a primary interaction with

the display device or apparatus”

(’314 all asserted claims (via

claims 1, 3, 7, 10 and 13)) |

during a user’s primary

interaction with the apparatus

and unobtrusively such that

the images generated from the

set of content data are

displayed in addition to the

display of images resulting

from the user’s primary

interaction |

As written, this term is

inherently subjective and

therefore indefinite.

Alternatively, this must be

limited such that the images

are displayed either when

the attention manager [or

system] detects that the user

is not engaged in a primary

interaction or as a

background of the computer

screen |

Interval’s proposed construction of this term flows from the teaching of the specification,

including an express definition of what the patent means by the “unobtrusive manner” language

8

There are three primary disputes concerning this term: (1) whether the proper construction of this

term should encompass screensaver-type displays of information during idle times (i.e., after the

system detects that the user is not engaged in a primary interaction); (2) whether it is subjective

and indefinite; and (3) whether it is limited to displaying information “as a background of the

computer screen.” The answer to each question is “no.”

First, the proper construction does not encompass idle-time display of information such

as screensavers. The ’652 and ’314 patents teach ways to distribute information by engaging “at

least the peripheral attention” of a user of a device such as a computer. ’652 patent at Abstract.

The patents use “peripheral attention” as an umbrella term to refer to the part of the user’s

attention that is not occupied by the user’s primary interaction with the device.3 The

specification teaches that this “unused capacity” can be either “temporal” (i.e., at a time when the

user is not actively using the device) or “spatial” (i.e., while the user is actively using the device

but in an area of the display that is not used by the primary interaction). ’652 patent at 6:23-51.

Similarly, “attention manager” is a blanket term used to refer to a system that occupies the user’s

peripheral attention in either the temporal or spatial dimension.4 Id. at Abstract, 6:23-51. The

patents describe two preferred embodiments of the attention manager, one of which is directed to

the user’s peripheral attention in the temporal dimension and the other of which is directed to the

spatial dimension:

Generally, the attention manager makes use of “unused capacity” of the display

device. For example, the information can be presented to the person while the

_________________________

3 The parties’ agreed construction of “engaging the peripheral attention of a person in the vicinity

of a display device” reflects this. See Ex. A at 1 (“engaging a part of the user’s attention that is

not occupied by the user’s primary interaction with the apparatus”).

4 The construction of “attention manager” is disputed. See infra § III.8.

9

apparatus (e.g., computer) is operating, but during inactive periods (i.e., when a

user is not engaged in an intensive interaction with the apparatus). Or, the

information can be presented to the person during active periods (i.e., when a user

is engaged in an intensive interaction with the apparatus, but in an unobtrusive

manner that does not distract the user from the primary interaction with the

apparatus (e.g., the information is presented in areas of a display screen that are

not used by displayed information associated with the primary interaction with the

apparatus).

’652 patent at 2:7-19 (emphasis added); see also id. at 3:19-31, 6:34-51, 13:14-17. As this

passage makes clear, the “unobtrusive manner” language describes the second embodiment of

the attention manager (i.e., the preferred spatial dimension embodiment), but not the first (i.e.,

the preferred temporal dimension embodiment).5 Defendants’ “alternative construction,” which

expressly includes the temporal/idle-time display embodiment, is inconsistent with the clear

teaching of the specification.6 See Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1315 (noting that the specification “is the

single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term”).

________________________

5 The differences between the various embodiments are also reflected in the claims. Some

claims are directed to all types of “attention managers” (e.g., claims 13-18 of the ’652 patent),

other claims are directed only to attention managers that present information in an “unobtrusive

manner” (e.g., claims 4-12 of the ’652 patent and all asserted claims of the ’314 patent).

