Prior

Art and Its Uses: A Primer

~ by Theodore C. McCullough*

Copyright

© 2006 Theodore C. McCullough

Licensed

under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 License

This article is also available as a PDF.

Overview The

question of what constitutes prior art can be confusing, to say the

least. Moreover, the issue of when one can and cannot use a

particular type of prior art in attacking the patentability of a

particular invention is equally confusing. The following is a

high-level outline of some of the key concepts regarding what

constitutes prior art, and how to apply it to address the

patentability of an invention. The purpose of this primer is not to

serve as formal legal advice, nor should it be considered as such.

Rather, the purpose of this primer is to assist the general public,

including those in the Open Source Community, with helping to improve

patent quality.

Types

of Prior Art

As a threshold matter, the definition of prior art hinges upon the notion of something that occurs before the filing date of a patent application. This "something" is typically the publication of a printed publication, or patent application, or patent, but, in some instances, can be evidence of the public use of an invention or the sale or offer of sale of an invention. In certain limited instances, prior inventorship can even serve as prior art. For the purpose of this primer, we are going to examine prior art as printed publications, patent applications or patents.

35

U.S.C 102 (A) & (B) Anticipation

Under 35 U.S.C. 102 et seq.

prior art is defined as a circumstance where:

(a) the invention was known or

used by others in this country, or patented or described in a printed

publication in this or a foreign country, before the invention

thereof by the applicant for patent: or

(b) the invention was patented

or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country or

in public use or on sale in this country, more than one year prior to

the date of the application for patent in the United States.

The key difference between anticipation under §§ (a) and (b) is that prior art arising under § (a) one can potentially defeat, whereas prior art under § (b) is next to impossible to defeat (i.e., it serves as a statutory bar to patentability). For example, if you have a printed prior art publication that was made available to the public more than a year before the filing date of the target patent (i.e., the patent you are seeking to invalidate), then you, as the patentee, cannot file an antedating affidavit arguing that your invention predates the prior-art reference. If, however, the printed publication was made available to the public within a year of filing, you can file an antedating affidavit to defeat the prior art. An additional difference between §§ (a) and (b) is that the former does not allow you to argue such things as evidence of a sale as a basis for arguing the invalidity of a patent.

35

US.C. 103(A) Obviousness

Under 35 U.S.C. 103(a) prior

art is described as a circumstance wherein:

(a) A patent may not be obtained though the invention is not identically disclosed or described as set forth in section 102 of this title, if the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains. Patentability shall not be negatived by the manner in which the invention was made.

In order to make a showing of obviousness, a prima facie case of obviousness must be shown. To establish a prima facie case of obviousness, three basic criteria must be met. First, there must be some suggestion or motivation, either in the prior-art references themselves or in the knowledge generally available to one of ordinary skill in the art, to modify the prior-art references or to combine reference teachings. Second, there must be a reasonable expectation of success. Finally, the prior art reference (or references when combined) must teach or suggest all the claim limitations. The teaching or suggestion to make the claimed combination and the reasonable expectation of success must both be found in the prior art, and not based on applicant's disclosure.

Explaining

Anticipation versus Obviousness

The primary difference between anticipation and obviousness is described as follows. If you have a single printed publication, patent application, or patent that enables you to practice (i.e., prior-art reference tells you how to build it, and/or someone knowledgeable in the art would know how to build it) the claimed technology disclosed in the target patent (i.e., the patent you are seeking to invalidate), then you argue anticipation. However, if you have more than one printed publication, patent application, or patent that collectively (not individually) enable to you practice the claimed technology disclosed in the target patent, then you argue obviousness. Relative to anticipation, obviousness is a harder legal concept to argue because during the course of arguing that the more than one reference invalidates the target patent, you must prove that a suggestion or motivation to combine the multiple references exists. This suggestion or motivation to combine can be provided by the references themselves, through another document, or, in some instances, though affidavit or declaration testimony by one knowledgeable in the art. Absent providing such a suggestion or motivation to combine, the patentee can attack the basis for arguing obviousness (i.e., attack the prima facie case of obviousness).

The difference between anticipation and obviousness can be further understood in the following example. If you have a target patent that claims elements a, b, c and d, then your single printed prior art reference must disclose and enable elements a, b, c, and d in order to anticipate the claims of the target patent. If, for example, however, you have both a diagram that discloses using elements a, b, c, and d together, but does not enable these elements, and additional separate printed prior art references that individually disclose how to make and use (i.e, enable) a, b, c, and d, then the diagram would serve as the suggestion or motivation to combine the separate printed prior art references

for the purpose of arguing obviousness.

