|

|

| The Next Step in Apple's Thermonuclear War Against Android: Galaxy Nexus in Apple v. Samsung II ~pj |

|

|

Sunday, September 02 2012 @ 05:27 PM EDT

|

I'm sure you have seen the headlines about Apple filing an amended complaint [PDF] in the *other* litigation it has going against Samsung in Northern California before the same two judges, the Honorable Lucy Koh and the magistrate, the Hon. Paul Grewal. This is the litigation designed to obliterate the Galaxy Nexus from the US market, and it targets a long list of Samsung Galaxy devices, including the latest added in the amended complaint, the Galaxy S III and Galaxy Note II.

While the case is now moving into the main tent of Apple's anti-Android circus, the Samsung devices are flying off the shelves in America. People want them. But Apple doesn't want us to want them, or if we already do want them, they don't want us to be able to find them to buy them. And if we can find them, because Samsung comes up with workarounds, it wants to be sure Samsung's devices are uglier than Apple's and can't do as much. Noble values, indeed. Apple's weapons in this war are patents and design patents and trade dress and whatever there is at hand that the law foolishly puts into the hands of plaintiffs determined to use the courts against its competitors. P.S. That's not what courts are supposed to be for. And companies could try innovation instead of litigation. Apple wants us all to buy only Apple products (or any nonAndroid alternative), or that's what I get from all this. So if we keep buying Android products, Apple's strategy is apparently to make it such a dangerous hassle to sell Android that the vendors will either give up and go back to whatever else they were doing before Android came along -- explaining why Microsoft's reaction to the bizarre Apple

verdict in Apple v. Samsung I was to crow that the verdict was "good for Windows phone" -- or have to implement so many workarounds, their products are hideous to look at and can't do the typical things customers expect. That seems to be how Samsung views all this litigation too, as Apple trying to limit consumer choice. Incidentally, the foreman in Apple v. Samsung I, as I now call it, is still talking about that verdict, and talking and talking, but he never makes it better.

This other case between Apple and Samsung isn't about rectangles with rounded corners or double rows of icons with graphics of phone receivers or flowers. Same court, same judges, same parties, but different Apple patents. These Four Horsemen of the Android Apocalypse are patents for what Apple claims are “key” product features -- “Slide to Unlock,” “Text Correction,” “Unified Search,” and “Special Text Detection.” In other words, four toxic software patents. Yes, Apple claims to own that functionality as its very own, because it's such a great innovator. Who else could think up text correction? I mean, come on. They are Geniuses. I jest.

I've taken the time to read up on the case a bit, and I'd like to show you the dirty tricks Google, a nonparty involved in the case due to Apple's discovery demands, said back in April Apple was doing -- creating what Google called a "manufactured controversy". It'll give you some insight into this thermonuclear war Apple is waging.

Why Design Patents Are So Dangerous

So this isn't a design patent case. By the way, if you want to understand just how toxic design patents are, let me show you something.

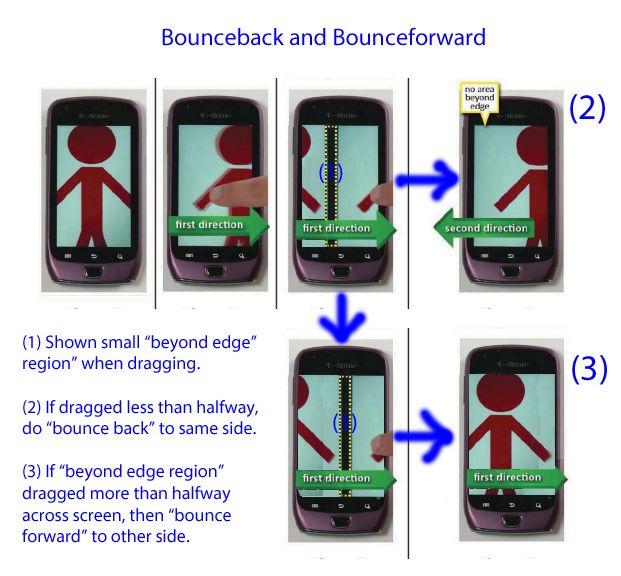

Bruno Bowden sent me this on August 27, a simple workaround to the Apple bounceback patent. The verdict was on the 24th, and he didn't immediately start to work on this. In short, it was quick. He calls it "Bouncebackandforth":

Here's why he thinks it's better than Apple's patent:

May I present "Bouncebackandforth". Really quite simple. It has elements of

the Diamond Touch prior art. To my mind this would've been distinctive

enough for the jury to find it to be non-infringing. It is also arguably

better than the Apple design as it allows you to quickly switch from one

edge of a document to the other. So as you scroll off the end of the doc,

you can switch back to the start....At least it makes a fair attempt to be

different and I like that it offers some utility as well.

There could be other patents that this workaround bumps into, because heaven only knows you can't code an inch without bumping into somebody's patent these days, so don't use it without asking your lawyer, but my point is that it wasn't hard to come up with a good possibility fairly rapidly. But, in contrast,

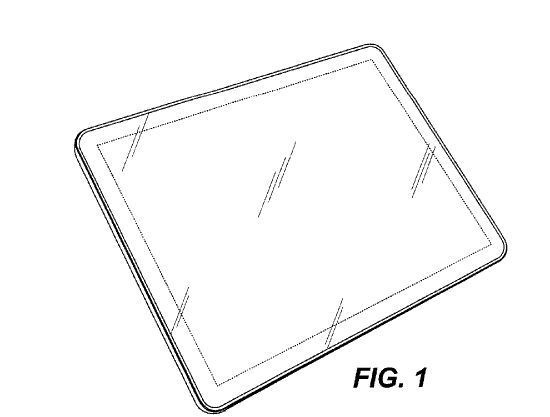

here's the Apple design patent, D504889, about those rounded corners -- how do you code around it? A tablet in the shape of a parallelogram?:

How different can it look and still be a tablet? It can't be a diamond shape, or it'll put out somebody's eye. An egg shape? That's impractical too. And that's what makes Apple's new foray into design patents so damaging. Your options are incredibly limited, because Apple took the most common shape for tablets since at least the Sumerians, planted its iFlag and claimed it as its own. Why did the USPTO allow this to happen?

Apple in Discovery

We'll eventually get a Timeline for Apple v. Samsung II done, so you can see the full flow of the case, which is currently set for a March 31, 2014 trial date, but for now, I want to show you what Google told the court about Apple's behavior. It's this document [PDF], titled NON-PARTY GOOGLE INC.’S OPPOSITION TO APPLE INC.’S MOTION TO COMPEL DISCOVERY OF DOCUMENTS, INFORMATION OR OBJECTS, and I've done it as text for you, because I know you don't read PDFs much and scribd is hard to deal with. I also want to be sure the document is searchable. From Google's filing, you'll get the flavor of what was going on: The primary issue for the Court to resolve, however, remains the timing of Google’s document production. Google has committed to produce testimony regarding the accused functionality, and has already offered one deposition that Apple has refused to take. Google has

also committed to produce source code compiled into the accused device, and could have completed this production in time for Apple’s brief had Apple served its subpoenas when it should have, on February 22, 2012. But by April 5, when Apple decided to serve its subpoenas, Google could not, by the Court’s deadline for Apple’s reply brief, complete the complex and interdependent processes of locating, gathering and collecting documents; ensuring that its collection was complete; assembling and training a document review team; supervising and completing responsiveness review; resolving any second-level questions generated during this review; reviewing for privilege; and formatting and verifying the documents for production. Apple tenders a single, sad excuse for its delay: it claims that it could not subpoena Google before asking the Samsung defendants and counterclaimants (“collectively, “Samsung”) to produce the source code running on the Galaxy Nexus. But Apple cannot square this excuse with the now-too-long history of Apple’s Android-related litigation, which shows Apple’s firm understanding that only Google could provide the source code underlying the Galaxy Nexus.

As everyone in the mobile industry knows, Android devices largely fall into two categories: a small number of “lead devices” bearing Google’s “Nexus” trademark and running Google’s stock build of Android, and other devices including software customized by the device maker, or OEM. For a major Android release – such as Ice Cream Sandwich – Google and an OEM together launch a lead device running the new release. Critically, Google retains control of lead devices’ platform software, providing the OEM with only binaries for installation. For lead devices, Google is the authoritative source – indeed, the only source – from which to obtain original, pre-compilation Android platform code. This has been widely reported, discussed, analyzed and debated in the technology press and the mobile industry. Indeed, Google itself promoted the Samsung Galaxy Nexus as a lead device including “the best Google mobile services and fastest updates directly from Google.” (Martin Decl. Ex. 1.) Apple’s own litigation filings show that it knew all this at least as early as August 2010, and probably earlier than that. Indeed, since then, Apple has subpoenaed Google nine times in at least eight different actions regarding Android, each time demanding source code for lead devices, and Google has repeatedly produced this source code in response....