6 During prosecution, there was some confusion about the relationship between the screensaver

embodiment and the “unobtrusive manner” embodiment. See ’652 patent file history, 7/3/1998

Response to Office Action, at 13-14 (IL_DEFTS0007927); ’652 patent file history, 6/10/1999

Response to Office Action, at 16 (IL_DEFTS0008051). However, these statements should not

be given controlling weight because the prosecution history is subordinate to the clear teaching

of the specification. See Boss Control, Inc. v. Bombardier Inc., 410 F.3d 1372, 1378 (Fed. Cir.

2005) (“Neither the dictionary definition nor the prosecution history, however, overcomes the

particular meaning . . . clearly set forth in the specification.”); see also Aventis Pharma S.A. v.

Hospira, Inc., 675 F.3d 1324, 1331 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (“The prosecution history can offer insight

into the meaning of a particular claim term, but the ‘[c]laim language and the specification

generally carry greater weight.’”). Additionally, statements made during prosecution are most

often relied upon during the claim construction process to prevent patentees from narrowly

interpreting their claims before the examiner in order to gain allowance, only to broaden those

interpretations once in litigation. See, e.g., Spectrum Int’l, Inc. v. Sterilite Corp., 164 F.3d 1372,

1378 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (“[E]xplicit statements made by a patent applicant during prosecution to

distinguish a claimed invention over prior art may serve to narrow the scope of a claim.”). This concern is not present here, where the applicant took an overly broad interpretation of the

“unobtrusive manner” language in an Office Action response. Moreover, as discussed in further

detail below, any ambiguity in the prosecution history was conclusively resolved in the

reexaminations, where the Examiner expressly addressed the scope of the “unobtrusive manner”

limitation and found that it did not encompass screensaver embodiments. The reexamination is

part of the prosecution history, and thus, the prosecution history as a whole supports Interval’s

position here.

10

When Defendants moved to stay the case, one of their arguments was that “the intrinsic

record remains in flux” regarding whether the “unobtrusive manner” language covers the

screensaver embodiment. Dkt. No. 256, at 3. This issue thus became central to the

reexamination, where Defendants made exactly the same claim construction argument in an

attempt to expand the “unobtrusive manner” language to capture idle-time displays such as

screensavers.

The USPTO considered Defendants’ interpretation of “unobtrusive manner” and rejected

it even under the more lenient rule that the USPTO must apply the “broadest reasonable

construction” (which should be broader than the actual construction that would be applied during

litigation). See In re Suitco Surface, Inc., 603 F.3d 1255, 1259 (Fed. Cir. 2010); In re

Yamamoto, 740 F.2d 1569, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1984) (explaining that the USPTO “broadly interprets

claims during examination” to “reduc[e] the possibility that claims, finally allowed, will be given

broader scope than is justified.”). As explained by the USPTO Examiner during the

reexamination of the ’652 patent:

The ’652 patent specification discloses two embodiments wherein the attention

manager makes use of “unused capacity” of the display device. The first is the

“screensaver embodiment” wherein the information can be presented to a person

while the apparatus (e.g. computer) is operating, but during inactive periods (i.e.,

when a user is not engaged in an intensive interaction with the apparatus). (col.

2:8-12)

11

The second is the “wallpaper embodiment” wherein information can be presented

to the person during active periods (i.e. when a user is engaged in an intensive

interaction with the apparatus) but in an unobtrusive manner that does not distract

the user from the primary interaction with the device (e.g. the information is

presented in areas of a display screen that are not used by displayed information

associated with the primary interaction with the apparatus). (col. 2:12-18)

Independent claim 4 claims means for selectively displaying on the display device,

in an unobtrusive manner that does not distract a user of the apparatus from a

primary interaction with the apparatus, an image or images generated from the

set of content data in combination with the other limitations of the claim. As

such, the broadest reasonable interpretation of independent claim 4, in light of the

specification, excludes the screensaver embodiment because the claim language

“in an unobtrusive manner that does not distract a user of the apparatus from a

primary interaction with the apparatus” is consistently and repeatedly linked to

the ‘wallpaper embodiment’ and excludes the ‘screensaver embodiment’. (see

also col. 3:20-40, col. 6:34-52, and col. 13:10-15).”