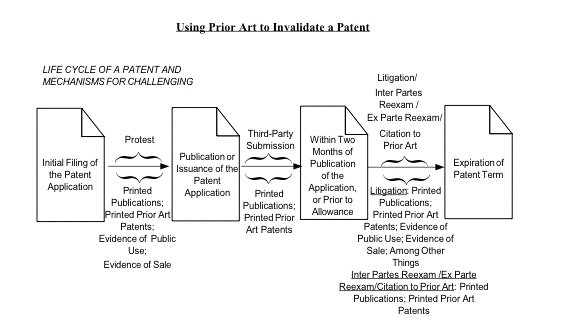

Using

Prior Art to Invalidate a Patent

Protest

If

you want to cite prior art against a patent application before it is

published, then you can file a Protest. The advantage of a Protest is that you can use, among others

things, prior art including evidence of public use and sales. The disadvantage is that it is very unlikely that one will learn of

a patent prior to its publication as a patent application. However,

in those instances where one does learn of a patent application that

has been filed, a Protest is a very powerful weapon.

Third-Party

Submissions

If

you want to target a patent application after it has published, but

before it issues as as patent, then you can file a Third-Party

Submission.

The advantage of a Third-Party Submission is that presently it is the only mechanism that allows one to attack the validity of a pending printed patent application. The disadvantage of this mechanism is that, different than all the other ways to challenge the validity of a patent, you cannot direct the patent examiner's attention to specific arguments as to how the prior art anticipates or renders obvious the technology at issue. Of note, you can, however, redact non-relevant portions of the Third-Party Submission, in effect, directing the examiner's attention, but one still cannot comment on the submitted prior art.

The filing cost for a Third-Party Submission is $180.

Litigation

If

you want to target a patent application after it has issued as a

patent, then, assuming you have standing , you can sue. The advantage

of suing to invalidate a patent, through, for example, bringing a

declaratory judgment action, is that you can argue most anything

under the sun to invalidate the patent including 35 U.S.C.

§§ 102 et seq., 103(a), 112 et seq., and inequitable conduct on the part

of the patentee in prosecuting the patent. The disadvantage is the

cost of litigation, and the fact that you will have to overcome the

presumption of validity that an issued patent enjoys.

A patent undergoing, for example, Reexam (see below)

does not enjoy this presumption of validity.

Reexamination

Again,

if you want to target a patent application after it has issued as a

patent, then you can file for a Reexam. Reexam comes in two flavors:

Ex Parte Reexam and Inter Partes Reexam.

Both are limited to prior-art submissions in the form of printed

publications, patent applications, and patents.

The difference between the two types of Reexam is that the Ex Parte Reexam is, more or less, a one-shot deal where you file your reexam request in the form of printed prior art, patent, or patent application and hope that the examiner agrees with what you argue without the need of additional comments or arguments. Inter Partes Reexam, on the other hand, is more or less like administrative litigation wherein you, as the third-party requester, have the right of appeal all the way up to the Federal Courts if necessary. The cost for filing an Ex Parte Reexam is $2520, while the

filing cost for Inter Partes Reexam is $8800.

Citation

to Prior Art

And

again, if you want to target a patent application after it has issued

as a patent, then you can file a Citation to Prior Art.

A Citation to Prior Art is known as the "poor man's reexam", in that it costs nothing to file. As with Third-Party Submissions, and the two flavors of Reexam, Citations to Prior Art are limited to printed publications and patents. The advantage of a Citation to Prior Art is the fact that it costs nothing to file. The disadvantage is that it does nothing by itself to invalidate the

target patent; rather, the party filing the Citation to Prior Art

must rely on the patentee to file a reexam to get the cited art in

front of an examiner.

Future

Prior Art Uses

Peer to Patent Project One project that is in a pilot stage is the "Peer to Patent" project, wherein the general public will be allowed to comment and provide prior art in the form of printed publications and patents on pending patent applications via an online mechanism. The project was founded by Professor Beth Noveck at New York University School of Law and is supported by members of the Open Source community and the United States Patent and Trademark Office among others. In terms of the above discussion, this online comment mechanism would supplement the Third-Party Submissions described above, and, in effect, is a type of online Third-Party Submission.