Apple has known that OEMs control the build process for non-lead devices, but that Google controls the build process for lead devices, providing OEMs only with compiled binaries. (See supra § A.) Armed with this knowledge, Apple has sought and received lead-device source code from Google at least four times. (Id.) Despite this actual knowledge, in this action Apple engaged in a sham attempt to obtain from Samsung information it knew Samsung did not have, seeking delay in order to engineer an emergency.

Why is Apple sending a subpoena to Samsung for code it already knows only Google can supply? While I can't read Apple's mind, at least one possibility is that it was manufacturing a controversy so as to annoy the other side, to make Samsung (and any other Android vendors watching from the peanut gallery) decide that using Android isn't worth it, by piling on issues in discovery that require extra motion practice and time on a lawyer's money clock. Another possibility is that it was manufacturing a case to try to prove Samsung wasn't obeying discovery rules.Why is it asking for such broad discovery anyway, way beyond what is normal? Maybe so they'd say no and then they would have to do more motion practice over the manufactured controversy? Maybe because it has even bigger plans on what to do with any scraps of usable information it might like to use later against Google in other ways? You think?

By the way, Google mostly prevailed [PDF] in this matter, but while Apple had to back off on its very, very broad fishing expedition demands, it still got away with plenty, if one assumes that Google's representations are accurate. (Note the letter, quoted in the filing, from Google to Apple offering Apple an early deposition opportunity, one which Apple declined.)

For those who would like to read them, here are all the Apple patents in play in this case:

- 5,946,647 (the “’647 Patent”), System and method for performing an action on a structure in computer-generated data

- 6,847,959 (the “’959 Patent”), Universal interface for retrieval of information in a computer system

- 8,046,721 (the “’721 Patent”), Unlocking a device by performing gestures on an unlock image

- 8,074,172 (the “’172 Patent”), Method, system, and graphical user interface for providing word recommendations

- 8,014,760 [Part 2] (the “’760 Patent”), Missed telephone call management for a portable multifunction device

- 5,666,502 (the “’502 Patent”), Graphical user interface using historical lists with field classes

- 7,761,414 (the “’414 Patent”), Asynchronous data synchronization amongst devices

- 8,086,604 (the “’604 Patent”), Universal interface for retrieval of information in a computer system

The case has all those, but the preliminary injunction they've been arguing about forever is only about the four that Apple believed were so clear no claim construction would be required. You can see that in this transcript [PDF] of the May 2nd hearing on all this.

Here we go, the filing as text, followed by the magistrate's order:

Amy H. Candido

[email]

Matthew S. Warren

[email]

QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART

& SULLIVAN, LLP

[address, phone, fax]

Attorneys for Non-Party Google Inc.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN JOSE DIVISION

APPLE INC., a California corporation,

Plaintiff,

v.

SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO., LTD., a

Korean corporation; SAMSUNG

ELECTRONICS AMERICA, INC., a New

York corporation, and SAMSUNG

TELECOMMUNICATIONS AMERICA,

LLC, a Delaware limited liability company,

Defendants.

_______________

CASE NO. 12-CV-00630-LHK

NON-PARTY GOOGLE INC.’S

OPPOSITION TO APPLE INC.’S

MOTION TO COMPEL DISCOVERY OF

DOCUMENTS, INFORMATION OR

OBJECTS

Hearing:

Date:

May 1, 2012

Time: 10:00 a.m. PDT

Place: Courtroom 5, Fourth Floor

Judge: Hon. Paul S. Grewal

This is a manufactured controversy. Plaintiff and counterclaim-defendant Apple Inc. (“Apple”) delayed in serving non-party Google Inc. (“Google”) with two expansive subpoenas, running out the clock for six full weeks after the Court authorized discovery relevant to its motion for a preliminary injunction. Apple sought from Google, on an extremely accelerated time-frame, documents and testimony regarding a broad swath of information including, for example, all communications between Google and Samsung relating to any aspect of Android; all communications between Google and Samsung relating to any aspect of Apple or its products, and all documents regarding those communications; and any analysis of Apple products, whether or not related to the accused functionality or even to Android. Google had three responses. First, Google objected to requests seeking information beyond the accused functionality, such as all communications with Samsung regarding any aspect of Android, as burdensome, irrelevant and unauthorized by the Court’s order allowing “discovery relevant to the preliminary injunction motion.” Second, Google explained that Apple’s delay in serving its subpoena prevented it from producing most documents in time for Apple to file its reply brief, although Google could and would produce source code compiled into the accused device – which Apple agreed was its highest priority – and could also produce witnesses to testify regarding the accused functionality. Third, Google requested that Apple slightly modify the protective order governing confidentiality of Google’s highly confidential source code, as Apple and Google have done in other actions.

Apple initially appeared amenable to negotiation, but then turned on a dime, declared it was filing a motion to compel, and refused to narrow a single request in either subpoena. Google repeatedly pressed Apple to narrow the issues in dispute, and Apple repeatedly refused. Tellingly, Apple failed to allow the in-person lead counsel meet-and-confer discussion the Court has required before discovery motions in this action. As a result, Apple’s motion includes far too many issues, including some on which the parties should have reached agreement, and some which are premature.

The primary issue for the Court to resolve, however, remains the timing of Google’s document production. Google has committed to produce testimony regarding the accused functionality, and has already offered one deposition that Apple has refused to take. Google has

1

also committed to produce source code compiled into the accused device, and could have completed this production in time for Apple’s brief had Apple served its subpoenas when it should have, on February 22, 2012. But by April 5, when Apple decided to serve its subpoenas, Google could not, by the Court’s deadline for Apple’s reply brief, complete the complex and interdependent processes of locating, gathering and collecting documents; ensuring that its collection was complete; assembling and training a document review team; supervising and completing responsiveness review; resolving any second-level questions generated during this review; reviewing for privilege; and formatting and verifying the documents for production. Apple tenders a single, sad excuse for its delay: it claims that it could not subpoena Google before asking the Samsung defendants and counterclaimants (“collectively, “Samsung”) to produce the source code running on the Galaxy Nexus. But Apple cannot square this excuse with the now-too- long history of Apple’s Android-related litigation, which shows Apple’s firm understanding that only Google could provide the source code underlying the Galaxy Nexus.

As everyone in the mobile industry knows, Android devices largely fall into two categories: a small number of “lead devices” bearing Google’s “Nexus” trademark and running Google’s stock build of Android, and other devices including software customized by the device maker, or OEM. For a major Android release – such as Ice Cream Sandwich – Google and an OEM together launch a lead device running the new release. Critically, Google retains control of lead devices’ platform software, providing the OEM with only binaries for installation. For lead devices, Google is the authoritative source – indeed, the only source – from which to obtain original, pre-compilation Android platform code. This has been widely reported, discussed, analyzed and debated in the technology press and the mobile industry. Indeed, Google itself promoted the Samsung Galaxy Nexus as a lead device including “the best Google mobile services and fastest updates directly from Google.” (Martin Decl. Ex. 1.) Apple’s own litigation filings show that it knew all this at least as early as August 2010, and probably earlier than that. Indeed, since then, Apple has subpoenaed Google nine times in at least eight different actions regarding Android, each time demanding source code for lead devices, and Google has repeatedly produced this source code in response.

2

For all these reasons, Apple could and should have subpoenaed Google – not to mention carriers such as Verizon that sell the lion’s share of Galaxy Nexus devices – on February 22, 2012, the day the Court allowed preliminary-injunction discovery. Apple’s eventual subpoenas contained nothing unique to this action; to the contrary, every request is word-for-word or substantially identical to requests from prior Apple subpoenas – usually many times over. Instead Apple ran out the clock for six weeks, leaving Google insufficient time to respond to the subpoenas. The Court should therefore deny Apple’s motion to compel in its entirety, allowing Google to produce documents regarding the accused functionality during normal Rule 26 discovery, instead of rewarding Apple’s overbroad requests and unjustified delay.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

A. Apple Commences a Broad Campaign of Litigation Against Various Android

Device Makers, and Repeatedly Subpoenas Google in Each Action, Seeking

the Same Information Apple Now Contends It Didn’t Know Google Had

On March 2, 2010, Apple filed three actions against HTC, alleging infringement of twenty patents. Certain Personal Data and Mobile Communications Devices and Related Software, Inv. No. 337-TA-710 (U.S.I.T.C.); Apple Inc. v. High Tech Computer Corp. et al., No. 10-166 (D. Del.); Apple Inc. v. High Tech Computer Corp. et al., No. 10-167 (D. Del.). Although Apple’s District Court actions and its I.T.C. investigation named only HTC, much of Apple’s ire was directed at Google. As quoted by his biographer, Apple’s founder and CEO Steve Jobs stated:

Our lawsuit is saying, “Google, you . . . ripped off the iPhone, wholesale ripped us off.” Grand theft. I will spend my last dying breath if I need to, and I will spend every penny of Apple’s $40 billion in the bank, to right this wrong. I’m going to destroy Android, because it’s a stolen product. I’m willing to go thermonuclear war on this.