’652 Reexamination, 10/14/2011 Office Action, at 8-9 (INT00020742-43). The Examiner

reached the same conclusion in the ’314 patent reexamination. See ’314 Reexamination,

10/14/2011 Action Closing Prosecution, at 9-10 (INT00021469-70) (“[I]t is agreed that the

totality of the specification evidence supports an argument that the broadest reasonable

interpretation of the claims, in light of the specification, excludes the ‘screensaver

embodiment.’”).

In other words, the USPTO concluded not just that Defendants’ proposed interpretation is

incorrect, but that it is not even a reasonable interpretation. Moreover, Interval’s explanation

that the “unobtrusive manner” language does not encompass idle-time displays such as

screensavers and the examiner’s agreement with that argument is now part of the intrinsic record

that informs the claim construction analysis. See Kinetic Concepts, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc.,

688 F.3d 1342, 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2012); Krippelz v. Ford Motor Co., 667 F.3d 1261, 1267 (Fed.

Cir. 2012). Accordingly, the intrinsic record is no longer “in flux,” as Defendants argued in

support of the stay. Dkt. No. 256, at 3. Instead, it strongly supports Interval’s proposed

12

construction. This Court should accept Interval’s definition and affirm the USPTO’s conclusion

that the claims that use the “unobtrusive manner,” “in light of the specification, exclude[] the

screensaver embodiment because the claim language ‘in an unobtrusive manner that does not

distract a user of the apparatus from a primary interaction with the apparatus’ is consistently

and repeatedly linked to the ‘wallpaper embodiment’ and excludes the ‘screensaver

embodiment.’” See ’652 Reexamination, 10/14/2011 Office Action, at 8-9 (INT00020742-43).

Second, this term is not indefinite. “A claim will be found indefinite only if it is

insolubly ambiguous, and no narrowing construction can properly be adopted.” Praxair, Inc. v.

ATMI, Inc., 543 F.3d 1306, 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (quotation marks omitted). “If the meaning of

the claim is discernible, even though the task may be formidable and the conclusion may be one

over which reasonable persons will disagree, [the Federal Circuit has] held the claim sufficiently

clear to avoid invalidity on indefiniteness grounds.” Exxon Res. & Eng’g Co. v. United States,

265 F.3d 1371, 1375 (Fed. Cir. 2001). “Claim definiteness is analyzed not in a vacuum, but

always in light of the teachings of the prior art and of the particular application disclosure as it

would be interpreted by one possessing the ordinary level of skill in the pertinent art.” Energizer

Holdings, Inc. v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 435 F.3d 1366, 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (quotation marks

omitted). “The definiteness inquiry focuses on whether those skilled in the art would understand

the scope of the claim when the claim is read in light of the rest of the specification.” Id.

(quotation marks omitted).

The “unobtrusive manner” language is not subjective and/or indefinite because the

specification provides a clear, objective definition of what it means:

According to another further aspect of the invention, the selective display of an

image or images occurs while the user is engaged in a primary interaction with

the apparatus, which primary interaction can result in the display of an image or

13

images in addition to the image or images generated from the set of content data

(“the wallpaper embodiment”).

’652 patent at 3:25-31 (emphasis added); see also id. at 2:17-19 (“e.g., the information is

presented in areas of a display screen that are not used by displayed information associated with

the primary interaction with the apparatus”). This definition is reflected in Interval’s proposed

construction. Because the patentee acted as its own lexicographer by providing an objective

definition of the “unobtrusive manner”-type of display, one of ordinary skill in the art would

understand the meaning of this term. See Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1321 (“[T]he specification acts as

a dictionary when it expressly defines terms used in the claims or when it defines terms by

implication.” (quotation marks omitted)). Accordingly, there is no ambiguity at all with respect

to this term—let alone sufficient ambiguity to meet the high standard necessary for

indefiniteness. See All Dental Prodx, LLC v. Advantage Dental Prods., Inc., 309 F.3d 774, 780

(Fed. Cir. 2002) (“Only after a thorough attempt to understand the meaning of a claim has failed

to resolve material ambiguities can one conclude that the claim is invalid for indefiniteness.”);

see also Power-One, Inc. v. Artesyn Techs., Inc., 599 F.3d 1343, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (“Claims

using relative terms . . . are insolubly ambiguous only if they provide no guidance to those skilled

in the art as to the scope of that requirement.” (emphasis added)).