Open Source as Prior Art Project

Different than the various mechanisms described above by which a third party can seek to ensure patent quality, the Open Source as Prior Art Project allows patent examiners a way to ensure patent quality by providing them with a way to review technology developed by the Open Source Community. The project will allow the patent examiners the ability to access open source software -- with its millions of lines of publicly available computer source code contributed by thousands of programmers -- as potential prior art against patent applications. OSDL, IBM, Novell, Red Hat and VA Software's SourceForge.net will develop a system that stores source code in an electronically searchable format, satisfying legal requirements to qualify as prior art. Information for this project is available on the Open Source Development Labs' web site.

Patent Quality Index Initiative

Another initiative to ensure patent quality is the Patent Quality Index Initiative. This initiative will create a unified, numeric index to assess the quality of patents and patent applications. The effort will be directed by Professor R. Polk Wagner of the University of Pennsylvania and will be an open, public resource for the patent system. The index will be constructed with extensive community input, backed by statistical research and will become a dynamic, evolving tool with broad applicability for inventors, participants in the marketplace and the USPTO.

Conclusion

Prior art is typically a printed publication, patent, or patent application that has a publication or filing date prior to the filing date of the target patent. There are a variety of mechanisms/legal regimes that can be used to apply this prior art to invalidate a target patent. These mechanisms include: Protest, Third-Party Submission, Litigation, Reexam, and Citation to Prior Art. In addition to these existing mechanism, various projects and initiative relating to the use of prior art are under way. The purpose of these mechanisms, projects and initiatives is to ensure that true innovation is protected.

* Author: Theodore C. McCullough, Registered Patent Attorney, tmccullough at lpatent.com.

1

Note that a printed publication must have been made available to the public, in addition to being printed. (See Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (“MPEP”) §2128).

2 See, MPEP § 715 ("Affidavits or declarations under 37 CFR § 1.131 may be used, for example: (A) To antedate a reference or activity that qualifies as prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a) and not under 35 U.S.C. § 102(b), e.g., where the prior art date under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a) of the patent, the publication or activity used to reject the claim(s) is less than 1 year prior to applicant's or patent owner's effective filing date.").

3 See MPEP § 2142. See generally MPEP § 2143.

4 See e.g., (EDAT Brochure, Pg. 3.).

5 See MPEP § 1904.01 (“Except where a protest is accompanied by the

written consent of the applicant as provided in 37 CFR §

1.291(b)(1), a protest under 37 CFR § 1.291(a) must be

submitted prior to the date the application was published under 37

CFR § 1.211 or the mailing of a notice of allowance under 37

CFR § 1.311, whichever occurs first, and the application must

be pending when the protest and application file are brought before

the examiner in order to be ensured of consideration.”) (emphasis added).

6

See

MPEP § 1901.02 ("(A) Information demonstrating that the invention was publicly "known or used by others in this country... before the invention thereof by the applicant for patent" and is therefore barred under 35 U.S.C. §§ 102(a) and/or 103. (B) Information that the invention was "in public use or on sale in this country, more than 1 year prior to the date of the application for patent in the United States" ( 35 U.S.C. § 102(b)). (C) Information that the applicant "has abandoned the invention" ( 35 U.S.C. § 102(c)) or "did not himself invent the subject matter sought to be patented" ( 35 U.S.C. § 102(f)). (D) Information relating to inventorship under 35 U.S.C. § 102(g). (E) Information relating to sufficiency of disclosure or failure to disclose best mode, under 35 U.S.C. § 112. (F) Any other information demonstrating that the application lacks compliance with the statutory requirements for patentability. (G) Information indicating "fraud" or "violation of the duty of disclosure" under 37 CFR § 1.56 may be the subject of a protest under 37 CFR § 1.291. Protests raising fraud or other inequitable conduct issues will be entered in the application file, generally without comment on those issues. 37 CFR § 1.291".).

7 It should be noted that a Protest can also be used to apply prior art against a patent under reissue, and in such a circumstance has great practical usefulness due to the breath of what is considered prior art in a Protest. See MPEP 1901.03.