(Martin Decl. Ex. 2 at 3.) Apple was true to its founder’s word. Since filing the first action and investigation against HTC, Apple has brought no fewer than eight actions against HTC, Motorola and Samsung. Certain Mobile Devices and Related Software, Inv. No. 337-TA-750 (U.S.I.T.C.); Certain Electronic Digital Media Devices and Components Thereof, Inv. No. 337-TA-796 (U.S.I.T.C. ); Certain Portable Electronic Devices and Related Software, Inv. No. 337-TA-797 (U.S.I.T.C. ); Apple Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., No. 11-8540 (N.D. Ill.); Apple Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., No. 10-23580 (S.D. Fla.); Apple Inc. v. Motorola Mobility, Inc., No. 12-20271 (S.D. Fla.); Apple

3

Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., No. 11-1846 (N.D. Cal.); this action. Apple has subpoenaed Google in each of these actions, and in various actions has repeatedly sought from Google production of source code for its lead devices.

This is no surprise: Apple’s first Android litigation, Apple v. HTC, Inv. No. 337-710 before the International Trade Commission, established that Apple understood full well Google’s role in Android development, as well as the difference between lead devices (controlled by Google) and other devices (controlled by OEMs). In that investigation, Google moved to quash portions of Apple’s overbroad subpoena, including requests seeking Google’s knowledge of source code on devices controlled by HTC. As the ALJ explained in issuing his order, Google’s argument depended on the distinction between lead and non-lead devices:

Google additionally submits that the deposition topics are overbroad and unduly burdensome “because Google does not have, and cannot be expected to have, detailed knowledge of how HTC’s products work, as opposed to how the Android platform works before it is modified by HTC.” Id. In that regard, Google states that it develops Android source code and makes it freely available under an open source license for downloading and customization for use in a product. “After receiving the Android code, HTC and others are free to add, delete or modify any portion of such code to suit their needs.” Id.

Nonetheless, Google acknowledges that three exceptions apply with respect to HTC. Google states that it does have information regarding the Android software to be used in the HTC Nexus One Handset, the HTC Dream (marketed as the T-Mobile G1) handset, and myTouch 3G handset. Google is, therefore, willing to provide a witness to testify regarding its knowledge of the Android code installed in these three products.

(Martin Decl. Ex. 3 at 3-4.) Thus as far back as September 28, 2010, Google explained to Apple, and Apple understood, that OEMs could provide information regarding source code compiled into non-lead devices, while Google could provide information regarding lead devices – including the first “Nexus” branded lead device, the Nexus One. Indeed, on October 28, 2010, Google produced a computer containing source code compiled into the lead devices. (Martin Decl. Ex. 4.)

Apple kept suing Android device makers, and Apple and Google fell into a familiar pattern: Apple would subpoena Google seeking information including source code for lead devices, and Google would provide that information. Over and over again, Apple demonstrated its understanding that Google could provide lead-device code, while OEMs could provide code for other devices. For example, in Certain Mobile Devices and Related Software, No. 337-TA-750 (U.S.I.T.C.), Apple “confirmed that in this investigation Apple seeks [from Google] only Android

4

operating system files for builds corresponding to the two accused Motorola lead devices: the Motorola Droid and Xoom.” (Martin Decl. Ex. 5.) Google produced a computer containing this source code. (Martin Decl. Ex. 6.) Similarly, in Apple Inc. v. Motorola Inc. et al., No. 11-01846 (N.D. Ill.), Apple acknowledged that Google need produce only source code for the same two devices (Martin Decl. Ex. 7 at 3), and Google again produced a source-code computer. (Martin Decl. Ex. 8.) Finally, in Apple Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., et al., No. 10-23580 (S.D. Fla.), Apple again confirmed that it sought source code and testimony regarding the same two accused lead devices. (Martin Decl. Ex. 9.) Again, Google produced a computer containing this highly confidential source code. (Martin Decl. Ex. 10.)

B. Google and Samsung Promote the Galaxy Nexus as a Google Lead Device

On December 15, 2011, the Galaxy Nexus went on sale in the United States. (Docket No. 10 at 7.) Google directly promoted the Galaxy Nexus, including video advertisements under the “Google Nexus” brand at http://www.youtube.com/user/googlenexus/custom, as well as a web site at http://www.google.com/nexus/. Under the first tab, “features,” this Web site stated:

(Martin Decl. Ex. 1.) If this were not enough, Google’s contribution to the Galaxy Nexus was firmly shown by software on the phone itself: when turned on or rebooted, the first word displayed by the Galaxy Nexus is “Google.”

The Galaxy Nexus received extensive media coverage in both technology blogs and mainstream media, which emphasized its role as Google’s lead device for the Ice Cream Sandwich Android release. See, e.g., Martin Decl. Ex. 11 (calling the Galaxy Nexus “the newest Google phone”); Martin Decl. Ex. 12 (describing “Google’s line of Nexus smartphones” and the Galaxy Nexus as “the launch device for Google’s highly anticipated new version of Android – Ice Cream Sandwich – the company’s most significant mobile OS update yet”). In short, even if Apple did not know that the Galaxy Nexus was a Google-branded, lead device with code maintained by

5

Google – and the conduct of prior litigation between Apple and Google firmly establishes that Apple did know all this – there was no way it could have avoided learning this information from the coverage of the product launch.

C. Despite Knowing It Should Promptly Subpoena Google, Apple Delays Doing

So For Six Weeks, Instead Engaging in the Empty Exercise of Asking

Samsung Questions to Which Apple Already Knew the Answers

On February 8, 2012, Apple filed this action as well as its motion for a preliminary injunction. (Docket Nos. 1, 10.) On February 22, the Court entered its Order Setting Briefing and Hearing Schedule for Preliminary Injunction Motion, which authorized “discovery relevant to the preliminary injunction motion.” (Docket No. 37 at 2:4.) Although one would normally expect Apple – which stated in its motion for a preliminary injunction that resolution of this matter was “essential to prevent immediate and irreparable harm to Apple” – to subpoena Google the next day, Apple did not do so. (Docket No. 10 at 1.) Indeed, Apple did not even serve discovery on Samsung until two weeks later, on March 6, 2012. Despite knowing that it should seek source code from non-party Google (see supra §§ A, B), Apple sought this code only from Samsung. Of course, Samsung responded that that the “source code for the version of Ice Cream Sandwich used on Galaxy Nexus was written by Google, not Samsung, Samsung does not have possession of the source code; Google provides Samsung with object code in binary form to be installed onto the Galaxy Nexus.” (Martin Decl. Ex. 13 at 7.) Still Apple did not subpoena Google. Instead Apple waited two more days, and then told Samsung that its responses were somehow insufficient – although it is difficult to imagine what could be unclear about Samsung’s description regarding the source code. (Martin Decl. Ex. 14 at 1.) Samsung again replied, stating: “As Samsung made clear in these interrogatory responses – and as Samsung states once again – the source code for the version of Ice Cream Sandwich used on Galaxy Nexus was written by Google, not Samsung. Samsung does not have possession of that source code. To Samsung’s knowledge, the only company in possession of the source code used on Galaxy Nexus is Google.” (Martin Decl. Ex. 24.) No longer able to bury its head in the sand, Apple finally subpoenaed Google on April 5, 2012. But by then over six weeks had elapsed since the Court allowed discovery, while Apple first did nothing and then engaged in the empty exercise of asking Samsung for source code it

6

knew was held by Google. Worse, there was nothing new in Apple’s subpoenas; to the contrary, all of their topics were word-for-word or substantially identical to requests from prior Apple subpoenas – usually many times over. (See generally Appendix A.) In short, there was no reason whatsoever for Apple to wait a single day to subpoena Google after the Court allowed preliminary injunction discovery on February 22, 2012. Instead, of course, Apple waited six weeks.