Third, this express definition is broad enough to cover embodiments beyond those that

display information as part of the background of a computer screen. Defendants’ attempt to limit

the claims to a preferred embodiment—namely, display as part of the background wallpaper on a

computer screen—should be rejected. See Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1323 (“[A]lthough the

specification often describes very specific embodiments of the invention, we have repeatedly

warned against confining the claims to those embodiments.”). The patent specification has

14

defined this term. That definition is what Interval uses. This Court should reject Defendants’

attempts to add language to the definition beyond the definition in the specification.

4. “primary interaction”

| Claim Language | Interval’s Proposed Construction | Defendants’ Proposed Construction |

“primary interaction”

(’652 claims 4, 34

and 35; ’314 claims

1, 3, 7, 10, 13) |

any operation of the computer (or

other apparatus with which the user

is engaging in an interaction) other

than operation that is part of the

system for engaging the peripheral

attention of the user |

any operation of the computer (or

other apparatus with which the user

is engaging in an interaction) other

than operation that is part of the

attention manager according to the

invention |

Both parties’ proposed constructions originate from the definition of “primary

interaction” that is set forth in the specification. See ’652 patent at 8:14-18. The only point of

dispute is whether the part of the system that implements the claimed invention should be

referred to in the construction as “the system for engaging the peripheral attention of the user”

(Interval’s position, which is derived from the preamble of the claims in which this limitation

appears) or “the attention manager according to the invention” (Defendants’ position, which is

taken verbatim from the specification). The blind adherence to the specification text proposed

by Defendants would improperly ask the jury to determine the meaning of “according to the

invention” and introduce other unnecessary confusion.

First, the claims define the scope of the invention. Thorner v. Sony Comp. Entm’t. Am.

LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2012). Accordingly, it makes no sense to define one

limitation—which is part of the definition of the claimed invention—with the term “according to

the invention.” Additionally, the determination of claim scope is a legal question of claim

construction reserved for the Court. Immunocept, LLC v. Fulbright & Jaworski, LLP, 504 F.3d

1281, 1285 (Fed. Cir. 2007). If Defendants’ construction were adopted, the jury would be

instructed at trial that the claims define the scope of the invention and they must apply the

15

Court’s constructions, only to be given a construction that requires them to determine the

meaning of “the invention.”

Second, none of the claims that contain the term “primary interaction” include the term

“attention manager.” The result is that under Defendants’ approach, the jury will be given a

confusing construction that refers to “the attention manager” for claims that do not recite an

attention manager. The likelihood for confusion is increased by the fact that other asserted

claims do recite an “attention manager,” and the construction of that term is separately disputed.

See ’652 Patent, Claims 15-18; infra § III.8.

Interval’s proposed construction avoids all of the problems with Defendants’ proposal by

simply replacing the reference to “the attention manager according to the invention” with

synonymous language that is used in the preamble of each claim (i.e., “the system for engaging

the peripheral attention of the user”). This substitution is entirely consistent with the

specification, as it replaces the out-of-context language of the specification with the language

from the claims. And as discussed in further detail below, Interval’s phraseology flows directly

from the definition of “attention manager” in the specification. See § III.8; ’652 patent at

Abstract.

5. “means for selectively displaying on the display device, in an unobtrusive

manner that does not distract a user of the apparatus from a primary

interaction with the apparatus, an image or images generated from the set of

content data”

| Claim Language | Interval’s Proposed Construction | Defendants’ Proposed Construction |

| means for

selectively

displaying on the

display device, in

an unobtrusive

manner that does

not distract a user |

FUNCTION: Selectively

displaying on the display device,

in an unobtrusive manner that

does not distract a user of the

apparatus from a primary

interaction with the apparatus, an

image or images generated from |

As set forth above, this term includes a

phrase that is indefinite within the recited

function; thus this term is indefinite.