8 See 37 C.F.R. § 1.99(a) ("(a) A submission by a member of the public of patents or publications relevant to a pending published application may be entered in the application file if the submission complies with the requirements of this section and the application is still pending when the submission and application file are brought before the examiner. (b) A submission under this section must identify the application to which it is directed by application number and include: (1) The fee set forth in § 1.17(p); (2) A list of the patents or publications submitted for consideration by the Office, including the date of publication of each patent or publication; (3) A copy of each listed patent or publication in written form or at least the pertinent portions; and (4) An English language translation of all the necessary and pertinent parts of any non-English language patent or publication in written form relied upon. (c) The submission under this section must be served upon the applicant in accordance with § 1.248. (d) A submission under this section shall not include any explanation of the patents or publications, or any other information. The Office will not enter such explanation or information if included in a submission under this section..") There are certain timelines governing a third-party submission. (See MPEP § 1134.01 ("37 CFR § 1.99(e) specifies that a submission under 37 CFR § 1.99 must be filed within two months from the date of publication of the application (37 CFR § 1.215(a)), or prior to the mailing of a notice of allowance (37 CFR § 1.311), whichever is earlier. Republication of an application under 37 CFR § 1.221 does not restart the two-month period specified in 37 CFR § 1.99(e).") (emphasis added).

9 See id. (“The third party may, however, submit redacted versions of a

patent or publication containing only the most relevant portions of

the patent or publication.”).

10 Different than the other four (4) mechanisms (i.e., Protests, Third-Party Submission, Reexam, and Citation to Prior Art) which can be used by any member of the general public (see e.g., MPEP 1901.01 ("Any member of the public, including private persons, corporate entities, and government agencies, may file a protest under 37 CFR 1.291."); MPEP 1134.01 ("A submission by a member of the public of patents or publications relevant to a pending published application may be entered in the application file "); MPEP 2212 ("any person may file a request for reexamination of a patent "); MPEP 2203 ("The patent owner, or any member of the public, may submit prior art citations of patents or printed publications ").), to file suit to invalidate a patent (i.e., bring a declaratory judgment action) you must have standing to sue. Standing requires, among other things, that an actual case or controversy exist between parties. (See e.g., Microchip Technology v. The Chamberlain Group, (Dkt#05-1339) (Fed. Cir. 2006) (standing to bring a declaratory judgment action requires: 1) a reasonable apprehension on the part of the plaintiff that it will face a patent infringement suit if it commences or continues with the activity at issue, and 2) the present activity by the declaratory plaintiff would constitute infringement, or concrete steps are taken by the plaintiff with intent to conduct such infringing activity).).

11

See

35 U.S.C. § 282 ("A patent shall be presumed valid. Each claim of a patent (whether in independent, dependent, or multiple dependent form) shall be presumed valid independently of the validity of other claims; dependent or multiple dependent claims shall be presumed valid even though dependent upon an invalid claim. . . The burden of establishing invalidity of a patent or any claim thereof shall rest on the party asserting such invalidity.").

12

See MPEP § 2211 ("Under 37 CFR § 1.510(a), any person may, at any time during the period of enforceability of a patent, file a request for ex parte reexamination."); MPEP § 2611 ("An inter partes reexamination can be filed for a patent issued from an original application filed on or after November 29, 1999.") (emphasis added).

13

See

MPEP § 2214 and § 2614.

14 See

e.g.http://www.eff.org/patent/wanted/test/testcom_reexam.pdf (providing an example of an Ex Parte Reexam request).

15 See

e.g.http://www.eff.org/patent/wanted/clearchannel/CC_reexam.pdf (providing an example of an Inter Partes Reexam request).

16 See MPEP § 2202 (“Any person at any time may cite to the Office

in writing prior art consisting of patents or printed publications

which that person believes to have a bearing on the patentability of

any claim of a particular patent.”) .

17 See MPEP § 2205.

18 A patentee can file a Reexam against their own patent. (See MPEP 2212(a).) One purpose of such a move on the part of the patentee is to get newly discovered prior art in front of an examiner and have the examiner make a determination that this newly discovered art does not affect the breadth of their claims. Once such a determination is made, then a potential adversary (e.g., a defendant in a patent infringement suit) will be hard pressed to use this same prior art against the patent, given that an examiner has already made a determination that the prior art does not affect claim breadth.

19

See

http://dotank.nyls.edu/communitypatent/

20 See http://developer.osdl.org/dev/priorart/.

21 See http://www.patentqualityindex.org; http://www.groklaw.net/article.php?story=2006011009141979.

|