Those lost weeks were critical: instead of having eleven weeks to respond to Apple’s subpoena before Apple filed its brief, Apple’s delay tactics gave Google just five. The collection required by Apple’s broad subpoena is a challenging one. Apple seeks (at the very least) detailed technical information regarding four disparate areas of Android software. Two of the teams developing accused functionality – the Quick Search Box and the Android Keyboard – are located in London and Tokyo. Simply to complete its technical production, Google must collect documents from all four teams, including some in Japanese; confirm that the documents it has collected are complete; assemble and train a document review team; supervise and complete review for responsiveness to the Subpoenas; consider and resolve the second-level questions that inevitably arise during first-level review; review responsive documents for privilege and resolve second-level questions that arise during this review; and supervise the vendor’s formatting and verification of documents for production. These steps take 4-6 weeks to complete even for the simplest document production. This production Apple seeks in this action is more complex and, as a result, for Apple’s requested production the minimum time to produce technical documents is 6-8 weeks. But of course, because of Apple’s needless six-week delay, by the time it received the Subpoenas Google had only five weeks to complete its technical production.

D. Apple Refuses to Take the Deposition of Ken Wakasa, Whom Google Offered

For Deposition on Friday, April 27, 2012, the Same Date on Which Apple

Requested a Much Broader Deposition on All Its Noticed Topics.

Apple requested testimony from Google on 12 topics, including all four of the accused technologies. (Docket No. 135-1, Ex. 3.) Apple stated firmly: “The deposition will begin at 9:30 on April 27, 2012.” One of Google’s declarants and designees, Ken Wakasa, lives and works in Japan but was visiting Mountain View for unrelated reasons. Google seized this opportunity and offered him for deposition a day earlier than Apple wanted, on April 26, 2012. Usually attorneys

7

prosecuting preliminary injunction motions “essential to prevent immediate and irreparable harm” to their clients are thrilled to receive offers of early depositions. (Docket No. 10 at 1.) Not Apple in this case, though. Instead Apple called Google on April 23, 2012, to say a Thursday deposition fell too soon after Samsung’s Monday brief. (Martin Decl. Ex. 15.) Later that day, Google wrote Apple to re-offer Mr. Wakasa on April 27, 2012, the date on which Apple originally requested a much broader deposition:

I write to finalize plans regarding the deposition of Ken Wakasa. As we discussed today, Mr. Wakasa lives and works in Tokyo, Japan, as does the team responsible for Android Keyboard, which Apple has accused of infringing the '172 patent. For unrelated reasons, however, Mr. Wakasa is in Mountain View for the rest of this week. Next week is Golden Week in Japan when, as I'm sure you know, the country essentially shuts down. For the two weeks after that, business and family commitments prevent Mr. Wakasa from leaving Japan; again, as you know, it would be illegal to depose him there.

For all these reasons, we offered Mr. Wakasa on Thursday, April 26. In response, you said Apple could not be ready in time for this deposition, because it fell too soon after Samsung's opposition brief. In light of your statements, Mr. Wakasa has rearranged his schedule so he can be deposed a day later, Friday, April 27, 2012. The deposition will commence at 8:00 a.m. PDT, and will have a hard stop at 4:00 p.m. PDT, so that Mr. Wakasa can make his flight back to Japan in time for Golden Week.

We expect Apple to depose Mr. Wakasa on Friday. As you know, Apple’s notice of deposition sought testimony that day on all four preliminary injunction patents. If you cannot actually take a deposition on only one of those patents, then we question the urgency of your case.

(Id. at 1-2.) Amazingly, Apple again refused to proceed with Mr. Wakasa’s deposition, even on the date it itself had noticed. (Martin Decl. Ex. 16 at 2.) Google repeated that Mr. Wakasa’s schedule gave no leeway to proceed at an alternative time, and that Mr. Wakasa’s deposition would go forward as originally noticed by Apple. (Martin Decl. Ex. 17.) Apple did not reply. Google’s counsel, Samsung’s counsel, and Mr. Wakasa arrived for his deposition at 8:00 a.m. PDT this past Friday, but Apple did not attend.

E. Apple Has Not Confirmed Or Even Addressed Google’s Other Depositions.

Aside from Mr. Wakasa, Google has offered deposition dates for its other four declarants, and has designated them as Google’s witnesses under Rule 30(b)(6) on deposition topics 2, 7 & 8. (Martin Decl. Ex. 18 & 19.) All of Google’s witnesses rearranged their very busy schedules, and Mr. Clark and Mr. Bringert agreed to travel thousands of miles to the Northern District of

8

California, in order to make these depositions possible in the limited time available. Apple has not confirmed these depositions or even responded to Google on this point.

F. Apple Flouts This Court’s Order Requiring a Pre-Motion, In-Person Meet-

And-Confer Discussion Among Lead Counsel, Admitting It Is Doing So But

Contending the Requirement Does Not Apply Because Google Is Not a Party

Instead of working with Google to schedule depositions and address other issues between Apple and Google, Apple told Google its positions were non-negotiable and proceeded to file its motion to compel. In so doing, Apple ignored the Court’s repeated and firm orders, in both this action and the prior action between Apple and Samsung, allowing discovery motions only after lead counsel meet and confer – and do so in person. When Google challenged Apple on this point, Apple stated that this rule does not apply because Google is not a party to this action. Apple’s Motion thus flouts both the letter and the spirit of the Court’s repeated rulings.

On August 24, 2011, the Court first barred discovery motions without a pre-motion, in- person meet-and-confer discussion among lead counsel:

THE COURT: I’m going to require, and I’m sure he will agree, that lead trial counsel have to meet in person to meet and confer on any discovery dispute before your file a motion. Okay?

MR. MCELHINNY: Thank you, Your Honor.

(Martin Decl. Ex. 20 at 83:11-15.) The Court evidently considered this requirement to be successful because, in allowing discovery to commence, the Court also ordered:

The Court encourages the parties to make all efforts to keep discovery requests reasonable in scope and narrowly tailored to address the preliminary injunction motion. If disputes arise, the parties must make a good faith effort to reach a mutually agreeable compromise, and lead trial counsel must meet and confer in person, before bringing the dispute before the Court.

(Docket No. 37 at 2:7-10.) Apple has attempted to avoid this requirement before. At a hearing on September 28, 2011, Apple asked this Court for “anything in other cases that you have found satisfactory as a substitute for lead counsel meeting and conferring in person that you would be open to . . . .” (Martin Decl. Ex. 21 at 4:23 – 5:2.) This Court firmly declined to alter the requirement. (Id. at 5:5-9.) When Apple and Samsung again asked the Court for relief from the in-person, lead-counsel meet-and-confer requirement, the Court again firmly declined to alter the

9

requirement. (No. 11-1846, Docket No. 811.) The Court’s intention could not be clearer: no discovery motions can proceed without an in-person meeting between lead counsel.

Despite all this, Apple refused to obey the Court’s order and file its motion only after completing the required in-person meet-and-confer discussion. When Google requested an in- person meet-and-confer discussion (Martin Decl. Ex. 22.), Apple responded that the in-person meet-and-confer requirement “applies only to disputes between the parties in the case.” (Martin Decl. Ex. 23.) Google repeatedly asked Apple to explain the basis for this view (e.g., Martin Decl. Ex. 20.) but Apple refused.

ARGUMENT

Largely because of Apple’s failure to meet and confer, the Court must address far too many issues in resolving this motion. First, the Court must determine whether it can be heard at all, given Apple’s failure to allow the required in-person meet and confer between lead counsel. Should it allow the motion to proceed, the Court would next consider the scope of Google’s production, and whether it must include documents far afield of the accused functionality, which Apple continues to demand. Third, the Court would consider the timing of Google’s production of documents, which Apple contends must be immediate, despite Google’s explanation that this simply cannot be so. Fourth and related, the Court must rule on Apple’s apparent request to re- depose Mr. Wasaka, despite its failure to take his deposition on the date originally noticed by Apple. Fifth, the Court should determine whether to grant non-party Google additional protections under the protective order governing confidentiality in this action. Sixth and finally, the Court should address Apple’s other arguments regarding possible future objections, which it can easily dismiss as premature.

I. The Court Should Deny Apple’s Motion Outright For Its Failure to Undertake the

Required In-Person, Pre-Motion Meet and Confer Between Lead Counsel, Thus

Flouting the Court’s Repeated Orders Requiring Such Conferences

There is no dispute that Apple’s “lead trial counsel” did not “meet and confer in person, before bringing the dispute before the Court.” (Docket No. 37 at 2:7-10.) Apple’s Motion admits that its meet-and-confer efforts are fully described in Jason Lo’s declaration (Motion at xvi:8-13), but Mr. Lo’s declaration describes only telephonic discussions between non-lead counsel.