Function: “selectively displaying on the

display device, in an unobtrusive manner

that does not distract a user of the |

16

of the apparatus

from a primary

interaction with

the apparatus, an

image or images

generated from

the set of content

data

(’652 claims 4, 5,

6, 7, 8, 11) |

the set of content data

STRUCTURE: One or more

digital computers programmed

to identify the next set of content

data in the schedule and display

the next set of content data in the

schedule in an “unobtrusive

manner that does not distract a

user of the apparatus from a

primary interaction with the

apparatus” |

apparatus from a primary interaction with

the apparatus, an image or images

generated from the set of content data” [as

construed herein]

To the extent there is any structure

disclosed that could fulfill the recited

function, it is:

Structure: A conventional digital

computer programmed with a screen saver

application program, activated by the

detection of an idle period, or a wallpaper

application program, that “selectively

displays … image or images generated

from the set of content data” [as construed

herein] |

The parties agree on the function associated with this means-plus-function limitation.

Additionally, the parties have separately proposed constructions for almost all of the terms

within this phrase. See § III.1 (“selectively displaying on the display device”); § III.3 (“in an

unobtrusive manner that does not distract a user of the apparatus from a primary interaction with

the apparatus”); § III.2 (“images generated from a set of content data”). The only additional

issue raised by this term is the identification of the structure associated with the function.

The specification teaches that the selective display of sets of content data is accomplished

in the following manner:

A set or sets of instructions for enabling a display device to selectively display an

image or images generated from a set of content data are also made available for

use by the content display systems. Typically, the instructions enable images

generated from content data to be displayed automatically, without user

intervention, in a predetermined manner, thereby enhancing the capability of the

invention to occupy the user’s peripheral attention.

’652 patent at 2:35-42. Fig. 5A of the patents and the accompanying description in the

specification set forth an algorithm that includes steps for accomplishing this function.

Specifically, in step 521, the system determines which set of content data is to be displayed next.

17

In step 105, the next set of content data is displayed. Interval’s proposed construction properly

identifies the structure that performs this function as a digital computer programmed to perform

these steps to display the content data in an unobtrusive manner that does not distract a user of

the apparatus from a primary interaction with the apparatus, where the “unobtrusive manner”

language is construed according to Interval’s construction set forth above in § III.3.

Defendants’ proposed structure is incorrect for three reasons. First, it confusingly and

unnecessarily limits the construction to “conventional” digital computers. A portion of the

specification that expressly discusses Fig. 5A, however, refers to all “digital computers” that

include a display device, without using the “conventional” language:

Like the method 100 (FIG. 1), the method 500 is performed by a content display

system 203 according to the invention which can be implemented, for example,

using a digital computer that includes a display device and that is programmed to

perform the functions of the method 500, as described below.

’652 patent at 24:61-66 (emphasis added). Nothing in the intrinsic record evidences an intent to

limit the claims to “conventional” digital computers and to exclude other types of digital

computers.

Second, Defendants’ proposed construction erroneously includes idle-time display

embodiments such as screensavers which, as discussed above in § III.3, does not display

information “in an unobtrusive manner” as required by this claim limitation.

Third, Defendants’ construction is incorrectly limited to display by a “wallpaper

application program.” Again, Defendants improperly attempt to limit the claims to a particular

embodiment. See Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1323 (“[A]lthough the specification often describes very

specific embodiments of the invention, we have repeatedly warned against confining the claims

to those embodiments.”). As discussed above, this limitation is satisfied when the display is

“during a user’s primary interaction with the apparatus and unobtrusively such that the images

18

generated from the set of content data are displayed in addition to the display of images resulting

from the user’s primary interaction.” See § III.3.