10

(Docket No. 135-1 ¶ 6.) Tellingly, Apple’s motion does not address or even mention its utter failure to follow the Court’s repeated Orders, although Google had repeatedly stated its belief that Apple was in violation. Apple earlier told Google that “Judge Koh’s order” requiring pre-motion in-person meet-and-confer “applies only to disputes between the parties in the case.” (Martin Decl. Ex. 23.) Apple is evidently referring to the word “parties” in the second sentence below:

The Court encourages the parties to make all efforts to keep discovery requests reasonable in scope and narrowly tailored to address the preliminary injunction motion. If disputes arise, the parties must make a good faith effort to reach a mutually agreeable compromise, and lead trial counsel must meet and confer in person, before bringing the dispute before the Court.

(Docket No. 37 at 2:7-10.) There are two sensible ways to read this order, and one nonsensical one; Apple of course has chosen the latter. Google believes the order requires any party to a discovery dispute, whether or not also a party to the case, to meet and confer before filing a discovery motion. Thus, for example, the order would require Google to meet and confer in person before filing a motion to quash. It would also be reasonable, although Google believes incorrect, to read the Order as governing only Apple and Samsung, as parties to the action, in any discovery dispute. It is patently unreasonable, however, to read the Order as applying only to disputes Apple and Samsung have with each other, and not with non-parties such as Google. If the wording of the Order were not enough, the Court’s repeated Orders have made crystal clear its intention to restrain Apple and Samsung from filing discovery motions; Apple’s reading would flip the order to protect Apple and Samsung more than non-parties such as Google. This reason cannot be squared with the Court’s strong history of enforcing the Order.

Apple’s failure to honor the Court’s order also aptly illustrated the reasons for the Court’s order itself. Apple’s non-lead counsel refused during any meet and confer to narrow any of Apple’s requests, indicate which portions of those requests he felt were most important, or engage in any meaningful discussion with Google about anything. Instead Apple’s position, stated repeatedly, was that Google should produce 100% of the documents Apple demanded before Apple filed its brief – even though Google explained it was impossible to do so. The Court need not take our word for it; that is how Apple’s non-lead counsel himself summarized his position during the parties’ all-too-brief telephonic discussions:

11

Second, we wholeheartedly agree that Judge Koh encouraged “the parties to make all efforts to keep discovery requests reasonable in scope and narrowly tailored to address the preliminary injunction motion.” But we do not believe that this directive requires Apple to unreasonably narrow the scope of its discovery. As I have stated to both you and to Mr. Warren, Apple believes that the discovery it served on Google is appropriately narrow. Accordingly, while I am happy to discuss the issues further with you, we do not believe that the meet and confer rules require that we further narrow our already-tailored requests.

(Martin Decl. Ex. 25.) The Court ordered lead counsel to meet and confer in person precisely because such rigid and extreme positions rarely survive such meetings. Apple’s failure to tender its lead counsel, and the line adopted by its non-lead counsel, prevented any meaningful pre-motion meet and confer discussions from occurring. Google repeatedly asked Apple if there were particular documents it wanted; if there was a simpler subset of documents Google might be able to produce before Apple filed its brief on May 14, or if there was any other way the parties could narrow their differences. In response, Apple’s non-lead counsel simply repeated the statement above.

Apple’s failure to meet and confer as required is both undisputed and fatal, and the Court

should deny Apple’s motion for this reason alone. To rule otherwise would reward Apple for

flouting the Court’s authority, strongly encouraging its continued future violations of the Order.1

II. Apple Has Not Met Its Burden to Show That It Should Receive Discovery Beyond

That Agreed by Google

Apple’s motion addresses a mélange of topics, including many to which Google has already committed to provide documents or testimony, subject of course to its objections. Google has already agreed to produce testimony regarding Deposition Topics 2, 7 & 8, and has offered witnesses on these topics. (Martin Decl. Ex. 18 & 19.) Apple has not responded to this offer. Google has similarly agreed to produce testimony regarding Topic 5, although it cannot do so before Apple’s brief is due on May 14. Finally, Google has agreed, subject to its objections, to provide documents responsive to Request 6 & 8. Still, other topics remain in dispute. They have two things in common: each disputed topic seeks documents or testimony far afield of the

12

accused functionality; and, for each, Apple has not met its burden of showing entitlement to discovery.

A. Apple’s Request For “Differences” Between Open Source Code

and Code Compiled Onto the Galaxy Nexus is Irrelevant, Burdensome on Google, and

Would Reveal Google’s Trade Secrets Without Helping Apple in this Action

Google has agreed to produce source code compiled into the Samsung Galaxy Nexus, satisfying Apple’s need to understand what happens on the accused phone. But Apple goes further, demanding documents and testimony regarding “[t]he differences, if any,” between the code actually used on the accused phones and “the Android 4.0 Ice Cream Sandwich code publicly available from https://android.googlesource.com/platform/manifest, or through the process described at http://source.android.com/source/downloading.html.” This request has several flaws, each fatal.

1. The Open Source Code is Irrelevant to This Action Against Samsung

In this action, Apple accuses only Samsung of infringement; the preliminary injunction motion accuses only the Samsung Galaxy Nexus. Under these circumstances, the only software that affects Apple’s infringement analysis is software used by Samsung in the Galaxy Nexus; Google has already agreed to produce source code underlying that software. The open-source code is not loaded on Samsung’s Galaxy Nexus device and cannot be relevant to Apple’s infringement claims against Samsung generally or the Galaxy Nexus in particular.

2. Apple’s Request Would Reveal Critical Google Trade Secrets

Although Google releases some versions of Android through the Android Open Source Project, the internal functionality of Android running on the Samsung Galaxy Nexus is Google’s trade secret. Apple’s request would give attorneys for Apple – Google’s competitor and the architect of a sustained litigation campaign against Android device makers – access to every single difference between the open-source code and the proprietary code produced by Google. Apple could want this request for one purpose only – to design claims for other litigation. Of course, such a purpose is not permissible. Separately from the protective order governing this action, Apple has failed to meet its burden required to pierce Google’s trade secret:

13

[T]he requirements of relevance and necessity must be established where disclosure of a trade secret is sought . . . and that the burden rests upon the party seeking disclosure to establish that the trade secret sought is relevant and necessary to the prosecution or defense of the case before a court is justified in ordering disclosure.

Hartley Pen Company v. United States District Court for the Southern District of California, 287 F.2d 324, 325 (9th Cir. 1961); In re Apple & AT & TM Antitrust Litig., No. 07-5152, Docket No. 276, 2010 WL 1240295 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 26, 2010) (“Because the iPhone source code is a trade secret, plaintiffs have the burden to establish that it is both relevant and necessary.”) (citing Hartley Pen). Apple’s sole justification for this request is that it “seek[s] information regarding the computer code supplied by Google to Samsung for incorporation into the Galaxy Nexus.” (Docket No. 135 at 10:8-9.) But this request does not seek “information regarding the computer code supplied by Google to Samsung for incorporation into the Galaxy Nexus,” which Google has already agreed to provide, but rather information comparing that code to other code. Apple’s asserted justification is both tepid and false; it certainly cannot pierce the protection for Google’s trade secret.

3. Apple Does Not Need This Information to Litigate This Action

Apple has made this request in no fewer than five prior subpoenas to Google. (Appendix A at 2.) For the reasons stated above, Google has never provided this information. Nonetheless, Apple has managed to prosecute all of its pending Android actions, including through trial. There is a simple reason: Apple does not need this information to handle its current claims. Tellingly, Apple has provided no justification to the contrary.

B. Apple’s Requests Regarding Apple Products Are Greatly Overbroad, Seeking

Information Regarding Any Analysis of Any Apple Product – Information

Apple Has Been Barred From Obtaining in Other Android Litigation

In response to Requests and Topics Nos. 7 & 8, Google has already agreed to produce documents and testimony regarding “the design of, development of, implementation of and/or decision to implement” the accused functionality. To the extent “the design of, development of, implementation of and/or decision to implement” the accused functionality involved analysis of Apple products – a prospect which is quite doubtful, but which Google will carefully check – Google will produce documents and testimony regarding this analysis. But Apple wants more.

14

Requests and Topics Nos. 9 & 10 seek documents and testimony concerning analysis of “any Apple product, including but not limited to Apple’s products that incorporate any version of the iOS operating system as well as the Slide to Unlock, Text Correction, Unified Search, and Special Text Detection software, features, or functionality.” (Docket No. 135-1. Ex. 3 (emphasis added).)