Finally, for the reasons discussed above, neither this limitation nor the separately

construed term containing the “unobtrusive manner” language is indefinite because the

specification provides an objective definition of what that language means. See supra § III.3.

6. “each content provider provides its content data to [a/the] content display

system independently of each other content provider”

| Claim Language | Interval’s Proposed Construction | |

“each content provider

provides its content data

to [a/the] content display

system independently of

each other content

provider and . . . ”

(’314 All Claims) |

No construction needed; in the

alternative: each content

provider provides its content

data to the content display

system without being influenced

or controlled by any other

content provider |

Each content provider transmits its

content data to [a/the] content

display system without being

transmitted through, by or under the

influence or control of any other

content provider |

The parties’ difference in this construction is that Defendants want to add a requirement

that the data not be “transmitted through [or] by” another content provider. This proposed

additional limitation is not required by the claim language and is contrary to the prosecution

history.

First, all that is required is that each content provider provides the content data

“independently,” which has a plain and ordinary meaning of “free from the influence, control, or

determination of another or others.” Webster’s New World College Dictionary, 4th ed. (2010), at

725 (Ex. B). So long as this requirement is met, it is immaterial whether the data transmission

happens to be routed through another content provider.

Second, during the original prosecution the patentee expressly removed the requirement

of “direct” transmission from the content provider to the content display system as part of the

19

amendment in which the language of this disputed term was added. The claims were rejected

based on U.S. Patent No. 5,819,284 (“Farber”), which taught aggregating content from multiple

content providers at a single server prior to providing the content to the content display system.

’314 patent file history, 10/23/2003 Response to Office Action, at 9 (IL_DEFTS0006293). The

claims were narrowed in certain respects to distinguish this prior art patent, but that amendment

also broadened the claims in other respects. Specifically, before this amendment, the claims

included a limitation requiring that the content providers provide the content data “directly to the

display device.” Id. at 2-8 (IL_DEFTS0006286-92). As part of this amendment, the “directly to

the display device” language was removed from the claims, while the language disputed here

was added. Defendants’ proposed construction, which precludes the possibility of content data

being transmitted “through” or “by” another content provider, is wrong because it reintroduces a

requirement of “direct” transmission that was expressly removed during prosecution.

7. “user interface installation instructions for enabling provision of a user

interface that allows a person to request the set of content data from the

specified information source”

| Claim Language | Interval’s Proposed Construction | Defendants’ Proposed Construction |

“user interface

installation

instructions for

enabling provision of

a user interface that

allows a person to

request the set of

content data from the

specified information

source”

(’652 claims 15-18) |

“instructions” for enabling

provision of an interface that

enables a person to request the set

of content data from a specific

source of information |

“instructions” that enable content

providers to install a user interface

in the content provider’s

information environment so that

users can request a particular set of

content data representing the

image(s) to be displayed from the

specified content provider |

In contrast to Interval’s straightforward interpretation of the language used in the claims,

Defendants seek to load this construction up with jargon apparently aimed at limiting it to a

20

particular specification embodiment and placing a new spin on the meaning of “content data”—a

term that is separately construed (see supra § III.2). Defendants’ proposal is improper on both

counts.

Defendants’ additional requirement that the user interface must be “in the content

provider’s information environment” is imported straight from a preferred embodiment in direct

contravention of Federal Circuit precedent. See ’652 patent at 16:9-16; Phillips, 415 F.3d at

1323 (“[A]lthough the specification often describes very specific embodiments of the invention,

we have repeatedly warned against confining the claims to those embodiments.”). It is especially

inappropriate to import the preferred embodiment in this definition because the specification also

broadly teaches that “[a]ny appropriate user interface can be used for enabling a user to directly

request a particular set of content data.” ’652 patent at 18:60-61; see also id. at 2:63-3:3 (“The

content data acquisition instructions can include . . . user interface installation instructions for

enabling provision of a user interface that allows a person to request a set of content data from a