Apple’s request for any analysis of “any Apple product” is greatly overbroad, and irrelevant to Apple’s claims in this action except when concerning the accused functionality – in which case any documents or testimony would already be responsive to Requests and Topics Nos. 7 & 8. Indeed, Apple’s sole justification for these requests is that “Google’s [alleged] efforts to copy the patented features is strong evidence that the patents are not obvious, i.e., invalid,” and that “Google’s [alleged] inability to design around the four patented features, moreover, relates to non-obviousness.” (Docket No. 135, 10:20 to 11:2 (emphasis added).) Apple cannot justify requests concerning any analysis of any Apple product from this thin gruel.

Finally, it would be greatly burdensome if not impossible for Google to comply with this request, which could require asking everyone at Google if they had ever analyzed an Apple product in the course of their employment. A search both so burdensome and so irrelevant cannot be permissible, and indeed Apple has already learned that it is not. In Apple v. HTC (I.T.C. 710), Google successfully quashed Apple’s narrower request seeking only communications regarding Apple products. (Martin Decl. Ex. 3 at 5.) The ALJ found deposition topics requiring “‘all communications’ regarding Apple or ‘any Apple product’” to be “unduly burdensome and impermissibly broad on their face.” (Id.) Apple’s requests here are much broader: they seek documents and testimony regarding Google’s alleged internal analysis rather than external communications. For the same reasons as in I.T.C. 710, the Court should bar Apple from pursuing the unreasonable Requests and Topics Nos. 9 & 10, relying instead on the narrower scope of Requests and Topics Nos. 7 & 8.

C. Although Apple’s Requests Regarding Consumer Surveys Are Overbroad,

And Apple Has Failed to Subpoena Companies With Relevant Knowledge,

Google Will Produce Any Documents Concerning the Accused Functionality

Topics and Requests 11 & 12 seek documents and testimony regarding “ importance to consumers and consumer purchasing decisions of” the accused functionality (Nos. 11) as well as

15

“the ability or capability to search the Internet on a phone or other mobile device.” (Nos. 12.) Apple should not be entitled to discover Google’s consumer surveys (if any) in a case that alleges infringement purely by Samsung. Until just this past week, Google did not even sell the Galaxy Nexus to consumers; the bulk of these sales in the United States have so far come from Verizon, which Apple has not subpoenaed. Nevertheless, to the extent they exist, Google will produce (subject of course to its objections) documents and testimony responsive to Topic and Request 11, which address the accused functionality. Topic and Request 12, however, go far beyond the accused functionality to documents concerning as well as “the ability or capability to search the Internet on a phone or other mobile device.” (Nos. 12.)

Apple admits this request does not address the accused functionality, structuring it as a separate request and noting that it seeks “Documents relating to the importance to consumers of the four accused, patented features as well as the importance to consumers of the ability to search the Internet using a mobile device.” (Docket No. 135 at 5:13-15.) Nowhere does Apple’s brief explain why or how the broad category of “the ability to search the Internet using a mobile device” relates to the accused functionality, nor can it. As a result, the Court should deny Apple’s motion regarding this request.

D. Apple’s Topic No. 1 is Nonsensical And, In Any Event, Waived

Apple’s Loc. R. 37-2 statement included Deposition Topic 1, which seeks testimony regarding “All documents and source code produced pursuant to Apple’s Subpoena to Produce Documents, Information or Objects served upon you on April 5, 2012, including without limitation the authenticity thereof.” But Apple’s brief does not address or even mention Topic No. 1, waiving any claim of relief. In any event, Google cannot possibly provide testimony regarding every single document it produces. The Court should deny any relief regarding Topic No. 1.

III. The Court Should Not Allow Apple to Benefit From Using Its Willful Blindness And

Delay to Engineer Its Own Emergency, And Then Asserting Its Manufactured

Emergency To Prejudice Google

Apple also requests that the Court order Google to produce documents very quickly, so that Apple can use them in preparing its reply brief. For two reasons, the Court should deny this request. First, Apple asks the impossible. As Google has explained to Apple, to complete its

16

technical production in this action Google must collect documents from all four teams, including some in Japanese; confirm that the documents it has collected are complete; assemble and train a document review team; supervise and complete review for responsiveness to the Subpoenas; consider and resolve the second-level questions that inevitably arise during first-level review; review responsive documents for privilege and resolve second-level questions that arise during this review; and supervise the vendor’s formatting and verification of documents for production. Google simply cannot complete these steps before Apple’s reply brief is due.

Second, Apple’s request regarding timing depends on the premise that it was surprised to discover that Google managed the build process for “Nexus” branded lead devices. But for at least the past eighteen months, Apple has known that OEMs control the build process for non-lead devices, but that Google controls the build process for lead devices, providing OEMs only with compiled binaries. (See supra § A.) Armed with this knowledge, Apple has sought and received lead-device source code from Google at least four times. (Id.) Despite this actual knowledge, in this action Apple engaged in a sham attempt to obtain from Samsung information it knew Samsung did not have, seeking delay in order to engineer an emergency. (Id.)

Apple’s motion thus rests entirely on a false premise: that Samsung was “stonewalling” by telling Apple the truth – a truth it already knew – and that Apple’s delay in subpoenaing Google was caused by anyone besides Apple. To make this argument, Apple conceals its own delay. Apple argues that Apple “immediately sought from Samsung information regarding Galaxy Nexus’ implementation of Ice Cream Sandwich.” (Docket No. 135 at 1:21-22.) This is not true, unless “immediately” means “thirteen days later” – for that is how long Apple waited to serve Samsung with its first discovery requests after the Court authorized preliminary injunction discovery. Similarly, Apple argues that it “promptly served Google with a subpoena” after Samsung explained it could not provide source code for the Galaxy Nexus because only Google held that code. (Docket No. 135 at 2:1.) Again, this statement is correct only if “promptly” means “nine days later” – the time between Samsung’s discovery responses and Apple’s service on Google of a retread subpoena it could have served on February 22, 2012. (See Appendix A.) Apple thus waited too long, not only by needlessly subpoenaing Samsung, but also by delaying its

17

requests to Samsung as well as its subpoenas to Google. The Court should not require Google to perform the impossible by producing documents on Apple’s schedule.

IV. The Court Should Not Order Witness Testimony Beyond What Google Has Offered

Again, Apple’s failure to meet and confer has required the Court to learn issues not in dispute between the parties. Google previously committed to provide witnesses on Topics 2, 7 & 8 regarding all of the accused functionality, and to do so before May 11, assuming Apple accepts the schedule Google proposed this past Tuesday, April 24, 2012. The Court must therefore resolve two issues: first, whether Apple is entitled to re-depose Mr. Wakasa; and second, whether Google must provide witnesses on any other topics.

A. The Court Should Not Reward Apple’s Refusal to Depose Mr. Wakasa

Google repeatedly told Apple that Mr. Wakasa could only be deposed this past Friday, April 27, 2012. (See supra § D). Notably, that same Friday was the date noticed by Apple for its 30(b)(6) deposition of Google on all twelve topics, not merely the ones for which Google designated Mr. Wakasa. (Id.) Despite picking the day, Apple simply refused to show up. Apple now seeks a new date for Mr. Wakasa, who has returned to his native Japan. It would be very burdensome on Mr. Wakasa, if it is possible at all, for him to leave Japan over the two weeks following the Golden Week. The Court should not reward Apple for refusing even to attempt to depose Mr. Wakasa, and should not compel his renewed deposition.

B. Google Cannot Provide Testimony on Topics 5 and 11 Before Apple’s Brief

Subject to its objections, Google has agreed to provide testimony on Topics 5 and 11. But it cannot do so before Apple must file its brief. Google is already preparing the four remaining witnesses it has committed to provide on Topics 2, 7 & 8 regarding the accused functionality. Because then nature of Topics 5 and 11 requires review of documents prior to testimony – unlike the accused functionality, which largely if not entirely requires only review of source code – Google cannot provide witnesses on these topics until it gathers, reviews and produces documents, which it cannot do before Apple’s brief for all the reasons already stated. The Court should therefore hold these depositions in abeyance until normal discovery.

18

V. The Court Should Enter Google’s Requested Prosecution Bar

As they have in prior cases, Google and Apple have agreed on a few modifications to the existing protective order governing confidentiality in this action. One area of dispute remains: Apple wishes to allow its litigation counsel, armed with knowledge of Google’s highly confidential source code, to participate in reexamination or reissue proceedings as long as they avoid “participating in or advising on, directly or indirectly, claim drafting or amending claims.” (Docket No. 135 at 18.) Google has asked Apple to articulate what attorneys could possibly do in reexamination or reissue proceedings that is not “participating in or advising on, directly or indirectly, claim drafting or amending claims,” but Apple declined to provide any examples. Apple’s brief provides one, and it is telling: Apple suggests that “District Court counsel . . . may have valuable accumulated knowledge on claim construction and prior issues.” (Id.) In Google’s view, claim construction certainly falls under “participating in or advising on, directly or indirectly, claim drafting or amending claims.” But this is precisely the problem – if Apple’s counsel are allowed to participate in reexamination or reissue proceedings, Google will never know how they are interpreting “participating in or advising on, directly or indirectly, claim drafting or amending claims,” and will therefore never know if it is adequately protected.

Apple has a great many attorneys; it can surely find sufficient staffing to cover any reexamination or reissue proceedings that may arise. Apple can cure its concerns by training more attorneys, or by declining to share Google’s highly confidential source code with all of its attorneys; but Google can never cure – indeed, will never know – if Apple’s lawyers interpret this malleable language in a manner that harms Google. The Court should therefore enter a prosecution bar with teeth, at least as applicable to highly confidential source code produced by non-party Google.

VI. Apple’s Remaining Arguments are Premature

Apple devotes considerable space in its motion to inventing disputes that do not yet exist. Apple devotes two pages to discussion of Google’s initial objections to its subpoenas, castigating them as “boilerplate.” But these issues are not yet ripe; Google is simply reserving objections it may make at a later time, when it actually produces documents. Similarly, Google has reserved

19

the right to assert a joint-defense privilege with Samsung. Apple does not contest that the privilege exists, but asks the Court to rule on privilege issues before Google has completed its production, or asserted any privilege. This is a classically unripe dispute, which courts are loathe to consider. Watts v. Allstate Indemnity Co., 2010 WL 4225561 at *3 (E.D. Cal. Oct 20, 2010). The Court in Watts succinctly summarized the problems with premature discovery motions:

The court, quite frankly, does not have the time to sort through an ill-conceived, unripe motion to compel, or worse yet, three of them. As set forth below, the court will order that the counsel in this case engage in civil, productive communication designed to elicit cooperation and the presentation of issues for the court to resolve in the future. What did become clear from the hearing was that the parties are still engaged in an ongoing meet and confer process and that there were very few issues properly before the court. What the undersigned also made clear is that although the court spent an inordinate amount of time seeking to provide the parties with guidance for going forward with discovery in this case, in the future the court will only rule on ripe, properly and narrowly presented issues which the parties have first attempted in good faith to resolve of their own accord. Very few of those issues are present in the instant dispute.

Id. The same is true here. Indeed, motions to compel privileged documents are categorically premature if filed before privileged documents have been identified and withheld, and parties have met and conferred concerning the privilege logs. See Nevada Power Co. v. Monsanto Co., 151 F.R.D. 118 at *122 (D. Nev. 1993). In Nevada Power, the court denied a motion to compel as “not ripe for consideration” because “Plaintiff filed the instant motion without first demanding production of the logs. Hence, meaningful attempts to resolve the dispute informally as required by Rule 190-1(f)(2) were foreclosed.” Id. The Court should deny the remainder of Apple’s motion as premature.

20

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons, the Court should deny Apple’s Motion in its entirety.

DATED: April 28, 2012

QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART &

SULLIVAN, LLP

/s Matthew S. Warren

Amy H. Candido

[email]

Matthew S. Warren

[email]

QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART &

SULLIVAN, LLP

[address, phone, fax]

Attorneys for Non-Party Google Inc.

_________

1 Of course, Apple’s failure to brief this issue at all, despite Google’s repeated statements that Apple was not in compliance, waives Apple’s right to bring any further arguments on this point.

21

If you'd like to read what Google was responding to, so as to hear Apple tell its own story, here is Apple's motion to compel, with all the exhibits:

And here's the Order:

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN JOSE DIVISION

APPLE INC., a California Corporation

Plaintiff,

v.

SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO., LTD, a

Korean corporation; SAMSUNG

ELECTRONICS AMERICA, INC., a New York

corporation; and SAMSUNG

TELECOMMUNICATIONS AMERICA, LLC,

a Delaware limited liability company,

Defendants.

________________

Case No.: 12-CV-00630-LHK (PSG)

ORDER GRANTING-IN-PART

APPLE’S MOTIONS TO COMPEL

(Re: Docket Nos. 96, 99, 135)

______________

In this patent infringement suit, Plaintiff Apple Inc. (“Apple”) moves to compel Defendants Samsung Electronics Co., LTD., Samsung Electronics America, Inc., and Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC (collectively “Samsung”) to respond to interrogatories and produce documents relevant to Apple’s discovery requests. Apple also moves to compel third-party Google to produce documents relevant to Apple’s request for production, and for Google to make a 30(b)(6) witness available to Apple for deposition. On May 1, 2012, the court heard oral argument

1

on Apple’s discovery motions. Having considered the arguments and evidence presented, the court hereby GRANTS-IN-PART Apple’s motions.

I. BACKGROUND

A. Apple’s Motion to Compel Responses to Interrogatory Nos. 4 and 8-10

On February 8, 2012, Apple filed a complaint for patent infringement and a motion for a preliminary injunction seeking to enjoin Samsung from making, using, offering to sell, selling within the United States, or importing into the United States, Samsung’s Galaxy Nexus smartphone.1 The parties are in the midst of active preparations for the June 7, 2012 hearing on Apple’s pending Motion for a Preliminary Injunction. On March 6, 2012, Apple served Samsung ten interrogatories pertaining to its Preliminary Injunction Motion.2

Samsung responded to Apple’s interrogatories on March 27, 2012, but did not respond to Interrogatory Nos. 4 and 8-10.3

Interrogatory No. 4 asks about Samsung’s knowledge of the four Apple utility patents at issue in the Preliminary Injunction (the “Preliminary Injunction Patents”), and any Samsung efforts to avoid infringement. Interrogatory No. 8 asks about any comparison Samsung made between any Apple product and any Samsung smartphone or tablet computer. Interrogatory No. 9 asks about Samsung’s discussions regarding the relationship between the features accused of infringing the Preliminary Injunction Patents and consumer preference for these features. Interrogatory No. 10 asks about Samsung’s discussions regarding the Preliminary Injunction Patents and their implementation into any Samsung product. Samsung objects to Interrogatory No. 4 on the grounds that Samsung’s knowledge of the Preliminary Injunction Patents, and its efforts to design around

2

them, are irrelevant to Apple’s Preliminary Injunction Motion.4 Samsung objects to Interrogatory Nos. 8-10 on the grounds that they are not limited to the Galaxy Nexus smartphone.5

B. Apple’s Motion to Compel Production of Documents Nos. 8, 16, 18, 21-22, 45, 48-50, 53-

55, 57, 59, 61-64, 67, 68, 70, 72, 74, 75, 77, 79, 81, and 91

On March 6, 2012, Apple served Samsung with 91 document requests in its First Set of Preliminary Injunction Requests for Production of Documents.6 Samsung responded on March 27, 2012, but refused to respond to the requests set forth in the subsection heading.7

Request Nos. 8, 21 and 22 seek documents that identify Samsung employees intimately involved with entering text in applications, Samsung’s discussions regarding the Android 4.0 Ice Cream Sandwich, and Samsung’s discussions with third-parties regarding the Galaxy Nexus.8 Samsung objects to these three requests, in relevant part, because they are not limited to the Galaxy Nexus and its four accused features.9

Request Nos. 16 and 18 seek documents regarding Samsung’s efforts to avoid infringing the Preliminary Injunction Patents, and documents relating to Android-supported Samsung products that also discuss the redesign of any Samsung product in light of Apple products.10 Samsung objects to Request No. 16 because copying is irrelevant to liability for patent

3

infringement, and to Request No. 18 because it does not relate to the Samsung Galaxy Nexus and the Preliminary Injunction Patents.11

Request Nos. 45, 48-50, 53-55, 57, 59, 61-64, 67, 68, 70, 72, 74, 75, 77, 79, and 81 seek, in relevant part, documents relating to the “sale of smartphones” and “competition between Apple and Samsung.”12 Samsung objects to these requests on the grounds that they seek documents regarding all Samsung smartphones and tablets, rather than documents cabined to the Galaxy Nexus.13 Request No. 91 seeks documents regarding instances of consumers confusing an Apple product for the Galaxy Nexus, or vice versa.14 Samsung objects to this request because consumer confusion is irrelevant to Apple’s Preliminary Injunction Motion—Samsung argues that the Galaxy Nexus may properly be compared to the Preliminary Injunction Patents only, and not to “the commercial embodiment of the patentee’s products.”15

C. Apple’s Motion to Compel Certain Discovery from Third-Party Google

Apple claims that after conferring with Samsung, Apple learned that certain responsive documents were in Google’s possession.16 Apple thereafter served Google with a subpoena dated April 5, 2012. The subpoena contains twelve requests.17

Requests Nos. 1 and 2 request a copy of the Android source code as provided to Samsung, and a copy of the source code as implemented by Samsung in the Galaxy Nexus.18 Request No. 3 seeks documents sufficient to show the difference between the Android code provided to Samsung,

4

and the publically available open source Android 4.0 Ice Cream Sandwich source code.19 Requests Nos. 4-12 seek documents regarding communications between Samsung and Google on the following topics: Android, Apple’s products, the accused features and their implementation, design-around efforts, analysis of Apple products, and consumer behavior regarding not only the accused features, but also searching the Internet on a mobile device.20 Apple also served Google with a Notice of Deposition on April 5, 2012.21 In it, Apple requested that Google make a 30(b)(6) witness available to testify concerning these twelve categories.22 Google objects to Apple’s requests to the extent Apple seeks documents or information beyond the functionalities accused in Apple’s Preliminary Injunction Motion.23

On May 3, 2012, Apple filed a Supplemental Declaration in Support of its Motion to Compel Discovery from third-party Google.24 In it, Apple claims Google failed to provide its source code expert with information sufficient to complete his analysis. Apple also claims Google failed to load software programs vital to its expert’s review on the machine that houses this code, as well as the publicly available version of the Android code. Google, in its May 4, 2012 response, argues that it has provided the source code pursuant to the terms of the protective order, and thus is in compliance with the court’s orders.25 Google also urges the court to deny Apple’s Request No. 3, which seeks documents sufficient to show the difference between the Android source code

5

provided to Samsung, and the publically available open source Android 4.0 Ice Cream Sandwich source code.26

II. LEGAL STANDARDS

Parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party's claim or defense. Relevant information need not be admissible at trial if the discovery appears reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence. The court must limit the frequency or extent of discovery if it is unreasonably cumulative or duplicative, or can be obtained from some other source that is more convenient, or the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit.27 Upon a showing of good cause, “the court may order discovery of any matter relevant to the subject matter involved in the action.”28

III. DISCUSSION

Apple’s Preliminary Injunction Motion seeks to halt Samsung from selling its Galaxy Nexus smartphone during the course of this litigation.29 Apple’s Motion accuses Samsung of infringing four Apple patents claiming “key” product features, which include “Slide to Unlock,” “Text Correction,” “Unified Search,” and “Special Text Detection.”30

At their heart, each of these discovery disputes, whether between Apple and Samsung, or Apple and Google, involves a fundamental disagreement over the scope of Preliminary Injunction discovery and the order by the presiding judge setting the briefing and hearing schedule for the Preliminary Injunction: “The parties may obtain discovery relevant to the preliminary injunction

6

motion. . . . The Court encourages the parties to make all efforts to keep discovery requests reasonable in scope and narrowly tailored to address the preliminary injunction motion.”31

Apple argues that inquiries outside of the Galaxy Nexus and its four accused features are nevertheless relevant to the Preliminary Injunction analysis. For example, Apple argues that if the accused features appeared earlier on a Samsung product, information about this earlier iteration of the feature is materially relevant to its cause, as is the same feature in an accused product. Apple also urges that a wider net is necessary to highlight for the court the systematic and widespread effort Samsung has made to copy Apple products. Samsung responds by highlighting the overwhelming burden that would be imposed by Apple’s demands.

Because the parties require a resolution to their dispute on an expedited basis, the court will keep its analysis brief. While Apple’s argument is conceptually appealing, Apple offers no basis upon which the court could reasonably limit Samsung’s burden. In other words, the court can think of no line it could draw, other than one focused on the accused features, that would respect the norms of proportionality applicable under Rule 26 even in a well-resourced, high-stakes case like this. Because Apple’s Preliminary Injunction Motion is targeted to Samsung’s Galaxy Nexus and the four accused features, Apple is entitled to take discovery on the four accused features as they are contained on that device. But to the extent Apple’s Preliminary Injunction discovery requests extend beyond the scope of the Galaxy Nexus smartphone and the four accused features, such discovery is properly left until after the Preliminary Injunction Motion is resolved.32

7

For the same reasons, Apple may take discovery from Google to the extent its requests address the Galaxy Nexus smartphone and the four accused features as they are implemented in that device. Google also shall make available for deposition the five declarants who submitted declarations supporting Samsung’s opposition to Apple’s Motion for a Preliminary Injunction who have not yet sat for deposition, as well as the 30(b)(6) witness Apple has requested. Google also shall produce to Apple documents relevant to each deposition at least 72 hours before the dates set for each witness’s deposition. Any witness who has already been deposed may be deposed again for three hours after the production of relevant documents. Google shall identify any Android version whose source code is produced to Apple with the specificity Apple requests in its papers, and shall load the publicly available version of the source code onto the same machine. Finally, Google shall load Cygwin and software with the ability to compare the relevant source code versions.

V. CONCLUSION

In accordance with the foregoing and subject to the limitations outlined above, the court GRANTS-IN-PART Apple’s motions to compel responses and production from Samsung, and GRANTS-IN-PART Apple’s motion to compel production and deposition testimony from Google. Samsung and Google shall comply with this order as follows: All interrogatory responses and documents shall be produced no later than May 6, 2012. All depositions shall take place no later than May 11, 2012.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Dated: 5/4/2012

[signature]

PAUL S. GREWAL

United States Magistrate Judge

________________

1 See Docket Nos. 1 (Compl.) and 10 (Mot. for Prelim. Inj.).

2 See Docket No. 96 (Apple Mot. to Compel) at 3.

3 See id.

4 See Docket No. 104 (Samsung Opp. to Mot. to Compel) at 1-2.

5 See id.

6 See Docket No. 99 (Apple Mot. to Compel) at 3.

7 Apple originally claimed that Samsung also failed to respond to Request No. 15. In its Opposition, Samsung claims that it changed its mind and produced documents responsive to Request No. 15. Apple’s Reply does not dispute this. The court therefore will not address this request.

8 See Docket No. 99 (Apple Mot. to Compel).

See Docket No. 103 (Samsung Opp. to Mot. to Compel) at 9-10.

10 See Docket No. 99 (Apple Mot. to Compel).

11 See id.

12 See Docket No. 103 (Samsung Opp. to Mot. to Compel) at 5.

13 See id. at 5-6.

14 See id. at 8.

15 See id.

16 See Docket No. 135 (Apple Mot. to Compel) at 1.

17 See id.

18 See id at 4.

19 See id.

20 See id.

21 See id.

22 See id. at 16-17.

23 See Docket No. 142 (Google Opp. to Mot. to Compel) at 1-3.

24 See Docket No. 155 (Supplemental Decl. in Support of Apple’s Motion).

25 See Docket No. 158 (Google’s Resp. to Supplemental Decl. in Support of Apple’s Motion) at 2.

26 See id. at 4.

27 See generally Fed. R. Civ. P. 26.

28 Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(1).

29 See Docket No. 10 (Apple Mot. for Prelim. Inj.).

30 See id.

31 Docket No. 37 (Order Setting Br’ing and Hr’ing Schedule) (emphasis added).

32 Apple cites no case law to support its assertion that all evidence of copying is rightfully within the scope of Preliminary Injunction discovery. Evidence of copying in general is therefore outside the scope of Preliminary Injunction discovery. At the same time, evidence of copying the four accused features contained in the Samsung Galaxy Nexus is properly within the scope of Preliminary Injunction discovery. Indeed, Samsung has already admitted as much. See Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Case No. C 11-1846 LHK (PSG), 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 110616, at *8 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 28, 2011) (“[W]illful infringement, including deliberate copying, may be relevant to a preliminary injunction motion . . . .”).

8

|

|

|

|

| Authored by: Anonymous on Sunday, September 02 2012 @ 05:50 PM EDT |

Sooner or later, there has to be case that makes the absurdity of software

patents so blindingly obvious that common sense returns to our legal

system. This case could well end with the invalidation of Apple's patents,

and maybe stir up consideration of the more general issue of granting

patents on mathematics.[ Reply to This | # ]

|

| |

| Authored by: rsteinmetz70112 on Sunday, September 02 2012 @ 05:56 PM EDT |

While I don't think Apple is right about this. Normally Apple, first would have